Jake Wojtowicz in Aeon:

Jake Wojtowicz in Aeon:

For better or for worse, luck can sweep in from nowhere and alter our lives. You might cross the road and get hit by a car, or you might end up bumping into someone who turns out to be the love of your life. One natural way of thinking about luck is that it happens to us. Things – unexpected and uncontrolled things – happen to us.

What happens to us naturally contrasts with what we do. But, in his paper ‘Moral Luck’ (1981), the British philosopher Bernard Williams conjures the example of a lorry driver who hits and kills a child. The driver didn’t kill the child due to being drunk or driving carelessly. He was just unlucky. In such a case, as Williams later put it in his book Shame and Necessity (1993): ‘The terrible thing that happened to him, through no fault of his own, was that he did those things.’ He hit and killed the child. Luck can do more than just happen to us; it can affect what we do. Or, to put it another way: what we do is not fully in our control.

Williams gave a name to an emotion that can accompany doing bad things through bad luck: agent-regret. This is different from remorse, which Williams linked to doing bad things voluntarily. The driver’s tragedy isn’t that he was speeding or driving carelessly – voluntary things that might arouse remorse; his tragedy is simply that he killed someone.

More here.

Christopher Mackin in TNR:

Christopher Mackin in TNR: David Runciman in The Guardian:

David Runciman in The Guardian:

People around the world are processing the news that the revered spiritual leader

People around the world are processing the news that the revered spiritual leader  LIKE MARTHA NUSSBAUM’S other books, The Cosmopolitan Tradition is a profound and insightful interrogation of central issues in philosophy and our everyday lives. Nussbaum’s newest contribution analyzes the “Cosmopolitan tradition” — that is, the view that we are citizens of the world who enjoy the equal and unconditional worth of all human beings. This worth is independent of people’s individual traits, which depend on fortuitous natural or social arrangements. As Nussbaum claims, the “insight that politics ought to treat human beings both as equal and as having a worth beyond price is one of the deepest and most influential insights of Western thought.” She further argues that, in this tradition, dignity — the right of a person to be treated respectfully for her own sake — is non-hierarchical. It belongs, in equal measure, to all who have some basic threshold capacity for moral learning and choice. Nussbaum persuasively argues that the major flaw of this noble idea is the bifurcation between duties of justice, on the one hand, and duties of material expenditure, on the other.

LIKE MARTHA NUSSBAUM’S other books, The Cosmopolitan Tradition is a profound and insightful interrogation of central issues in philosophy and our everyday lives. Nussbaum’s newest contribution analyzes the “Cosmopolitan tradition” — that is, the view that we are citizens of the world who enjoy the equal and unconditional worth of all human beings. This worth is independent of people’s individual traits, which depend on fortuitous natural or social arrangements. As Nussbaum claims, the “insight that politics ought to treat human beings both as equal and as having a worth beyond price is one of the deepest and most influential insights of Western thought.” She further argues that, in this tradition, dignity — the right of a person to be treated respectfully for her own sake — is non-hierarchical. It belongs, in equal measure, to all who have some basic threshold capacity for moral learning and choice. Nussbaum persuasively argues that the major flaw of this noble idea is the bifurcation between duties of justice, on the one hand, and duties of material expenditure, on the other. There is a box in my apartment labeled “Old Not Good Photos.” This is an understatement. Most of the photos are two-and-a-half-inch squares, showing little blurred black-and-white images, taken from too far away of people whose features you can barely make out, standing or sitting alone or in groups, against backgrounds of gray uninterestingness. They are like the barely flickering dreams that dissipate as we awaken, rather than the self-important ones that follow us into the day and seem to be crying out for interpretation. However, as psychoanalysis has taught us, it is the least prepossessing dreams, disguised as such to put us off the scent, that sometimes bear the most important messages from inner life. So too, some of the drab little photographs, if stared at long enough, begin to speak to us.

There is a box in my apartment labeled “Old Not Good Photos.” This is an understatement. Most of the photos are two-and-a-half-inch squares, showing little blurred black-and-white images, taken from too far away of people whose features you can barely make out, standing or sitting alone or in groups, against backgrounds of gray uninterestingness. They are like the barely flickering dreams that dissipate as we awaken, rather than the self-important ones that follow us into the day and seem to be crying out for interpretation. However, as psychoanalysis has taught us, it is the least prepossessing dreams, disguised as such to put us off the scent, that sometimes bear the most important messages from inner life. So too, some of the drab little photographs, if stared at long enough, begin to speak to us. On 29 August 1966, the Beatles closed their set at the Candlestick Park baseball stadium in San Francisco with “Long Tall Sally”, an old Little Richard number that had been part of their repertoire from the very start. “See you again next year,” said John as they left the stage. The group then clambered into an armoured car and were driven away. It was to be their last proper concert. Their American tour had been exhausting, sporadically frightening, and unrewarding. By this stage their delight in their own fame had worn off. They were fed up with all the hassle of touring, and tired of the way the screaming continued to drown out the music, so that even they were unable to hear it. Having been shepherded into an empty, windowless truck after a particularly miserable show in a rainy St Louis, Paul said to the others: “I really fucking agree with you. I’ve fucking had it up to here too.”

On 29 August 1966, the Beatles closed their set at the Candlestick Park baseball stadium in San Francisco with “Long Tall Sally”, an old Little Richard number that had been part of their repertoire from the very start. “See you again next year,” said John as they left the stage. The group then clambered into an armoured car and were driven away. It was to be their last proper concert. Their American tour had been exhausting, sporadically frightening, and unrewarding. By this stage their delight in their own fame had worn off. They were fed up with all the hassle of touring, and tired of the way the screaming continued to drown out the music, so that even they were unable to hear it. Having been shepherded into an empty, windowless truck after a particularly miserable show in a rainy St Louis, Paul said to the others: “I really fucking agree with you. I’ve fucking had it up to here too.” On the final page of “MBS,” his detailed and disturbing portrait of Saudi Arabia’s crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, Ben Hubbard admits that, given what he learned in the course of his reporting on the kingdom’s de facto ruler and the ways his ruthless minions have pursued their boss’s perceived enemies, he “did wonder, while walking home late at night or drifting off to sleep, whether they might come after me as well.” Perhaps that sounds melodramatic, but anyone who reads Hubbard’s clear and convincing narrative will find the concern all too plausible. And where could you turn if the prince did lash out? Certainly not to an American administration that believed M.B.S. ordered the 2018 murder and dismemberment of the Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi but gave the prince a pass. “

On the final page of “MBS,” his detailed and disturbing portrait of Saudi Arabia’s crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, Ben Hubbard admits that, given what he learned in the course of his reporting on the kingdom’s de facto ruler and the ways his ruthless minions have pursued their boss’s perceived enemies, he “did wonder, while walking home late at night or drifting off to sleep, whether they might come after me as well.” Perhaps that sounds melodramatic, but anyone who reads Hubbard’s clear and convincing narrative will find the concern all too plausible. And where could you turn if the prince did lash out? Certainly not to an American administration that believed M.B.S. ordered the 2018 murder and dismemberment of the Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi but gave the prince a pass. “ “

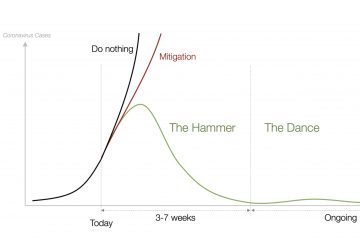

“ Summary of the article: Strong coronavirus measures today should only last a few weeks, there shouldn’t be a big peak of infections afterwards, and it can all be done for a reasonable cost to society, saving millions of lives along the way. If we don’t take these measures, tens of millions will be infected, many will die, along with anybody else that requires intensive care, because the healthcare system will have collapsed.

Summary of the article: Strong coronavirus measures today should only last a few weeks, there shouldn’t be a big peak of infections afterwards, and it can all be done for a reasonable cost to society, saving millions of lives along the way. If we don’t take these measures, tens of millions will be infected, many will die, along with anybody else that requires intensive care, because the healthcare system will have collapsed. How long is this going to last? As terrible as a pandemic would be, is averting it really worth a new Great Depression? What is the endgame?

How long is this going to last? As terrible as a pandemic would be, is averting it really worth a new Great Depression? What is the endgame? For an immeasurable public health disaster, Washington has come up with unheard of relief, about double what the federal government budgets for all spending in a whole year. And the case loads and death toll of the coronavirus keep rising, unevenly, unpredictably, and by far the worst in New York, city and state. Mark Blyth is our almost reflexive call: our political economist at Brown University, eagle-eyed and irreverent on those places where money and power mix and mingle and make rules for the world. He can sound like the noisiest know-it-all in a Glasgow pub, but people always say he has a gift for making sense where they hadn’t seen it.

For an immeasurable public health disaster, Washington has come up with unheard of relief, about double what the federal government budgets for all spending in a whole year. And the case loads and death toll of the coronavirus keep rising, unevenly, unpredictably, and by far the worst in New York, city and state. Mark Blyth is our almost reflexive call: our political economist at Brown University, eagle-eyed and irreverent on those places where money and power mix and mingle and make rules for the world. He can sound like the noisiest know-it-all in a Glasgow pub, but people always say he has a gift for making sense where they hadn’t seen it. Gwendolyn Brooks grew up on Chicago’s South Side in a house her father bought shortly after the poet and her younger brother were born. Located at 4332 South Champlain, it was a comfortable home with a large front porch and backyard. The Brooks family was only the second black family on the block, but as the 1920s slid into the 1930s, African Americans began to move to the area in increasing numbers. Once a “Black Belt” was recognized, a series of discriminatory housing practices started: Chicago’s growing African American population was soon unofficially segregated. The narrow corridor of apartment buildings and houses along State Street could not hope to hold the explosion of skilled and unskilled workers who moved to the city during World War II; one solution was to chop existing houses and apartments into ever smaller units, called “kitchenettes.” These single rooms or series of small rooms, often rented at high profit by predatory landlords, housed entire families who shared kitchens, bathrooms, and much else. They were cramped microcosms of the circumscribed lives endured by most African Americans at the time.

Gwendolyn Brooks grew up on Chicago’s South Side in a house her father bought shortly after the poet and her younger brother were born. Located at 4332 South Champlain, it was a comfortable home with a large front porch and backyard. The Brooks family was only the second black family on the block, but as the 1920s slid into the 1930s, African Americans began to move to the area in increasing numbers. Once a “Black Belt” was recognized, a series of discriminatory housing practices started: Chicago’s growing African American population was soon unofficially segregated. The narrow corridor of apartment buildings and houses along State Street could not hope to hold the explosion of skilled and unskilled workers who moved to the city during World War II; one solution was to chop existing houses and apartments into ever smaller units, called “kitchenettes.” These single rooms or series of small rooms, often rented at high profit by predatory landlords, housed entire families who shared kitchens, bathrooms, and much else. They were cramped microcosms of the circumscribed lives endured by most African Americans at the time. These days, the singer-songwriter, who is forty-two, rarely leaves her tranquil house, in Venice Beach, other than to take early-morning walks on the beach with Mercy. Five years ago, Apple stopped going to Largo, the Los Angeles venue where, since the late nineties, she’d regularly performed her thorny, emotionally revelatory songs. (Her song “Largo” still plays on the club’s Web site.) She’d cancelled her most recent tour, in 2012, when Janet, a pit bull she had adopted when she was twenty-two, was dying. Still, a lot can go on without leaving home. Apple’s new album, whose completion she’d been inching toward for years, was a tricky topic, and so, during the week that I visited, we cycled in and out of other subjects, among them her decision, a year earlier, to stop drinking; estrangements from old friends; and her memories of growing up, in Manhattan, as the youngest child in the “second family” of a married Broadway actor. Near the front door of Apple’s house stood a chalkboard on wheels, which was scrawled with the title of the upcoming album: “Fetch the Bolt Cutters.”

These days, the singer-songwriter, who is forty-two, rarely leaves her tranquil house, in Venice Beach, other than to take early-morning walks on the beach with Mercy. Five years ago, Apple stopped going to Largo, the Los Angeles venue where, since the late nineties, she’d regularly performed her thorny, emotionally revelatory songs. (Her song “Largo” still plays on the club’s Web site.) She’d cancelled her most recent tour, in 2012, when Janet, a pit bull she had adopted when she was twenty-two, was dying. Still, a lot can go on without leaving home. Apple’s new album, whose completion she’d been inching toward for years, was a tricky topic, and so, during the week that I visited, we cycled in and out of other subjects, among them her decision, a year earlier, to stop drinking; estrangements from old friends; and her memories of growing up, in Manhattan, as the youngest child in the “second family” of a married Broadway actor. Near the front door of Apple’s house stood a chalkboard on wheels, which was scrawled with the title of the upcoming album: “Fetch the Bolt Cutters.” Huysmans reviewed the Salons of 1879-82 and the Independent Exhibitions of 1880-82 at considerable length. His articles, collected as L’Art moderne (1883), have never before been translated into English, probably because he is the least known of the writer-critics, and his French is often not straightforward. Robert Baldick, biographer of Huysmans (1955) and translator of his most famous novel, À Rebours, described his style as ‘one of the strangest literary idioms in existence’. Léon Bloy, a fellow writer and fellow Catholic, described it as ‘continually dragging Mother Image by the hair or the feet down the wormeaten staircase of terrified Syntax’. Brendan King, who has already translated most of Huysmans’s fiction, has produced an excellent version. Rarely can it have been such fun to read translated denunciations of so many forgotten French pictures. The edition also includes scores of small black and white illustrations, which can easily be Googled into colour.

Huysmans reviewed the Salons of 1879-82 and the Independent Exhibitions of 1880-82 at considerable length. His articles, collected as L’Art moderne (1883), have never before been translated into English, probably because he is the least known of the writer-critics, and his French is often not straightforward. Robert Baldick, biographer of Huysmans (1955) and translator of his most famous novel, À Rebours, described his style as ‘one of the strangest literary idioms in existence’. Léon Bloy, a fellow writer and fellow Catholic, described it as ‘continually dragging Mother Image by the hair or the feet down the wormeaten staircase of terrified Syntax’. Brendan King, who has already translated most of Huysmans’s fiction, has produced an excellent version. Rarely can it have been such fun to read translated denunciations of so many forgotten French pictures. The edition also includes scores of small black and white illustrations, which can easily be Googled into colour.