“Many American men…do not have enough awakened or living warriors

inside to defend their soul houses.” —Robert Bly

Old Self

I chanced across my old self

today. He was sitting in the second

floor office where I used to work —

at the typewriter, young, thin guy,

in his late twenties, white shirt, narrow

dark tie, serious demeanor, writing

an essay against the Viet Nam war.

I came up the stairs and saw him —

a decent human being, diligent,

not remotely aware of the ambush

life had waiting — not knowing

he’d permit himself to be taken

prisoner and then, in confusion,

do desperate things, betray

what he loved — and that nothing

would enable him to survive

as he was.

I passed the open door

and wanted to cry out — warn him,

force the warriors to raise

their spears. But even hearing

my shout, he would have only

hesitated, then turned back to

his devoted, lonely and interminable

work.

by Lou Lipsitz

from Seeking the Hook

Signal Books, 1997

In 1831, Alexis de Tocqueville took a 10-month trip to the United States to study the American penal system. In the resulting book—

In 1831, Alexis de Tocqueville took a 10-month trip to the United States to study the American penal system. In the resulting book— The Greek statesman Demosthenes is credited with saying “I am a citizen of the world,” and the idea that we should take a cosmopolitan view of our common humanity is a compelling one. Not everyone agrees, however; in the words of former British Prime Minister Theresa May, “If you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere.” On the other side of the political spectrum, groups who share a feature of identity — race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and others — find it useful to band together to make political progress. Kwame Anthony Appiah is a leading philosopher and cultural theorist who has thought carefully about the tricky issues of cosmopolitanism and identity. We talk about how identities form, why they matter, and how to negotiate the difficult balance between being human and being your particular self.

The Greek statesman Demosthenes is credited with saying “I am a citizen of the world,” and the idea that we should take a cosmopolitan view of our common humanity is a compelling one. Not everyone agrees, however; in the words of former British Prime Minister Theresa May, “If you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere.” On the other side of the political spectrum, groups who share a feature of identity — race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and others — find it useful to band together to make political progress. Kwame Anthony Appiah is a leading philosopher and cultural theorist who has thought carefully about the tricky issues of cosmopolitanism and identity. We talk about how identities form, why they matter, and how to negotiate the difficult balance between being human and being your particular self. You should sit low, not on a chair or a stool or a couch. A small crate will do the job. Or anything that is lower than 9.5 inches from the ground. You can’t shave or cut your hair. You can’t have sex. You shouldn’t take a shower, though you may do some light swabbing of your especially funky bits, as well as dousing your feet and hands in cold water now and again. You can’t greet people in the normal way. You definitely cannot work. No freshly laundered clothes. The list of things you cannot do is long.

You should sit low, not on a chair or a stool or a couch. A small crate will do the job. Or anything that is lower than 9.5 inches from the ground. You can’t shave or cut your hair. You can’t have sex. You shouldn’t take a shower, though you may do some light swabbing of your especially funky bits, as well as dousing your feet and hands in cold water now and again. You can’t greet people in the normal way. You definitely cannot work. No freshly laundered clothes. The list of things you cannot do is long. GEORGE STEINER IS A CHARMING

GEORGE STEINER IS A CHARMING Men not reading women’s writing is widespread, and they begin not reading early. In the university applications that cross my desk, it’s common for male candidates not to mention a single female author, despite otherwise showing evidence of wide and ambitious reading. The opposite is rare.

Men not reading women’s writing is widespread, and they begin not reading early. In the university applications that cross my desk, it’s common for male candidates not to mention a single female author, despite otherwise showing evidence of wide and ambitious reading. The opposite is rare. “I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman,” wrote Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own (1929). In that essay, commenting on the fact that women’s lives are “all but absent from history,” she argues that this is not only a consequence of the ways women have been deprived of the material conditions under which their talents can prosper but also reveals the sort of events and lives historians have traditionally considered worth remembering—primarily, the public activities of “great men.” Perusing the index of G. M. Trevelyan’s History of England, Woolf looks up “position of women” and is dismayed to find only a smattering of references, mostly to customs of arranged marriage, wife-beating, and the fictional heroines of Shakespeare. Flicking through chapters on wars and kings, she wonders why so little room is left for women’s activities in the events that “constitute this historian’s view of the past.” It was clear to Woolf that new histories were needed, which would examine the reality of women’s lives, their relationships and activities, and the forces that thwarted their ambitions.

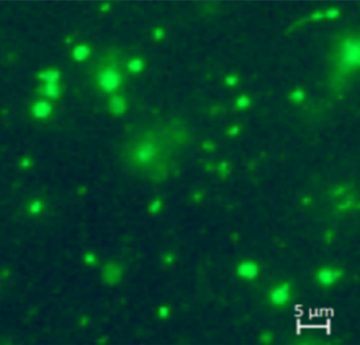

“I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman,” wrote Virginia Woolf in A Room of One’s Own (1929). In that essay, commenting on the fact that women’s lives are “all but absent from history,” she argues that this is not only a consequence of the ways women have been deprived of the material conditions under which their talents can prosper but also reveals the sort of events and lives historians have traditionally considered worth remembering—primarily, the public activities of “great men.” Perusing the index of G. M. Trevelyan’s History of England, Woolf looks up “position of women” and is dismayed to find only a smattering of references, mostly to customs of arranged marriage, wife-beating, and the fictional heroines of Shakespeare. Flicking through chapters on wars and kings, she wonders why so little room is left for women’s activities in the events that “constitute this historian’s view of the past.” It was clear to Woolf that new histories were needed, which would examine the reality of women’s lives, their relationships and activities, and the forces that thwarted their ambitions. Sometime around 2 billion years ago, a bacterium slipped inside a larger cell, started producing energy there, and became the indispensable powerhouse we know today as the mitochondrion, so the working theory goes. But that old story now has a new twist. Scientists have detected the organelles outside of cells, apparently functioning perfectly well while drifting around the blood of healthy people, according to findings published recently (January 19) in

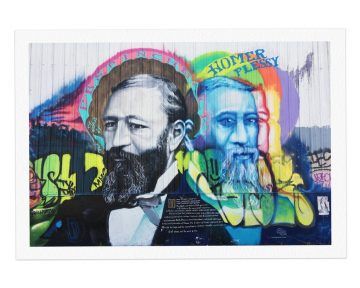

Sometime around 2 billion years ago, a bacterium slipped inside a larger cell, started producing energy there, and became the indispensable powerhouse we know today as the mitochondrion, so the working theory goes. But that old story now has a new twist. Scientists have detected the organelles outside of cells, apparently functioning perfectly well while drifting around the blood of healthy people, according to findings published recently (January 19) in  When Homer Plessy boarded the East Louisiana Railway’s No. 8 train in New Orleans on June 7, 1892, he knew his journey to Covington, La., would be brief. He also knew it could have historic implications. Plessy was a racially mixed shoemaker who had agreed to take part in an act of civil disobedience orchestrated by a New Orleans civil rights organization. On that hot, sticky afternoon he walked into the Press Street Depot, purchased a first-class ticket and took a seat in the whites-only car. The civil rights group had chosen Plessy because he could pass for a white man. It was asserted later in a legal brief that he was seven-eighths white. But a conductor, who was also part of the scheme, stopped him and asked if he was “colored.” Plessy responded that he was. “Then you will have to retire to the colored car,” the conductor ordered.

When Homer Plessy boarded the East Louisiana Railway’s No. 8 train in New Orleans on June 7, 1892, he knew his journey to Covington, La., would be brief. He also knew it could have historic implications. Plessy was a racially mixed shoemaker who had agreed to take part in an act of civil disobedience orchestrated by a New Orleans civil rights organization. On that hot, sticky afternoon he walked into the Press Street Depot, purchased a first-class ticket and took a seat in the whites-only car. The civil rights group had chosen Plessy because he could pass for a white man. It was asserted later in a legal brief that he was seven-eighths white. But a conductor, who was also part of the scheme, stopped him and asked if he was “colored.” Plessy responded that he was. “Then you will have to retire to the colored car,” the conductor ordered. I believe there is much to be learned philosophically from the study of languages that are spoken by only a small number of people, who lack a high degree of political self-determination and are relatively powerless to impose their conception of history, society, and nature on their neighbours; and who also lack much in the way of a textual literary tradition or formal and recognisably modern institutions of knowledge transmission: which for present purposes we may call “indigenous” languages.

I believe there is much to be learned philosophically from the study of languages that are spoken by only a small number of people, who lack a high degree of political self-determination and are relatively powerless to impose their conception of history, society, and nature on their neighbours; and who also lack much in the way of a textual literary tradition or formal and recognisably modern institutions of knowledge transmission: which for present purposes we may call “indigenous” languages. On the Puerto Rican

On the Puerto Rican The annual

The annual  For

For  Most AI systems used today—whether for language translation, playing chess, driving cars, face recognition or medical diagnosis—deploy a technique called machine learning. So-called “convolutional neural -networks,” a silicon-chip version of the highly-interconnected web of neurons in our brains, are trained to spot patterns in data. During training, the strengths of the interconnections between the nodes in the neural network are adjusted until the system can reliably make the right classifications. It might learn, for example, to spot cats in a digital image, or to generate passable translations from Chinese to English. Although the ideas behind neural networks and machine learning go back decades, this type of AI really took off in the 2010s with the introduction of “deep learning”: in essence adding more layers of nodes between the input and output. That’s why DeepMind’s programme AlphaGo is able to defeat expert human players in the very complex board game Go, and Google Translate is now so much better than in its comically clumsy youth (although it’s still not perfect, for reasons I’ll come back to).

Most AI systems used today—whether for language translation, playing chess, driving cars, face recognition or medical diagnosis—deploy a technique called machine learning. So-called “convolutional neural -networks,” a silicon-chip version of the highly-interconnected web of neurons in our brains, are trained to spot patterns in data. During training, the strengths of the interconnections between the nodes in the neural network are adjusted until the system can reliably make the right classifications. It might learn, for example, to spot cats in a digital image, or to generate passable translations from Chinese to English. Although the ideas behind neural networks and machine learning go back decades, this type of AI really took off in the 2010s with the introduction of “deep learning”: in essence adding more layers of nodes between the input and output. That’s why DeepMind’s programme AlphaGo is able to defeat expert human players in the very complex board game Go, and Google Translate is now so much better than in its comically clumsy youth (although it’s still not perfect, for reasons I’ll come back to).