Reed Hundt in the Boston Review:

More than a decade after the financial crises of 2008, the shortcomings of the government’s response have become painfully clear.

More than a decade after the financial crises of 2008, the shortcomings of the government’s response have become painfully clear.

This clarity has unfortunately not been aided by the extensive writings of the three people George W. Bush and Barack Obama charged with putting the fire out: Henry Paulson (Bush’s Treasury secretary), Timothy Geithner (Bush’s New York Fed CEO turned Obama’s Treasury secretary), and Ben Bernanke (chairman of the Federal Reserve for both Bush and Obama). In no other U.S. financial crisis did two successive administrations of opposing parties work together so harmoniously, aiming toward the same goal with similar means. From the moment of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy on September 15, 2008, to Obama’s inauguration on January 20, 2009, the two major parties—one of whose leaders won office on the slogan of hope and change—sought essentially the same legislation, backed the same actions by the executive branch, and even relied on the same person, Geithner, to restore Wall Street’s primacy in shaping investment and wealth allocation.

More here.

We bad-movie watchers have our own anticriteria, the sorts of badness we prefer. Some of us use the term “bad movies” to mean, simply, films that emerge from a supposedly lowbrow genre, or films that are stylized in the manner we tend to label “camp.” (

We bad-movie watchers have our own anticriteria, the sorts of badness we prefer. Some of us use the term “bad movies” to mean, simply, films that emerge from a supposedly lowbrow genre, or films that are stylized in the manner we tend to label “camp.” ( Russia had a Dr. Seuss. Same deal as ours, except his hot decade wasn’t the fifties; it was the twenties. There’s a lot to be said here.

Russia had a Dr. Seuss. Same deal as ours, except his hot decade wasn’t the fifties; it was the twenties. There’s a lot to be said here.

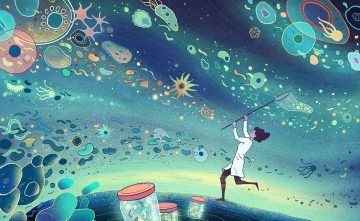

What does a healthy forest look like? A seemingly thriving, verdant wilderness can conceal signs of pollution, disease or invasive species. Only an ecologist can spot problems that could jeopardize the long-term well-being of the entire ecosystem. Microbiome researchers grapple with the same problem. Disruptions to the community of microbes living in the human gut can contribute to the risk and severity of a host of medical conditions. Accordingly, many scientists have become accomplished bacterial naturalists, labouring to catalogue the startling diversity of these commensal communities. Some 500–1,000 bacterial species reside in each person’s intestinal tract, alongside an undetermined number of viruses, fungi and other microbes. Rapid advances in DNA sequencing technology have accelerated the identification of these bacteria, allowing researchers to create ‘field guides’ to the species in the human gut. “We’re starting to get a feeling of who the players are,” says Jeroen Raes, a bioinformatician at VIB, a life-sciences institute in Ghent, Belgium. “But there is still considerable ‘dark matter’.”

What does a healthy forest look like? A seemingly thriving, verdant wilderness can conceal signs of pollution, disease or invasive species. Only an ecologist can spot problems that could jeopardize the long-term well-being of the entire ecosystem. Microbiome researchers grapple with the same problem. Disruptions to the community of microbes living in the human gut can contribute to the risk and severity of a host of medical conditions. Accordingly, many scientists have become accomplished bacterial naturalists, labouring to catalogue the startling diversity of these commensal communities. Some 500–1,000 bacterial species reside in each person’s intestinal tract, alongside an undetermined number of viruses, fungi and other microbes. Rapid advances in DNA sequencing technology have accelerated the identification of these bacteria, allowing researchers to create ‘field guides’ to the species in the human gut. “We’re starting to get a feeling of who the players are,” says Jeroen Raes, a bioinformatician at VIB, a life-sciences institute in Ghent, Belgium. “But there is still considerable ‘dark matter’.” Henry Louis Gates, a renowned and award-winning filmmaker, author of two dozen books, a professor and director of African American studies at Harvard University, has written about race in America. He explores the Civil War, Reconstruction to Jim Crow, the civil rights movement and the state of race relations today. Gates spoke at UNC Charlotte Tuesday for the school’s 2019 Chancellor Speaker Series and at the uptown campus to school donors and city leaders. WFAE’s “All Things Considered” host, Gwendolyn Glenn, caught up with him to talk about race, voting, economics and other issues.

Henry Louis Gates, a renowned and award-winning filmmaker, author of two dozen books, a professor and director of African American studies at Harvard University, has written about race in America. He explores the Civil War, Reconstruction to Jim Crow, the civil rights movement and the state of race relations today. Gates spoke at UNC Charlotte Tuesday for the school’s 2019 Chancellor Speaker Series and at the uptown campus to school donors and city leaders. WFAE’s “All Things Considered” host, Gwendolyn Glenn, caught up with him to talk about race, voting, economics and other issues.

Nations generally want their economies to be rich, robust, and growing. But it’s also important to person to ensure that wealth doesn’t flow only to a few people, but rather that as many people as possible can enjoy the benefits of a healthy economy. As is well known, the best way to balance these interests is a contentious subject. On one side we might find free-market fundamentalists who want to let supply and demand set prices and keep government interference to a minimum, while on the other we might find enthusiasts for very strong government control over all aspects of the economy. Suresh Naidu is an economist who has delved deeply into how economic performance affects and is affected by other notable social factors, from democracy to revolution to slavery. We talk about these, as well as how concentrations of economic power in just a few hands — monopoly and its cousin, monopsony — can distort the best intentions of the free market.

Nations generally want their economies to be rich, robust, and growing. But it’s also important to person to ensure that wealth doesn’t flow only to a few people, but rather that as many people as possible can enjoy the benefits of a healthy economy. As is well known, the best way to balance these interests is a contentious subject. On one side we might find free-market fundamentalists who want to let supply and demand set prices and keep government interference to a minimum, while on the other we might find enthusiasts for very strong government control over all aspects of the economy. Suresh Naidu is an economist who has delved deeply into how economic performance affects and is affected by other notable social factors, from democracy to revolution to slavery. We talk about these, as well as how concentrations of economic power in just a few hands — monopoly and its cousin, monopsony — can distort the best intentions of the free market. Graveyards in India are, for the most part, Muslim graveyards, because Christians make up a miniscule part of the population, and, as you know, Hindus and most other communities cremate their dead. The Muslim graveyard, the kabristan, has always loomed large in the imagination and rhetoric of Hindu nationalists. “Mussalman ka ek hi sthan, kabristan ya Pakistan!”—Only one place for the Mussalman, the graveyard or Pakistan—is among the more frequent war cries of the murderous, sword-wielding militias and vigilante mobs that have overrun India’s streets.

Graveyards in India are, for the most part, Muslim graveyards, because Christians make up a miniscule part of the population, and, as you know, Hindus and most other communities cremate their dead. The Muslim graveyard, the kabristan, has always loomed large in the imagination and rhetoric of Hindu nationalists. “Mussalman ka ek hi sthan, kabristan ya Pakistan!”—Only one place for the Mussalman, the graveyard or Pakistan—is among the more frequent war cries of the murderous, sword-wielding militias and vigilante mobs that have overrun India’s streets. A third of the way through this absorbing and engagingly written book, Albert Costa describes a family meal: “The father speaks Spanish with his wife and his son, but uses Catalan with his daughter. The daughter in turn speaks Catalan with her father but Spanish with the rest of the family, including the grandmother, who only speaks Spanish though she understands Catalan.” It’s what Costa calls “orderly mixing”, and, depending on which restaurants you visit, a common enough situation: everyone is bilingual here, but the language used changes according to who it is directed at. Given that everyone at the table understands both languages, would it not be easier and less confusing if everyone just chose one language and stuck to it? That sounds logical, but the bilingual mind doesn’t work that way. If you do not believe it, Costa suggests “having a conversation with a friend in the language you do not usually use and see how far you get”.

A third of the way through this absorbing and engagingly written book, Albert Costa describes a family meal: “The father speaks Spanish with his wife and his son, but uses Catalan with his daughter. The daughter in turn speaks Catalan with her father but Spanish with the rest of the family, including the grandmother, who only speaks Spanish though she understands Catalan.” It’s what Costa calls “orderly mixing”, and, depending on which restaurants you visit, a common enough situation: everyone is bilingual here, but the language used changes according to who it is directed at. Given that everyone at the table understands both languages, would it not be easier and less confusing if everyone just chose one language and stuck to it? That sounds logical, but the bilingual mind doesn’t work that way. If you do not believe it, Costa suggests “having a conversation with a friend in the language you do not usually use and see how far you get”. The footprints of a child are small but on November 14, 1960, six-year-old Ruby Bridges walked with purpose as she became the first African American student to integrate an elementary school in the South. This venture leads to the advancement of the Civil Rights Movement and created a pathway for further integration across the southern parts of the U.S.

The footprints of a child are small but on November 14, 1960, six-year-old Ruby Bridges walked with purpose as she became the first African American student to integrate an elementary school in the South. This venture leads to the advancement of the Civil Rights Movement and created a pathway for further integration across the southern parts of the U.S. When Darwin wrote the Origin of Species, he famously closed the book with the provocative promise that “light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.”

When Darwin wrote the Origin of Species, he famously closed the book with the provocative promise that “light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.” The trebling of tuition fees would unleash a new golden age for English universities, or so we were told. They would become financially sustainable, competitive, liberated from stifling bureaucracy and responsive to the needs of students. And yet, nearly a decade later, higher education is in crisis.

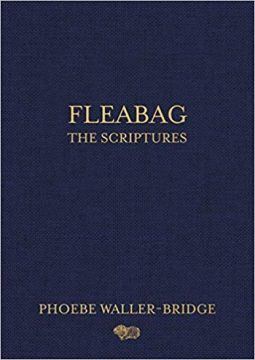

The trebling of tuition fees would unleash a new golden age for English universities, or so we were told. They would become financially sustainable, competitive, liberated from stifling bureaucracy and responsive to the needs of students. And yet, nearly a decade later, higher education is in crisis. The title of Fleabag: The Scriptures (Ballantine Books, $28) is a cheeky play on words: It refers to the shooting scripts for the television comedy Fleabag, which are reproduced here in full, and it also refers to the fact that the second (and, if creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge is to be believed, final) season of the show, which debuted on Amazon Prime in May 2019, is about the main character’s romantic attachment to an unattainable Catholic priest. But it also acknowledges that Waller-Bridge’s words—printed out on creamy paper stock, bound inside a smooth navy-blue cover, and embossed with gold serif letters like a Gideon Bible—have become a new kind of religious text, albeit one that preaches primarily to secular women living in major metropolitan areas. And there is some truth to this visual provocation: If anyone had a truly blessed year, it was Phoebe Waller-Bridge. A

The title of Fleabag: The Scriptures (Ballantine Books, $28) is a cheeky play on words: It refers to the shooting scripts for the television comedy Fleabag, which are reproduced here in full, and it also refers to the fact that the second (and, if creator Phoebe Waller-Bridge is to be believed, final) season of the show, which debuted on Amazon Prime in May 2019, is about the main character’s romantic attachment to an unattainable Catholic priest. But it also acknowledges that Waller-Bridge’s words—printed out on creamy paper stock, bound inside a smooth navy-blue cover, and embossed with gold serif letters like a Gideon Bible—have become a new kind of religious text, albeit one that preaches primarily to secular women living in major metropolitan areas. And there is some truth to this visual provocation: If anyone had a truly blessed year, it was Phoebe Waller-Bridge. A