Sidney Perkowitz in Nautilus:

Chances are, you’re hunkered down at home right now, as I am, worried about COVID-19 and coping by means of Instacart deliveries, Zoom chats, and Netflix movies, while avoiding others and the outside world. As shown by the experience in China1 and recent studies,2 voluntary isolation to extreme lockdown are effective in slowing or stopping pandemics. But as cabin fever sets in and we miss friends and family, it’s natural to wonder about the mental and social cost of widespread physical separation. Yet the surprising fact is your tech-heavy exile is not a brand new idea in the Internet Age. It was foreseen long ago. The prophet was the great English novelist E.M. Forster. His literary classics Howards End, about British social relationships in Edwardian times, and A Passage to India, about British rule in India, are also known through their masterly film versions.

Chances are, you’re hunkered down at home right now, as I am, worried about COVID-19 and coping by means of Instacart deliveries, Zoom chats, and Netflix movies, while avoiding others and the outside world. As shown by the experience in China1 and recent studies,2 voluntary isolation to extreme lockdown are effective in slowing or stopping pandemics. But as cabin fever sets in and we miss friends and family, it’s natural to wonder about the mental and social cost of widespread physical separation. Yet the surprising fact is your tech-heavy exile is not a brand new idea in the Internet Age. It was foreseen long ago. The prophet was the great English novelist E.M. Forster. His literary classics Howards End, about British social relationships in Edwardian times, and A Passage to India, about British rule in India, are also known through their masterly film versions.

Howards End is the origin of Forster’s famous catchphrase, “Only connect!,” expressing his belief in the essential need for human relationships. Protecting those connections in an increasingly mechanized world was the theme of Forster’s 1909 story, “The Machine Stops.” The science-fiction story is a protest against what Forster saw as the dehumanizing effects of technology. It is meant to be a counterweight to H.G. Wells’ faith in the value of scientific and technological progress. Forster was firmly on the humanities side of the Two Cultures, the other being science, delineated by another English novelist, C.P. Snow, in the 1950s. But time and progress have a funny way of reshaping literature. Today “The Machine Stops” can be read as a remarkably prescient depiction of the Internet. What’s more, Forster might be astonished to learn his Machine can draw us together and preserve our humanity and relationships. That’s not to say, however, that a warning about technology in “The Machine Stops” doesn’t linger.

More here.

In the third week of February, as the

In the third week of February, as the  A global pandemic of this scale was inevitable. In recent years, hundreds of health experts have written books, white papers, and op-eds warning of the possibility. Bill Gates has been telling anyone who would listen, including the

A global pandemic of this scale was inevitable. In recent years, hundreds of health experts have written books, white papers, and op-eds warning of the possibility. Bill Gates has been telling anyone who would listen, including the  As the coronavirus outbreak in the US follows the same grim exponential growth path first displayed in Wuhan, China, before herculean measures were put in place to slow its spread there, America is waking up to the fact that it has almost no public capacity to deal with it.

As the coronavirus outbreak in the US follows the same grim exponential growth path first displayed in Wuhan, China, before herculean measures were put in place to slow its spread there, America is waking up to the fact that it has almost no public capacity to deal with it. The first big need is medical supplies, facilities and personnel. That is why we need to finance immediate domestic production of masks, oxygen tanks, ventilators and the construction and staffing of field hospitals, including the conversion of existing structures such as hotels, dormitories and stadiums, and the hiring and upgrading of staff.

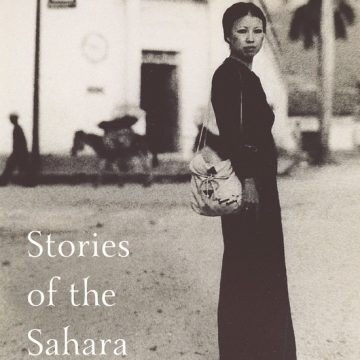

The first big need is medical supplies, facilities and personnel. That is why we need to finance immediate domestic production of masks, oxygen tanks, ventilators and the construction and staffing of field hospitals, including the conversion of existing structures such as hotels, dormitories and stadiums, and the hiring and upgrading of staff. As I read, I kept wondering why Sanmao’s persona was so magnetic. Is it simply because she was so unusual, out there in the vast and largely unpeopled desert, likely the only Taiwanese woman for miles around? Part of the draw of Stories of the Sahara is that it promises to satisfy our curiosity—what was she even doing there? But I couldn’t shake a sense of vertigo. I learned of Sanmao’s existence recently, through a teacher who had in turn learned about her from an article in the New York Times. And yet: “Of course we know who Sanmao is,” my parents told me over the phone. They grew up in Taiwan in the 1970s; they were in college when Sanmao began publishing her Saharan dispatches. One of my mom’s go-to karaoke songs is “The Olive Tree”—Sanmao wrote the lyrics. (“Don’t ask from where I have come / My home is far, far away.”) Who was this person, whose stories had traveled—across far-flung borders and multiple language barriers—from my parents’ lives into my own?

As I read, I kept wondering why Sanmao’s persona was so magnetic. Is it simply because she was so unusual, out there in the vast and largely unpeopled desert, likely the only Taiwanese woman for miles around? Part of the draw of Stories of the Sahara is that it promises to satisfy our curiosity—what was she even doing there? But I couldn’t shake a sense of vertigo. I learned of Sanmao’s existence recently, through a teacher who had in turn learned about her from an article in the New York Times. And yet: “Of course we know who Sanmao is,” my parents told me over the phone. They grew up in Taiwan in the 1970s; they were in college when Sanmao began publishing her Saharan dispatches. One of my mom’s go-to karaoke songs is “The Olive Tree”—Sanmao wrote the lyrics. (“Don’t ask from where I have come / My home is far, far away.”) Who was this person, whose stories had traveled—across far-flung borders and multiple language barriers—from my parents’ lives into my own? The Telegraph has branded the monkey-puzzle a “love-it-or-loathe-it tree.” Tony Kirkham, Head of the Arboretum, Gardens, and Horticultural Services at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew confirmed as much by phone: “Mhm. We call it the Marmite Tree.” Whether you go for the monkey-puzzle depends on how you feel about a Tim Burton cover of Dr. Seuss’s Truffula. Its spiraling leaves are as sharp as shivs, and some people effuse that the species is a “fantastic product.” “It’s one of those few trees that you can’t climb,” Kirkham noted. (You certainly cannot hug it.) He thinks the tree is grand, and when I mentioned monkey-puzzles to my friend Mitch Owens, AD’s decorative arts editor, Owens told me, “I adore them.” Others report back on the boughs as “savage curlicues,” “a nightmare to work in and around.” On a plant that can reach 160 feet and live 2,000 years, those branches hold forth like topiarian antenna, sending/receiving who knows what to/from who knows what galaxy.

The Telegraph has branded the monkey-puzzle a “love-it-or-loathe-it tree.” Tony Kirkham, Head of the Arboretum, Gardens, and Horticultural Services at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew confirmed as much by phone: “Mhm. We call it the Marmite Tree.” Whether you go for the monkey-puzzle depends on how you feel about a Tim Burton cover of Dr. Seuss’s Truffula. Its spiraling leaves are as sharp as shivs, and some people effuse that the species is a “fantastic product.” “It’s one of those few trees that you can’t climb,” Kirkham noted. (You certainly cannot hug it.) He thinks the tree is grand, and when I mentioned monkey-puzzles to my friend Mitch Owens, AD’s decorative arts editor, Owens told me, “I adore them.” Others report back on the boughs as “savage curlicues,” “a nightmare to work in and around.” On a plant that can reach 160 feet and live 2,000 years, those branches hold forth like topiarian antenna, sending/receiving who knows what to/from who knows what galaxy. The cumulative strength of the New Narrative, which consisted of a core group of writers who took government-funded workshops run by Glück and the similarly under-sung Bruce Boone as well as some kindred, famous spirits far from Northern California—Kathy Acker, Dennis Cooper, Gary Indiana, and Chris Kraus—ensured that Glück’s name has remained in certain corners of the American literary edifice over the past few decades. Yet time and a shifting sensibility has relegated his own fiction to creaky personal libraries such as my own. I crack open original editions of Jack the Modernist and Margery Kempe and see the names of lost, idealistic imprints, SeaHorse and High Risk Books, which went down with the sinking ship of American publishing while larger houses bought space on the lifeboats. The paper trail of gay literature—put out by presses little and big—is inherently splotchy: so many people who had reason to remember died of AIDS.

The cumulative strength of the New Narrative, which consisted of a core group of writers who took government-funded workshops run by Glück and the similarly under-sung Bruce Boone as well as some kindred, famous spirits far from Northern California—Kathy Acker, Dennis Cooper, Gary Indiana, and Chris Kraus—ensured that Glück’s name has remained in certain corners of the American literary edifice over the past few decades. Yet time and a shifting sensibility has relegated his own fiction to creaky personal libraries such as my own. I crack open original editions of Jack the Modernist and Margery Kempe and see the names of lost, idealistic imprints, SeaHorse and High Risk Books, which went down with the sinking ship of American publishing while larger houses bought space on the lifeboats. The paper trail of gay literature—put out by presses little and big—is inherently splotchy: so many people who had reason to remember died of AIDS. It is not surprising to find Rusty Reno, editor of First Things,

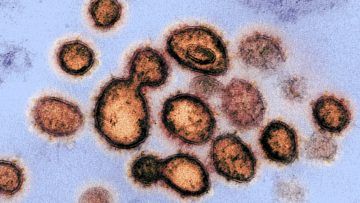

It is not surprising to find Rusty Reno, editor of First Things,  Drugs that slow or kill the novel coronavirus, called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), could save the lives of severely ill patients, but might also be given prophylactically to protect health care workers and others at high risk of infection. Treatments may also reduce the time patients spend in intensive care units, freeing critical hospital beds. Scientists have suggested dozens of existing compounds for testing, but WHO is focusing on what it says are the four most promising therapies: an experimental antiviral compound called remdesivir; the malaria medications chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine; a combination of two HIV drugs, lopinavir and ritonavir; and that same combination plus interferon-beta, an immune system messenger that can help cripple viruses. Some data on their use in COVID-19 patients have already emerged—the HIV combo failed in a small study in China—but WHO believes a large trial with a greater variety of patients is warranted.

Drugs that slow or kill the novel coronavirus, called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), could save the lives of severely ill patients, but might also be given prophylactically to protect health care workers and others at high risk of infection. Treatments may also reduce the time patients spend in intensive care units, freeing critical hospital beds. Scientists have suggested dozens of existing compounds for testing, but WHO is focusing on what it says are the four most promising therapies: an experimental antiviral compound called remdesivir; the malaria medications chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine; a combination of two HIV drugs, lopinavir and ritonavir; and that same combination plus interferon-beta, an immune system messenger that can help cripple viruses. Some data on their use in COVID-19 patients have already emerged—the HIV combo failed in a small study in China—but WHO believes a large trial with a greater variety of patients is warranted. Though mild, I have what I am fairly sure are the symptoms of coronavirus. Three weeks ago I was in extended and close contact with someone who has since tested positive. When I learned this, I spent some time trying to figure out how to get tested myself, but now the last thing I want to do is to go stand in a line in front of a Brooklyn hospital along with others who also have symptoms. My wife and I have not been outside our apartment since March 10th. We have opened the door just three times since then, to receive groceries that had been left for us by an unseen deliveryman, as per our instructions, on the other side. We read of others going on walks, but that seems like a selfish extravagance when you have a dry cough and a sore throat. This is the smallest apartment I’ve ever lived in. I am noticing features of it, and of the trees, the sky and the light outside our windows, that escaped my attention—shamefully, it now seems—over the first several months since we arrived here in August. I know when we finally get out I will be like the protagonist of Halldór Laxness’s stunning novel, World Light, who, after years of bedridden illness, weeps when he bids farewell to all the knots and grooves in the wood beams of his attic ceiling.

Though mild, I have what I am fairly sure are the symptoms of coronavirus. Three weeks ago I was in extended and close contact with someone who has since tested positive. When I learned this, I spent some time trying to figure out how to get tested myself, but now the last thing I want to do is to go stand in a line in front of a Brooklyn hospital along with others who also have symptoms. My wife and I have not been outside our apartment since March 10th. We have opened the door just three times since then, to receive groceries that had been left for us by an unseen deliveryman, as per our instructions, on the other side. We read of others going on walks, but that seems like a selfish extravagance when you have a dry cough and a sore throat. This is the smallest apartment I’ve ever lived in. I am noticing features of it, and of the trees, the sky and the light outside our windows, that escaped my attention—shamefully, it now seems—over the first several months since we arrived here in August. I know when we finally get out I will be like the protagonist of Halldór Laxness’s stunning novel, World Light, who, after years of bedridden illness, weeps when he bids farewell to all the knots and grooves in the wood beams of his attic ceiling. I had a bone marrow transplant in 2017. Most people don’t really know what that is. In the simplest possible terms, it means that my doctors gave me a new immune system, by replacing my sick bone marrow with healthy bone marrow from my sister.

I had a bone marrow transplant in 2017. Most people don’t really know what that is. In the simplest possible terms, it means that my doctors gave me a new immune system, by replacing my sick bone marrow with healthy bone marrow from my sister. Bill Gates rebuked proposals, floated over the last two days by leaders like Donald Trump, to reopen the global economy despite

Bill Gates rebuked proposals, floated over the last two days by leaders like Donald Trump, to reopen the global economy despite  It happened slowly and then suddenly. On Monday, March 9th, the spectre of a pandemic in New York was still off on the puzzling horizon. By Friday, it was the dominant fact of life. New Yorkers began to adopt a grim new dance of “social distancing.” On a sparsely peopled 5 train, heading down to Grand Central Terminal on Saturday morning, passengers warily tried to achieve an even, strategic spacing, like chess pieces during an endgame: the rook all the way down here, but threatening the king from the back row. Then, when the doors opened, they got off the train one by one, in single, hesitant file, unlearning in a minute New York habits ingrained over lifetimes, the elbowed rush for the door. In the relatively empty subway cars, one can focus on the human details of the riders. A. J. Liebling, in a piece published in these pages some sixty years ago, recounted the tale of a once famous New York murder, in which the headless torso of a man was found wrapped in oilcloth, floating in the East River. The hero of the tale, as Liebling chose to tell it, was a young reporter for the great New York World, who identified the body by type before anyone else did: he saw that the corpse’s fingertips were wrinkled in a way that characterized “rubbers”—masseurs—in Turkish baths. Only someone whose hands were wet that often would have those fingertips. On the subway, in the street, nearly everyone has rubbers’ hands now, with skin shrivelled from excessive washing.

It happened slowly and then suddenly. On Monday, March 9th, the spectre of a pandemic in New York was still off on the puzzling horizon. By Friday, it was the dominant fact of life. New Yorkers began to adopt a grim new dance of “social distancing.” On a sparsely peopled 5 train, heading down to Grand Central Terminal on Saturday morning, passengers warily tried to achieve an even, strategic spacing, like chess pieces during an endgame: the rook all the way down here, but threatening the king from the back row. Then, when the doors opened, they got off the train one by one, in single, hesitant file, unlearning in a minute New York habits ingrained over lifetimes, the elbowed rush for the door. In the relatively empty subway cars, one can focus on the human details of the riders. A. J. Liebling, in a piece published in these pages some sixty years ago, recounted the tale of a once famous New York murder, in which the headless torso of a man was found wrapped in oilcloth, floating in the East River. The hero of the tale, as Liebling chose to tell it, was a young reporter for the great New York World, who identified the body by type before anyone else did: he saw that the corpse’s fingertips were wrinkled in a way that characterized “rubbers”—masseurs—in Turkish baths. Only someone whose hands were wet that often would have those fingertips. On the subway, in the street, nearly everyone has rubbers’ hands now, with skin shrivelled from excessive washing.