Amy Maxmen in Nature:

Hospitals in New York City are gearing up to use the blood of people who have recovered from COVID-19 as a possible antidote for the disease. Researchers hope that the century-old approach of infusing patients with the antibody-laden blood of those who have survived an infection will help the metropolis — now the US epicentre of the outbreak — to avoid the fate of Italy, where intensive-care units (ICUs) are so crowded that doctors have turned away patients who need ventilators to breathe. The efforts follow studies in China that attempted the measure with plasma — the fraction of blood that contains antibodies, but not red blood cells — from people who had recovered from COVID-19. But these studies have reported only preliminary results so far. The convalescent plasma approach has also seen modest success during past severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Ebola outbreaks — but US researchers are hoping to increase the value of the treatment by selecting donor blood that is packed with antibodies and giving it to the patients who are most likely to benefit.

Hospitals in New York City are gearing up to use the blood of people who have recovered from COVID-19 as a possible antidote for the disease. Researchers hope that the century-old approach of infusing patients with the antibody-laden blood of those who have survived an infection will help the metropolis — now the US epicentre of the outbreak — to avoid the fate of Italy, where intensive-care units (ICUs) are so crowded that doctors have turned away patients who need ventilators to breathe. The efforts follow studies in China that attempted the measure with plasma — the fraction of blood that contains antibodies, but not red blood cells — from people who had recovered from COVID-19. But these studies have reported only preliminary results so far. The convalescent plasma approach has also seen modest success during past severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Ebola outbreaks — but US researchers are hoping to increase the value of the treatment by selecting donor blood that is packed with antibodies and giving it to the patients who are most likely to benefit.

A key advantage to convalescent plasma is that it’s available immediately, whereas drugs and vaccines take months or years to develop. Infusing blood in this way seems to be relatively safe, provided that it is screened for viruses and other components that could cause an infection. Scientists who have led the charge to use plasma want to deploy it now as a stopgap measure, to keep serious infections at bay and hospitals afloat as a tsunami of cases comes crashing their way. “Every patient that we can keep out of the ICU is a huge logistical victory because there are traffic jams in hospitals,” says Michael Joyner, an anaesthesiologist and physiologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. “We need to get this on board as soon as possible, and pray that a surge doesn’t overwhelm places like New York and the west coast.” On 23 March, New York governor Andrew Cuomo announced the plan to use convalescent plasma to aid the response in the state, which has more than 25,000 infections, with 210 deaths. “We think it shows promise,” he said. Thanks to the researchers’ efforts, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) today announced that it will permit the emergency use of plasma for patients in need.

More here.

I personally believe we will blunt this epidemic, but I think we wasted a good four to six weeks largely because of lack of testing and lack of a certain preparedness. But I think we could still make a difference and bring it under control with very harsh measures.

I personally believe we will blunt this epidemic, but I think we wasted a good four to six weeks largely because of lack of testing and lack of a certain preparedness. But I think we could still make a difference and bring it under control with very harsh measures. As the subtitle of this collection of essays plainly implies, Barnes did modernism her way. She might have been ambivalent about the movement, resulting in what Daniela Caselli calls her “aesthetics of uncertainty”. But there is no doubting her credentials as a modernist mover and shaker: as a Left Bank journalist, an interviewer of James Joyce, the author of that late modernist masterpiece Nightwood (1936) and the beneficiary of Peggy Guggenheim’s largesse. Yet Barnes also slips away from easy chronology and canonization, not least because of her longevity. Born in 1892, she died in 1982, at the age of ninety, having outlived many of her peers by decades. On its dust jacket and between chapters, Shattered Objects acknowledges that longevity by featuring photographs of her in later life. The visual representation matters. Barnes’s reputation has long been framed as a story of decline – as that of a once dazzling author turned (by the mid-century) recluse.

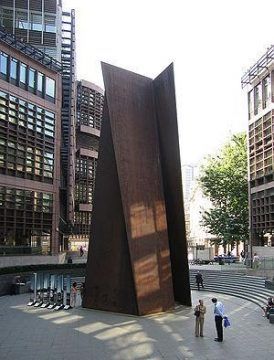

As the subtitle of this collection of essays plainly implies, Barnes did modernism her way. She might have been ambivalent about the movement, resulting in what Daniela Caselli calls her “aesthetics of uncertainty”. But there is no doubting her credentials as a modernist mover and shaker: as a Left Bank journalist, an interviewer of James Joyce, the author of that late modernist masterpiece Nightwood (1936) and the beneficiary of Peggy Guggenheim’s largesse. Yet Barnes also slips away from easy chronology and canonization, not least because of her longevity. Born in 1892, she died in 1982, at the age of ninety, having outlived many of her peers by decades. On its dust jacket and between chapters, Shattered Objects acknowledges that longevity by featuring photographs of her in later life. The visual representation matters. Barnes’s reputation has long been framed as a story of decline – as that of a once dazzling author turned (by the mid-century) recluse. When you look at the work of an artist like Richard Serra, or better yet, stand next to a classic Serra piece, you begin to understand how important the physical problem of balance and uprightness is for contemporary sculpture. Take one such classic work, Fulcrum (1987). The work consists of five fifty-five-foot tall slabs of COR-TEN steel. It dominates one of the entrances to the Liverpool Street station in London. Standing next to Fulcrum can be genuinely scary, all the more so when (and if) you realize that the huge slabs of steel are balanced one against the other simply by weight and angle. So, these slabs of steel can, theoretically, kill you. In fact, Serra’s sculptures have killed before and might do so again. Serra’s Sculpture No. 3 famously ended the life of a rigger named Raymond Johnson, who was crushed by it during installation at the Walker Art Center in 1977.

When you look at the work of an artist like Richard Serra, or better yet, stand next to a classic Serra piece, you begin to understand how important the physical problem of balance and uprightness is for contemporary sculpture. Take one such classic work, Fulcrum (1987). The work consists of five fifty-five-foot tall slabs of COR-TEN steel. It dominates one of the entrances to the Liverpool Street station in London. Standing next to Fulcrum can be genuinely scary, all the more so when (and if) you realize that the huge slabs of steel are balanced one against the other simply by weight and angle. So, these slabs of steel can, theoretically, kill you. In fact, Serra’s sculptures have killed before and might do so again. Serra’s Sculpture No. 3 famously ended the life of a rigger named Raymond Johnson, who was crushed by it during installation at the Walker Art Center in 1977. Raza argues that we have made little progress in fighting cancer over the last 50 years. The tools available to oncologists haven’t changed much–the bulk of the progress that has been made has been through earlier and earlier detection rather than more effective or compassionate treatment options. Raza wants to see a different approach from the current strategy of marginal improvements on narrowly defined problems at the cellular level. Instead, she suggests an alternative approach that might better take account of the complexity of human beings and the way that cancer morphs and spreads differently across people and even within individuals. The conversation includes the challenges of dealing with dying patients, the importance of listening, and the bittersweet nature of our mortality.

Raza argues that we have made little progress in fighting cancer over the last 50 years. The tools available to oncologists haven’t changed much–the bulk of the progress that has been made has been through earlier and earlier detection rather than more effective or compassionate treatment options. Raza wants to see a different approach from the current strategy of marginal improvements on narrowly defined problems at the cellular level. Instead, she suggests an alternative approach that might better take account of the complexity of human beings and the way that cancer morphs and spreads differently across people and even within individuals. The conversation includes the challenges of dealing with dying patients, the importance of listening, and the bittersweet nature of our mortality. Those young movie nuts would launch the French New Wave, along with Rohmer, who was its virtual godfather; yet it took him two decades to put his ideas into practice. What made the difference for this group’s movies was a new mode of production—scant budget, small crew, rapid shooting. For Rohmer, these methods helped him fuse his way of filming with his way of living—and

Those young movie nuts would launch the French New Wave, along with Rohmer, who was its virtual godfather; yet it took him two decades to put his ideas into practice. What made the difference for this group’s movies was a new mode of production—scant budget, small crew, rapid shooting. For Rohmer, these methods helped him fuse his way of filming with his way of living—and  To most people, the assertion that we are living in Skinner boxes might sound alarming, but The Age of Surveillance Capitalism goes darker still. Skinner, at least, saw himself as a do-gooder who would save humanity from its own delusions. His behavioral engineering was meant to build a happier humanity, one finally at peace with our lack of agency. “What is love,” Skinner wrote, “except another name for the use of positive reinforcement?”

To most people, the assertion that we are living in Skinner boxes might sound alarming, but The Age of Surveillance Capitalism goes darker still. Skinner, at least, saw himself as a do-gooder who would save humanity from its own delusions. His behavioral engineering was meant to build a happier humanity, one finally at peace with our lack of agency. “What is love,” Skinner wrote, “except another name for the use of positive reinforcement?” When the plague came to London in 1665, Londoners lost their wits. They consulted astrologers, quacks, the Bible. They searched their bodies for signs, tokens of the disease: lumps, blisters, black spots. They begged for prophecies; they paid for predictions; they prayed; they yowled. They closed their eyes; they covered their ears. They wept in the street. They read alarming almanacs: “Certain it is, books frighted them terribly.” The government, keen to contain the panic, attempted “to suppress the Printing of such Books as terrify’d the People,” according to Daniel Defoe, in “A Journal of the Plague Year,” a history that he wrote in tandem with an advice manual called “Due Preparations for the Plague,” in 1722, a year when people feared that the disease might leap across the English Channel again, after having journeyed from the Middle East to Marseille and points north on a merchant ship. Defoe hoped that his books would be useful “both to us and to posterity, though we should be spared from that portion of this bitter cup.” That bitter cup has come out of its cupboard.

When the plague came to London in 1665, Londoners lost their wits. They consulted astrologers, quacks, the Bible. They searched their bodies for signs, tokens of the disease: lumps, blisters, black spots. They begged for prophecies; they paid for predictions; they prayed; they yowled. They closed their eyes; they covered their ears. They wept in the street. They read alarming almanacs: “Certain it is, books frighted them terribly.” The government, keen to contain the panic, attempted “to suppress the Printing of such Books as terrify’d the People,” according to Daniel Defoe, in “A Journal of the Plague Year,” a history that he wrote in tandem with an advice manual called “Due Preparations for the Plague,” in 1722, a year when people feared that the disease might leap across the English Channel again, after having journeyed from the Middle East to Marseille and points north on a merchant ship. Defoe hoped that his books would be useful “both to us and to posterity, though we should be spared from that portion of this bitter cup.” That bitter cup has come out of its cupboard.

When I became an attending physician at New York–Presbyterian’s Weill Cornell Hospital last summer, after graduating from a residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, I became a hospitalist: a doctor of general internal medicine who takes care of patients for the duration of their inpatient hospital care. Besides my own writing and research, I also teach medical students and residents in a variety of courses and electives. But for me, as for roughly a million other doctors in the United States, that regular routine is changing very suddenly. Part of the challenge we’re facing with Covid-19 is that even knowing this is an event of shocking magnitude, we are not yet able to measure or foresee exactly how fast the disease’s progress through the world’s population will be.

When I became an attending physician at New York–Presbyterian’s Weill Cornell Hospital last summer, after graduating from a residency at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, I became a hospitalist: a doctor of general internal medicine who takes care of patients for the duration of their inpatient hospital care. Besides my own writing and research, I also teach medical students and residents in a variety of courses and electives. But for me, as for roughly a million other doctors in the United States, that regular routine is changing very suddenly. Part of the challenge we’re facing with Covid-19 is that even knowing this is an event of shocking magnitude, we are not yet able to measure or foresee exactly how fast the disease’s progress through the world’s population will be.

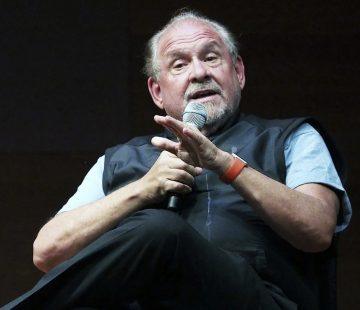

LARRY BRILLIANT SAYS

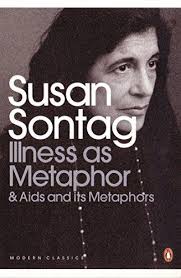

LARRY BRILLIANT SAYS Punitive notions of disease have a long history, and such notions are particularly active with cancer. There is the “fight” or “crusade” against cancer; cancer is the “killer” disease; people who have cancer are “cancer victims.” Ostensibly, the illness is the culprit. But it is also the cancer patient who is made culpable. Widely believed psychological theories of disease assign to the ill the ultimate responsibility both for falling ill and for getting well. And conventions of treating cancer as no mere disease but a demonic enemy make cancer not just a lethal disease but a shameful one. Leprosy in its heyday aroused a similarly disproportionate sense of horror. In the Middle Ages the leper was a social text in which corruption was made visible; an exemplum, an emblem of decay. Nothing is more punitive than to give a disease a meaning—that meaning being invariably a moralistic one. Any important disease, whose physical etiology is not understood, and for which treatment is ineffectual, tends to be awash in significance. First, the subjects of deepest dread (corruption, decay, pollution, anomie, weakness) are identified with the disease. The disease itself becomes a metaphor. Then, in the name of the disease (that is, using it as a metaphor), that horror is imposed on other things. The disease becomes adjectival. Something is said to be disease-like, meaning that it is disgusting or ugly. In French, a crumbling stone façade is still “lépreuse.”

Punitive notions of disease have a long history, and such notions are particularly active with cancer. There is the “fight” or “crusade” against cancer; cancer is the “killer” disease; people who have cancer are “cancer victims.” Ostensibly, the illness is the culprit. But it is also the cancer patient who is made culpable. Widely believed psychological theories of disease assign to the ill the ultimate responsibility both for falling ill and for getting well. And conventions of treating cancer as no mere disease but a demonic enemy make cancer not just a lethal disease but a shameful one. Leprosy in its heyday aroused a similarly disproportionate sense of horror. In the Middle Ages the leper was a social text in which corruption was made visible; an exemplum, an emblem of decay. Nothing is more punitive than to give a disease a meaning—that meaning being invariably a moralistic one. Any important disease, whose physical etiology is not understood, and for which treatment is ineffectual, tends to be awash in significance. First, the subjects of deepest dread (corruption, decay, pollution, anomie, weakness) are identified with the disease. The disease itself becomes a metaphor. Then, in the name of the disease (that is, using it as a metaphor), that horror is imposed on other things. The disease becomes adjectival. Something is said to be disease-like, meaning that it is disgusting or ugly. In French, a crumbling stone façade is still “lépreuse.”