Ferenc Laczó in Taxis:

György Konrád passed away after prolonged illness on September 13, 2019, at the age of 86, two days after the architect László Rajk Jr. (who had just turned 70) and less than two months after the philosopher Ágnes Heller at the age of 90. The departure of three prominent Hungarian public intellectuals admired in Hungary and the world over has led commentators — perhaps especially since these deaths came so soon after those of Imre Kertész and Péter Esterházy — to mark “the passing of a key intellectual generation” and even “the end of an era.”

György Konrád passed away after prolonged illness on September 13, 2019, at the age of 86, two days after the architect László Rajk Jr. (who had just turned 70) and less than two months after the philosopher Ágnes Heller at the age of 90. The departure of three prominent Hungarian public intellectuals admired in Hungary and the world over has led commentators — perhaps especially since these deaths came so soon after those of Imre Kertész and Péter Esterházy — to mark “the passing of a key intellectual generation” and even “the end of an era.”

Konrád and Heller both belonged to that most unfortunate generation of Central and Eastern European Jews who were born during the Great Depression at the time of the rise of Nazism and Stalinist mass crimes. Along with novelists Imre Kertész and István Eörsi, philosophers Ferenc Fehér and György Márkus, historians György Ránki and Iván T. Berend, and economist János Kornai, Konrád and Heller were members of the most intellectually exciting generational cohort of Jews in twentieth-century Hungary — perhaps the most internationally renowned such group in modern Hungary, with the possible exception of the towering figures of György Lukács, Karl Polányi and Karl Mannheim, all of whom were born in Budapest between 1886 and 1893.

More here.

How to Keep Your House from Becoming a Disaster Area

How to Keep Your House from Becoming a Disaster Area Think of Bloomsbury and what might spring to mind is its “orderly profligacy and passionate coldness”. (The phrase is Elizabeth Hardwick’s, in one of her early essay/reviews for The New York Review of Books.) But there was always more to Bloomsbury than this suggests. First came the actual geographical locality – the streets and squares and architecture of a part of central London – and then the associations imposed on top of it: literary, scholarly, urbane or bohemian. Bloomsbury as an idea continues to reverberate, in ways both gossipy and profound. Bedazzling sexual intrigues and a spot of intellectual hauteur are only a part of it. And however many words have been expended on Bloomsbury (and there have been a lot), there is always more to be said. Francesca Wade’s superbly engaging Square Haunting takes up the theme, but at the same time narrows and intensifies its focus. Wade homes in on a single square, Mecklenburgh Square, which is not at the heart of the potent locality but rather on its periphery.

Think of Bloomsbury and what might spring to mind is its “orderly profligacy and passionate coldness”. (The phrase is Elizabeth Hardwick’s, in one of her early essay/reviews for The New York Review of Books.) But there was always more to Bloomsbury than this suggests. First came the actual geographical locality – the streets and squares and architecture of a part of central London – and then the associations imposed on top of it: literary, scholarly, urbane or bohemian. Bloomsbury as an idea continues to reverberate, in ways both gossipy and profound. Bedazzling sexual intrigues and a spot of intellectual hauteur are only a part of it. And however many words have been expended on Bloomsbury (and there have been a lot), there is always more to be said. Francesca Wade’s superbly engaging Square Haunting takes up the theme, but at the same time narrows and intensifies its focus. Wade homes in on a single square, Mecklenburgh Square, which is not at the heart of the potent locality but rather on its periphery. As I fall asleep, I leave my body and my soul behind, all the while palpably returning back to my body and my soul. But what is actually going on here? It is not my body that has changed, or my soul, but rather my relation to both. By day, when I’m awake, I usually observe my body from without, and although I am only capable of imagining myself as a physical body, I don’t identify myself with it. In a similar way, I don’t fully identify with my soul either. If I’m awake, for the most part I think of it, as it were, as someone (or something), which cannot exist without me, and yet is not completely identical to me. I would almost speak of it in the third-person singular. This is Descartes’s final inheritance; not even I can avoid his influence. In the moment when I began to speak about the body or about the soul, I unwittingly behave as if it were possible to distinguish between them. And in doing so I imperceptibly differentiate myself from them. I create a differentiation between the soul and the body.

As I fall asleep, I leave my body and my soul behind, all the while palpably returning back to my body and my soul. But what is actually going on here? It is not my body that has changed, or my soul, but rather my relation to both. By day, when I’m awake, I usually observe my body from without, and although I am only capable of imagining myself as a physical body, I don’t identify myself with it. In a similar way, I don’t fully identify with my soul either. If I’m awake, for the most part I think of it, as it were, as someone (or something), which cannot exist without me, and yet is not completely identical to me. I would almost speak of it in the third-person singular. This is Descartes’s final inheritance; not even I can avoid his influence. In the moment when I began to speak about the body or about the soul, I unwittingly behave as if it were possible to distinguish between them. And in doing so I imperceptibly differentiate myself from them. I create a differentiation between the soul and the body. Rape, writes Christina Lamb at the start of this deeply traumatic and important book, is “the cheapest weapon known to man”. It is also one of the oldest, with the Book of Deuteronomy giving its blessing to soldiers who find “a beautiful woman” among the captives taken in battle. If “you desire to take her”, it says, “you may”. As the American writer

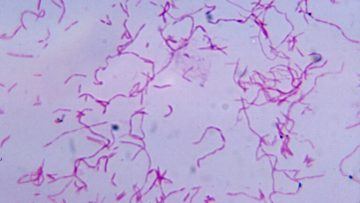

Rape, writes Christina Lamb at the start of this deeply traumatic and important book, is “the cheapest weapon known to man”. It is also one of the oldest, with the Book of Deuteronomy giving its blessing to soldiers who find “a beautiful woman” among the captives taken in battle. If “you desire to take her”, it says, “you may”. As the American writer  The many companies developing liquid biopsies to try to detect cancer early have so far largely mined the blood in search of things like mutations and epigenetic changes in human DNA shed by tumor cells. Now, new research raises the possibility that liquid biopsies could be used to spot cancer in a totally different way: by hunting for the DNA of bacteria and viruses released from tumors into the bloodstream. It’s a hypothesis that, if validated with more study, could usher in an entirely new class of diagnostics for cancer. In a

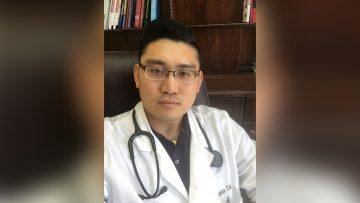

The many companies developing liquid biopsies to try to detect cancer early have so far largely mined the blood in search of things like mutations and epigenetic changes in human DNA shed by tumor cells. Now, new research raises the possibility that liquid biopsies could be used to spot cancer in a totally different way: by hunting for the DNA of bacteria and viruses released from tumors into the bloodstream. It’s a hypothesis that, if validated with more study, could usher in an entirely new class of diagnostics for cancer. In a  A New Jersey physician assistant who was the state’s first COVID-19 patient is speaking out from his hospital bed, calling his illness “severe” and raising concerns about his treatment. James Cai, a 32-year-old non-smoker with no other health conditions, has been at Hackensack University Medical Center for about a week and says his illness has worsened significantly over that time. “In the beginning, they just treat me like normal flu. They say I’m young, I’m not going to die, but they don’t know the truth about corona[virus],” Cai said during an

A New Jersey physician assistant who was the state’s first COVID-19 patient is speaking out from his hospital bed, calling his illness “severe” and raising concerns about his treatment. James Cai, a 32-year-old non-smoker with no other health conditions, has been at Hackensack University Medical Center for about a week and says his illness has worsened significantly over that time. “In the beginning, they just treat me like normal flu. They say I’m young, I’m not going to die, but they don’t know the truth about corona[virus],” Cai said during an  I’ve learned a lot since the release of

I’ve learned a lot since the release of  Ashutosh Varshney, a Brown University professor and

Ashutosh Varshney, a Brown University professor and  Researchers are calling on citizen scientists to play a free online game called

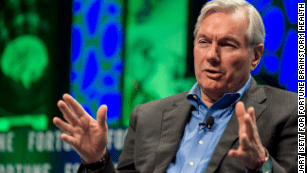

Researchers are calling on citizen scientists to play a free online game called  Michael Osterholm, the infectious disease expert who has been warning for a decade and a half that the world will face a pandemic, says the US is ill-prepared to combat the coronavirus due to a shortage of equipment and supplies.

Michael Osterholm, the infectious disease expert who has been warning for a decade and a half that the world will face a pandemic, says the US is ill-prepared to combat the coronavirus due to a shortage of equipment and supplies. David Cutler: Yeah, one of the continual vexing points about U.S. healthcare is why it’s so expensive. There are a few reasons why the U.S. spends more than other rich countries. Obviously, in poor countries, there’s an enormous difference in the nature of medical care. Relative to other rich countries, I would say there are three principle reasons why the U.S. spends more. The first is that it’s administratively much more costly. So we have lots of people involved in submitting bills, and adjudicating claims and figuring out what services someone is allowed to receive and not allowed to receive and what you need to do in order to receive those services. And all of that involves people, and people are very expensive. And so probably the biggest contributor to the higher spending in the U.S. is that.

David Cutler: Yeah, one of the continual vexing points about U.S. healthcare is why it’s so expensive. There are a few reasons why the U.S. spends more than other rich countries. Obviously, in poor countries, there’s an enormous difference in the nature of medical care. Relative to other rich countries, I would say there are three principle reasons why the U.S. spends more. The first is that it’s administratively much more costly. So we have lots of people involved in submitting bills, and adjudicating claims and figuring out what services someone is allowed to receive and not allowed to receive and what you need to do in order to receive those services. And all of that involves people, and people are very expensive. And so probably the biggest contributor to the higher spending in the U.S. is that. If you tell me that one of the world’s leading neuroscientists has developed a theory of how the brain works that also has implications for the origin and nature of life more broadly, and uses concepts of entropy and information in a central way — well, you know I’m going to be all over that. So it’s my great pleasure to present this conversation with Karl Friston, who has done exactly that. One of the most highly-cited neuroscientists now living, Friston has proposed that we understand the brain in terms of a

If you tell me that one of the world’s leading neuroscientists has developed a theory of how the brain works that also has implications for the origin and nature of life more broadly, and uses concepts of entropy and information in a central way — well, you know I’m going to be all over that. So it’s my great pleasure to present this conversation with Karl Friston, who has done exactly that. One of the most highly-cited neuroscientists now living, Friston has proposed that we understand the brain in terms of a  We tend to think of civility as maintaining a courteous and calm demeanor in political debate. But that can’t be correct. Keeping your cool is good, but courtesy and calmness can also be patronizing. Moreover, fervor is sometimes called for in politics. So civility is better understood as the avoidance of gratuitous escalation and excessive hostility. This allows for political antagonism but recognizes its limits.

We tend to think of civility as maintaining a courteous and calm demeanor in political debate. But that can’t be correct. Keeping your cool is good, but courtesy and calmness can also be patronizing. Moreover, fervor is sometimes called for in politics. So civility is better understood as the avoidance of gratuitous escalation and excessive hostility. This allows for political antagonism but recognizes its limits. B

B