Michael Marshall in Nature:

It was the finger seen around the world. In 2008, archaeologists working in Denisova Cave in southern Siberia, Russia, uncovered a tiny bone: the tip of the little finger of an ancient human that lived there tens of thousands of years ago. The fragment didn’t seem remarkable, but it was well preserved, giving researchers hope that it harboured intact DNA. A team of geneticists led by Johannes Krause at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, removed 30 milligrams of bone and managed to extract enough intact DNA to analyse it. They were able to sequence the entire mitochondrial genome — and were shocked by what they found. The DNA did not match that of modern humans, or of Neanderthals, the other likely candidate1. It was a new population, which they dubbed the Denisovans, after the cave.

It was the finger seen around the world. In 2008, archaeologists working in Denisova Cave in southern Siberia, Russia, uncovered a tiny bone: the tip of the little finger of an ancient human that lived there tens of thousands of years ago. The fragment didn’t seem remarkable, but it was well preserved, giving researchers hope that it harboured intact DNA. A team of geneticists led by Johannes Krause at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, removed 30 milligrams of bone and managed to extract enough intact DNA to analyse it. They were able to sequence the entire mitochondrial genome — and were shocked by what they found. The DNA did not match that of modern humans, or of Neanderthals, the other likely candidate1. It was a new population, which they dubbed the Denisovans, after the cave.

When the team announced this result in March 2010, it caused a sensation. Up to that point, researchers had used preserved bones to identify every species or population of hominin — the group that includes modern and ancient humans and their immediate ancestors. “Denisovans were created from DNA work,” says palaeoanthropologist Chris Stringer at the Natural History Museum in London. Nine months later came the second bombshell. Krause and his colleagues had obtained the entire nuclear genome from the finger bone, which yielded much more information. It showed that the Denisovans were a sister group to the Neanderthals, which lived in Europe and western Asia for hundreds of thousands of years.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Art criticism is thriving. It’s taking on new forms, shedding old skin, and adapting to novel venues. It’s as alive and relevant as ever, still generating conversation and controversy. Instead of fizzling out, it’s being embraced by new generations of critics, whether in these pages or on Substack, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok (no matter the platform, it always comes down to writing). It’s a buzzing genre that attracts readers of all ages, from septum-pierced college students to cigar-puffing art collectors.

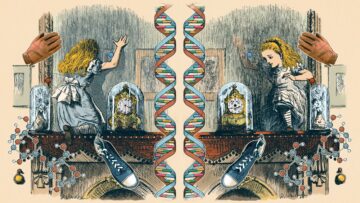

Art criticism is thriving. It’s taking on new forms, shedding old skin, and adapting to novel venues. It’s as alive and relevant as ever, still generating conversation and controversy. Instead of fizzling out, it’s being embraced by new generations of critics, whether in these pages or on Substack, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok (no matter the platform, it always comes down to writing). It’s a buzzing genre that attracts readers of all ages, from septum-pierced college students to cigar-puffing art collectors. After her adventures in Wonderland, the fictional Alice stepped through the mirror above her fireplace in Lewis Carroll’s 1871 novel Through the Looking-Glass to discover how the reflected realm differed from her own. She found that the books were all written in reverse, and the people were “living backwards,” navigating a world where effects preceded their causes.

After her adventures in Wonderland, the fictional Alice stepped through the mirror above her fireplace in Lewis Carroll’s 1871 novel Through the Looking-Glass to discover how the reflected realm differed from her own. She found that the books were all written in reverse, and the people were “living backwards,” navigating a world where effects preceded their causes. For much of the 20th century, young Americans were seen as free speech’s fiercest defenders. But now, young Americans are growing more skeptical of free speech.

For much of the 20th century, young Americans were seen as free speech’s fiercest defenders. But now, young Americans are growing more skeptical of free speech. Meet my patient Mrs. L. R. She’s 98 years young and has never suffered a day of serious illness in her long life. She was referred to me by her primary care physician to assess her

Meet my patient Mrs. L. R. She’s 98 years young and has never suffered a day of serious illness in her long life. She was referred to me by her primary care physician to assess her  It was a cold, gray afternoon in December, and at the American Museum of Natural History, a half million leaf-cutter ants were hunkered down in their homes. The ants typically spend their days harvesting slivers of leaves, which they use to grow expansive fungal gardens that serve as both food and shelter. On many days, visitors to the

It was a cold, gray afternoon in December, and at the American Museum of Natural History, a half million leaf-cutter ants were hunkered down in their homes. The ants typically spend their days harvesting slivers of leaves, which they use to grow expansive fungal gardens that serve as both food and shelter. On many days, visitors to the  What is the history of bureaucracies? Where did the concept originate, and how has it evolved?

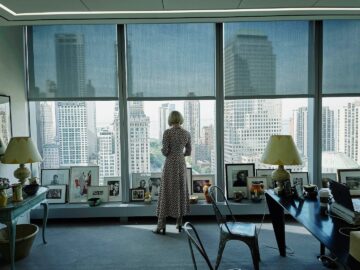

What is the history of bureaucracies? Where did the concept originate, and how has it evolved? Wintour is the longtime editor in chief of Vogue and the chief content officer for the publishing behemoth Condé Nast, whose stable of magazines includes Bon Appetit, Teen Vogue and New Yorker. She is the mastermind behind the Met Gala, which lit up the pop culture cosmos earlier this month. In many respects, Wintour, at 75, remains the most recognizable face of the fashion establishment. But fashion, at the level where Wintour has long served as gatekeeper, and with its subjective assessment of aesthetics, has struggled more than most industries with diversity and inclusivity, from the pages of its magazines to its corporate boardrooms. And despite moments of intense focus on racial justice, big changes have often been superficial and real change has been slow.

Wintour is the longtime editor in chief of Vogue and the chief content officer for the publishing behemoth Condé Nast, whose stable of magazines includes Bon Appetit, Teen Vogue and New Yorker. She is the mastermind behind the Met Gala, which lit up the pop culture cosmos earlier this month. In many respects, Wintour, at 75, remains the most recognizable face of the fashion establishment. But fashion, at the level where Wintour has long served as gatekeeper, and with its subjective assessment of aesthetics, has struggled more than most industries with diversity and inclusivity, from the pages of its magazines to its corporate boardrooms. And despite moments of intense focus on racial justice, big changes have often been superficial and real change has been slow. A pandemic is never only about biological contagion. Much of what we feel, think, and do—far more than I want to admit—is the product of what we perceive or unconsciously mimic in the world around us. Laughter is contagious, and yawns—even chimpanzees find yawns contagious. I realize only now, in the enforced quiet, how I absorbed the pace and values of the society around me. My mind was quiet, if concerned, as I watched the infectiousness of fear, panic, and hysteria; of rationalization or mystification; of courage. Ideas and beliefs, good information and bad information, enthusiasm and advice and funny memes spread as fast as the virus.

A pandemic is never only about biological contagion. Much of what we feel, think, and do—far more than I want to admit—is the product of what we perceive or unconsciously mimic in the world around us. Laughter is contagious, and yawns—even chimpanzees find yawns contagious. I realize only now, in the enforced quiet, how I absorbed the pace and values of the society around me. My mind was quiet, if concerned, as I watched the infectiousness of fear, panic, and hysteria; of rationalization or mystification; of courage. Ideas and beliefs, good information and bad information, enthusiasm and advice and funny memes spread as fast as the virus. The system, called AlphaEvolve, combines the creativity of a large language model (LLM) with algorithms that can scrutinize the model’s suggestions to filter and improve solutions. It was described in a white paper

The system, called AlphaEvolve, combines the creativity of a large language model (LLM) with algorithms that can scrutinize the model’s suggestions to filter and improve solutions. It was described in a white paper  One of the most intriguing ways of conceptualizing the scorched landscape of the 2020s is the theory of ‘hyperpolitics’, advanced by the Belgian political philosopher Anton Jäger. Our current predicament, he writes, is one of “extreme politicization without political consequences.” While ideological commitment is ubiquitous, institutional outlets for it are absent. While contestation is fierce, the form it takes is frustratingly ephemeral. Politics is at once everywhere and nowhere – permeating our everyday lives but failing to influence state policy, which continues on much the same neoliberal trajectory, with minor variations here and there.

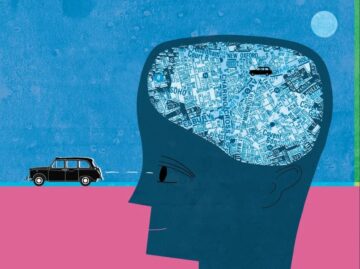

One of the most intriguing ways of conceptualizing the scorched landscape of the 2020s is the theory of ‘hyperpolitics’, advanced by the Belgian political philosopher Anton Jäger. Our current predicament, he writes, is one of “extreme politicization without political consequences.” While ideological commitment is ubiquitous, institutional outlets for it are absent. While contestation is fierce, the form it takes is frustratingly ephemeral. Politics is at once everywhere and nowhere – permeating our everyday lives but failing to influence state policy, which continues on much the same neoliberal trajectory, with minor variations here and there. London cabbies

London cabbies In April 2024, Favreau visited the White House with his podcast co-hosts and several other “influencers” at a meet-and-greet the night before the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner. Biden was incoherent and frail; he kept telling stories that no one could understand. Sixteen months had passed, but he seemed to have aged a half-century. An alarmed Favreau approached a White House aide, but his concerns were brushed off. The president was just tired, he was told. It was the end of a long week. There was no reason for concern. Two months later, Biden delivered the single worst performance in the 60-year history of televised presidential debates, dooming his reelection campaign, destroying his presidency and essentially delivering the country to Donald Trump.

In April 2024, Favreau visited the White House with his podcast co-hosts and several other “influencers” at a meet-and-greet the night before the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner. Biden was incoherent and frail; he kept telling stories that no one could understand. Sixteen months had passed, but he seemed to have aged a half-century. An alarmed Favreau approached a White House aide, but his concerns were brushed off. The president was just tired, he was told. It was the end of a long week. There was no reason for concern. Two months later, Biden delivered the single worst performance in the 60-year history of televised presidential debates, dooming his reelection campaign, destroying his presidency and essentially delivering the country to Donald Trump. On a spring day in 1989, a container ship arrived in New York harbor from Eemshaven, a deepwater port in the Netherlands. The Vessel, named the Bibby Resolution, belonged to a well-established Liverpool shipping line, one whose founder had invested in the Atlantic slave trade two hundred years before. But while the company that owned it had a history that went back centuries, the ship itself was unmistakably a product of the late twentieth century.

On a spring day in 1989, a container ship arrived in New York harbor from Eemshaven, a deepwater port in the Netherlands. The Vessel, named the Bibby Resolution, belonged to a well-established Liverpool shipping line, one whose founder had invested in the Atlantic slave trade two hundred years before. But while the company that owned it had a history that went back centuries, the ship itself was unmistakably a product of the late twentieth century.