Becca Rothfeld at The Hedgehog Review:

Graduate school is psychologically punishing for people in every field, not just for people who worry that their topic is especially ineffectual. The more you read, the more you realize you should have read already. But philosophy’s claim to despair is unique. As Stanley Cavell writes in the introduction to Must We Mean What We Say?, “It is characteristic of philosophy that from time to time it appear—that from time to time it be—irrelevant to one’s concerns…. just as it is characteristic that from time to time it be inescapable.”1 In other words, it is not just the current conditions of economic precarity that render philosophy alternately irrelevant and inescapable—or, peculiarly and more often than not, irrelevant and inescapable at once. David Hume lived two centuries before the horrors of the academic job market kicked into high gear, but that did not stop him from worrying that his philosophical musings remained remote from real life. At the end of Book I of A Treatise of Human Nature (1738), he paused to reflect that the skeptical concerns he had just spent a hundred pages developing were wont to dissipate as soon as he headed to the pub:

Graduate school is psychologically punishing for people in every field, not just for people who worry that their topic is especially ineffectual. The more you read, the more you realize you should have read already. But philosophy’s claim to despair is unique. As Stanley Cavell writes in the introduction to Must We Mean What We Say?, “It is characteristic of philosophy that from time to time it appear—that from time to time it be—irrelevant to one’s concerns…. just as it is characteristic that from time to time it be inescapable.”1 In other words, it is not just the current conditions of economic precarity that render philosophy alternately irrelevant and inescapable—or, peculiarly and more often than not, irrelevant and inescapable at once. David Hume lived two centuries before the horrors of the academic job market kicked into high gear, but that did not stop him from worrying that his philosophical musings remained remote from real life. At the end of Book I of A Treatise of Human Nature (1738), he paused to reflect that the skeptical concerns he had just spent a hundred pages developing were wont to dissipate as soon as he headed to the pub:

I dine, I play a game of back-gammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends; and when after three or four hours’ amusement, I wou’d return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strain’d, and ridiculous, that I cannot find in my heart to enter into them any farther.2

more here.

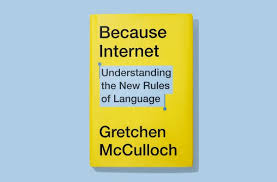

What is the language of the internet? Most of us have probably heard of LOL (or lol), omg, emojis and even memes, and come face to face with unconventional confections of exclamation marks, repeated letters and novelty punctuation. For people like us, top-end book lovers, the language of the internet might seem, well, rather ghastly: illiterate, limited, debased, invasive like Japanese knotweed, a frightful triffid threatening to obliterate decent standards of communication. They, the internet lovers, if they even bother to glance in our direction, will think: omg!!!!11!!! sad lol.

What is the language of the internet? Most of us have probably heard of LOL (or lol), omg, emojis and even memes, and come face to face with unconventional confections of exclamation marks, repeated letters and novelty punctuation. For people like us, top-end book lovers, the language of the internet might seem, well, rather ghastly: illiterate, limited, debased, invasive like Japanese knotweed, a frightful triffid threatening to obliterate decent standards of communication. They, the internet lovers, if they even bother to glance in our direction, will think: omg!!!!11!!! sad lol. Maya Angelou published the first of her seven memoirs not long after she distinguished herself as the star raconteur at a dinner party. “At the time, I was really only concerned with poetry, though I had written a television series,” she would recall. James Baldwin, the novelist and activist, took her to the party, which was at the home of the cartoonist-writer Jules Feiffer and his then-wife, Judy. “We enjoyed each other immensely and sat up until 3 or 4 in the morning, drinking Scotch and telling tales,” Angelou went on. “The next morning, Judy Feiffer called a friend of hers at Random House and said, ‘You know the poet Maya Angelou? If you could get her to write a book…’” That book became

Maya Angelou published the first of her seven memoirs not long after she distinguished herself as the star raconteur at a dinner party. “At the time, I was really only concerned with poetry, though I had written a television series,” she would recall. James Baldwin, the novelist and activist, took her to the party, which was at the home of the cartoonist-writer Jules Feiffer and his then-wife, Judy. “We enjoyed each other immensely and sat up until 3 or 4 in the morning, drinking Scotch and telling tales,” Angelou went on. “The next morning, Judy Feiffer called a friend of hers at Random House and said, ‘You know the poet Maya Angelou? If you could get her to write a book…’” That book became  Nabokov, who made ends meet by giving boxing lessons, assured his genteel audience there was nothing frightful in the violent punches: “I hasten to add that in such a blow, which brings on an instantaneous blackout there is nothing terrible. On the contrary. I have experienced it myself, and can attest that such a sleep is rather pleasant.”

Nabokov, who made ends meet by giving boxing lessons, assured his genteel audience there was nothing frightful in the violent punches: “I hasten to add that in such a blow, which brings on an instantaneous blackout there is nothing terrible. On the contrary. I have experienced it myself, and can attest that such a sleep is rather pleasant.” Toward the end of the Stone Age, in a small fishing village in southern Denmark, a dark-skinned woman with brown hair and piercing blue eyes chewed on a sticky piece of hardened birch tar. The village, dubbed Syltholm by modern archaeologists, was near a coastal lagoon that was protected from the Baltic Sea by sandy barrier islands. Behind them, the woman and her kin built weirs to trap fish that they skewered with bone-tipped spears. The woman may have worked the tar until it was pliable enough to repair a piece of pottery or a polished flint tool—birch tar was a common Stone Age adhesive. Or she might have simply been enjoying what amounted to Neolithic chewing gum. In any case, when she discarded the tar, it was sealed away under layers of sand and silt for some 5,700 years until a team of archaeologists found it. Amazingly, they were able to extract the woman’s complete genome from the birch tar, along with her oral microbiome and DNA from food she may have recently eaten.

Toward the end of the Stone Age, in a small fishing village in southern Denmark, a dark-skinned woman with brown hair and piercing blue eyes chewed on a sticky piece of hardened birch tar. The village, dubbed Syltholm by modern archaeologists, was near a coastal lagoon that was protected from the Baltic Sea by sandy barrier islands. Behind them, the woman and her kin built weirs to trap fish that they skewered with bone-tipped spears. The woman may have worked the tar until it was pliable enough to repair a piece of pottery or a polished flint tool—birch tar was a common Stone Age adhesive. Or she might have simply been enjoying what amounted to Neolithic chewing gum. In any case, when she discarded the tar, it was sealed away under layers of sand and silt for some 5,700 years until a team of archaeologists found it. Amazingly, they were able to extract the woman’s complete genome from the birch tar, along with her oral microbiome and DNA from food she may have recently eaten. Bank robber Willie Sutton famously said that banks were “where the money is,” and the money available for politics in 1992 had moved from the pockets of working people (

Bank robber Willie Sutton famously said that banks were “where the money is,” and the money available for politics in 1992 had moved from the pockets of working people ( At full capacity, these companies expect to dredge thousands of square miles a year. Their collection vehicles will creep across the bottom in systematic rows, scraping through the top five inches of the ocean floor. Ships above will draw thousands of pounds of sediment through a hose to the surface, remove the metallic objects, known as polymetallic nodules, and then flush the rest back into the water. Some of that slurry will contain toxins such as mercury and lead, which could poison the surrounding ocean for hundreds of miles. The rest will drift in the current until it settles in nearby ecosystems. An early study by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences predicted that each mining ship will release about 2 million cubic feet of discharge every day, enough to fill a freight train that is 16 miles long. The authors called this “a conservative estimate,” since other projections had been three times as high. By any measure, they concluded, “a very large area will be blanketed by sediment to such an extent that many animals will not be able to cope with the impact and whole communities will be severely affected by the loss of individuals and species.”

At full capacity, these companies expect to dredge thousands of square miles a year. Their collection vehicles will creep across the bottom in systematic rows, scraping through the top five inches of the ocean floor. Ships above will draw thousands of pounds of sediment through a hose to the surface, remove the metallic objects, known as polymetallic nodules, and then flush the rest back into the water. Some of that slurry will contain toxins such as mercury and lead, which could poison the surrounding ocean for hundreds of miles. The rest will drift in the current until it settles in nearby ecosystems. An early study by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences predicted that each mining ship will release about 2 million cubic feet of discharge every day, enough to fill a freight train that is 16 miles long. The authors called this “a conservative estimate,” since other projections had been three times as high. By any measure, they concluded, “a very large area will be blanketed by sediment to such an extent that many animals will not be able to cope with the impact and whole communities will be severely affected by the loss of individuals and species.” Lung cancer, rampant. No surprise. I’ve smoked since I was sixteen, behind the high-school football bleachers in Northfield, Minnesota. I used to fear the embarrassment of dying youngish, letting people natter sagely, “He smoked, you know.” But at seventy-seven I’m into the actuarial zone.

Lung cancer, rampant. No surprise. I’ve smoked since I was sixteen, behind the high-school football bleachers in Northfield, Minnesota. I used to fear the embarrassment of dying youngish, letting people natter sagely, “He smoked, you know.” But at seventy-seven I’m into the actuarial zone. One great thing about Harry in Blondie was exactly this tension: she could look and sound so sweet and doll-like, but she was obviously and unapologetically a woman with a past. Another was the dynamic she had, so pale and starry, with her dark-haired, bridge-and-tunnelly band. Her outfits helped too, weird shapes and garish colours in nasty synthetic fabrics that looked like they came – and from what the book says, probably did – from a bargain bin in the Bowery: the big shirt that kept falling off the shoulder, what with all the awkward dancing; the harsh turquoise suit and shirt and tie; the ripply grey one-armed chiffon, worn with mules and thick black tights. The hair kept changing, though it was always blonde and afloat with static, stripped and dyed within an inch of its life. Sometimes it was big and thick and exhausting-looking. Sometimes it was shorter and lighter, in a bob. Usually you saw roots, a thick black skunk-stripe even. ‘Being a bleached blonde for so many years,’ Harry writes, ‘has made me acutely aware of what healthy hair looks like.’ There’s a picture in the book of a family Christmas in New Jersey, with her hair in its undyed colour, a plain, flat

One great thing about Harry in Blondie was exactly this tension: she could look and sound so sweet and doll-like, but she was obviously and unapologetically a woman with a past. Another was the dynamic she had, so pale and starry, with her dark-haired, bridge-and-tunnelly band. Her outfits helped too, weird shapes and garish colours in nasty synthetic fabrics that looked like they came – and from what the book says, probably did – from a bargain bin in the Bowery: the big shirt that kept falling off the shoulder, what with all the awkward dancing; the harsh turquoise suit and shirt and tie; the ripply grey one-armed chiffon, worn with mules and thick black tights. The hair kept changing, though it was always blonde and afloat with static, stripped and dyed within an inch of its life. Sometimes it was big and thick and exhausting-looking. Sometimes it was shorter and lighter, in a bob. Usually you saw roots, a thick black skunk-stripe even. ‘Being a bleached blonde for so many years,’ Harry writes, ‘has made me acutely aware of what healthy hair looks like.’ There’s a picture in the book of a family Christmas in New Jersey, with her hair in its undyed colour, a plain, flat The study of memory has always been one of the stranger outposts of science. In the 1950s, an unknown psychology professor at the University of Michigan named James McConnell made headlines—and eventually became something of a

The study of memory has always been one of the stranger outposts of science. In the 1950s, an unknown psychology professor at the University of Michigan named James McConnell made headlines—and eventually became something of a  Artificial intelligence (AI) technology developed by the RIKEN Center for Advanced Intelligence Project (AIP) in Japan has successfully found features in pathology images from human cancer patients, without annotation, that could be understood by human doctors. Further, the AI identified features relevant to cancer prognosis that were not previously noted by pathologists, leading to a higher accuracy of prostate cancer recurrence compared to pathologist-based diagnosis. Combining the predictions made by the AI with predictions by human pathologists led to an even greater accuracy. According to Yoichiro Yamamoto, the first author of the study published in Nature Communications, “This technology could contribute to personalized medicine by making highly accurate prediction of

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology developed by the RIKEN Center for Advanced Intelligence Project (AIP) in Japan has successfully found features in pathology images from human cancer patients, without annotation, that could be understood by human doctors. Further, the AI identified features relevant to cancer prognosis that were not previously noted by pathologists, leading to a higher accuracy of prostate cancer recurrence compared to pathologist-based diagnosis. Combining the predictions made by the AI with predictions by human pathologists led to an even greater accuracy. According to Yoichiro Yamamoto, the first author of the study published in Nature Communications, “This technology could contribute to personalized medicine by making highly accurate prediction of  Dad called us, Thom and me, into the office. Its bifold louvre doors opened just behind my dining chair. He showed us the safe deposit key again. He showed us his will again. He showed us the folders of information about the condo in Florida, about his car, the binders of account statements, his credit cards, his social security, pension, and insurance policies. Part of me resisted.

Dad called us, Thom and me, into the office. Its bifold louvre doors opened just behind my dining chair. He showed us the safe deposit key again. He showed us his will again. He showed us the folders of information about the condo in Florida, about his car, the binders of account statements, his credit cards, his social security, pension, and insurance policies. Part of me resisted. In the United States,

In the United States,  The numbers of people dying, week in, week out, tell us more about the four countries of the UK than we could ever hope to learn from the attention given to Brexit. This is a kingdom falling apart.

The numbers of people dying, week in, week out, tell us more about the four countries of the UK than we could ever hope to learn from the attention given to Brexit. This is a kingdom falling apart. As the title indicates, this is a book about liberalism and The Economist’s propagation of it. But as the great Professor Joad would have said, ‘It all depends what you mean by liberalism.’ These days there is much talk of the differences between political liberalism, economic liberalism and social liberalism. In the 19th century, when The Economist was establishing its reputation, its commitment to free trade and capitalism was such that, with regard to the humanitarian 1844 Factory Act, it could opine: ‘the more it is investigated, the more we are compelled to acknowledge that in any interference with industry and capital, the law is powerful only for evil, but utterly powerless for good.’

As the title indicates, this is a book about liberalism and The Economist’s propagation of it. But as the great Professor Joad would have said, ‘It all depends what you mean by liberalism.’ These days there is much talk of the differences between political liberalism, economic liberalism and social liberalism. In the 19th century, when The Economist was establishing its reputation, its commitment to free trade and capitalism was such that, with regard to the humanitarian 1844 Factory Act, it could opine: ‘the more it is investigated, the more we are compelled to acknowledge that in any interference with industry and capital, the law is powerful only for evil, but utterly powerless for good.’ Godsmack is part of an aggressive, no-cowards-allowed milieu of hard rock known as “post-grunge” (or pejoratively “butt rock”), which was at its most lucrative during the late 1990s and throughout the aughts, when it dominated both the rock and pop charts. Obscuring the stylistic boundaries between neighboring genres—country, grunge, and the genre which grunge supposedly killed, hair metal—post-grunge is characterized by its dragging tempos, down-tuned chord progressions, sporadic twanginess, and overly passionate vocals. If you took an eighties power ballad’s major key and turned it minor, you’d have a post-grunge song more or less. Even today, as its pop appeal has vanished, it remains viable in the realm of mainstream rock, selling out amphitheaters and filling up the playlists on “Alt Nation”-type stations. It soundtracks WWE pay-per-views; it’s what plays over the loudspeakers in Six Flags food courts.

Godsmack is part of an aggressive, no-cowards-allowed milieu of hard rock known as “post-grunge” (or pejoratively “butt rock”), which was at its most lucrative during the late 1990s and throughout the aughts, when it dominated both the rock and pop charts. Obscuring the stylistic boundaries between neighboring genres—country, grunge, and the genre which grunge supposedly killed, hair metal—post-grunge is characterized by its dragging tempos, down-tuned chord progressions, sporadic twanginess, and overly passionate vocals. If you took an eighties power ballad’s major key and turned it minor, you’d have a post-grunge song more or less. Even today, as its pop appeal has vanished, it remains viable in the realm of mainstream rock, selling out amphitheaters and filling up the playlists on “Alt Nation”-type stations. It soundtracks WWE pay-per-views; it’s what plays over the loudspeakers in Six Flags food courts. It is unusual to find a writer of 88 embarking on a dramatic change of style and taking pains to justify it, but O’Brien still cares what people think. The week we met, she’d won the David Cohen Prize for Literature, a major recognition of a lifetime’s work which has, for other winners, been followed by a Nobel Prize. But she is still stung by a New Yorker profile from October in which, over the course of 10,000 words, the staff writer Ian Parker took the decision to put under the microscope the colourful, heightened way she has told her life story. O’Brien remembered a preacher denouncing the provocative (some said “filthy”) The Country Girls in the pulpit of the church near her home in Tuamgraney, then burning it: Parker said no one in the village recalled the same. And her relationship with her mother may not have been as hostile as she’s made out, he suggested – Lena O’Brien speaks affectionately in much of their correspondence…

It is unusual to find a writer of 88 embarking on a dramatic change of style and taking pains to justify it, but O’Brien still cares what people think. The week we met, she’d won the David Cohen Prize for Literature, a major recognition of a lifetime’s work which has, for other winners, been followed by a Nobel Prize. But she is still stung by a New Yorker profile from October in which, over the course of 10,000 words, the staff writer Ian Parker took the decision to put under the microscope the colourful, heightened way she has told her life story. O’Brien remembered a preacher denouncing the provocative (some said “filthy”) The Country Girls in the pulpit of the church near her home in Tuamgraney, then burning it: Parker said no one in the village recalled the same. And her relationship with her mother may not have been as hostile as she’s made out, he suggested – Lena O’Brien speaks affectionately in much of their correspondence…