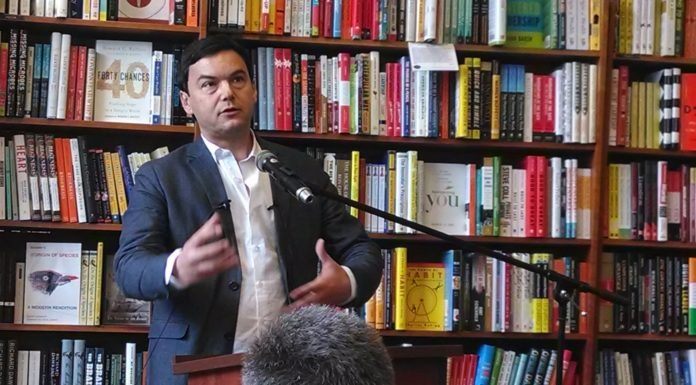

Asher Schechter in Pro-Market:

Inequality is neither economic nor technological; it is ideological and political.” Thomas Piketty’s latest book, Capital and Ideology, is a 1200-page tome chock-full of facts, figures, policy proposals, and digressions that defies easy categorization, but its main argument can be best summed up by its opening line. Piketty’s latest is the long-anticipated follow-up to his bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which became an unexpected cultural phenomenon when its English translation came out in 2014. It is twice as long and much broader in scope, providing a sweeping historical overview of how inequality has been driven and reinforced by ideological and political decisions throughout history.

Inequality is neither economic nor technological; it is ideological and political.” Thomas Piketty’s latest book, Capital and Ideology, is a 1200-page tome chock-full of facts, figures, policy proposals, and digressions that defies easy categorization, but its main argument can be best summed up by its opening line. Piketty’s latest is the long-anticipated follow-up to his bestseller Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which became an unexpected cultural phenomenon when its English translation came out in 2014. It is twice as long and much broader in scope, providing a sweeping historical overview of how inequality has been driven and reinforced by ideological and political decisions throughout history.

It is a startlingly ambitious book, even more so than its predecessor. Whereas Capital in the Twenty-First Century was firmly rooted in economics, Capital and Ideology’s overarching thesis draws on political science, history, and sociology. It is also, surprisingly, rather optimistic, as Piketty explores various historical examples to establish his argument that extreme inequality is not preordained.

More here.

How will we live, or be forced to live, after the pandemic? “I don’t know” is—

How will we live, or be forced to live, after the pandemic? “I don’t know” is— Recently, the Federal Reserve announced that it would be loosening its lending guidelines so that more corporations, even those with massive pre-existing debts, could take part in the bailout feeding frenzy.

Recently, the Federal Reserve announced that it would be loosening its lending guidelines so that more corporations, even those with massive pre-existing debts, could take part in the bailout feeding frenzy.  On a freezing December day in 1386, at an old priory in Paris that today is a museum of science and technology—a temple of human reason—an eager crowd of thousands gathered to watch two knights fight a duel to the death with lance and sword and dagger. A beautiful young noblewoman, dressed all in black and exposed to the crowd’s stares, anxiously awaited the outcome. The trial by combat would decide whether she had told the truth—and thus whether she would live or die. Like today, sexual assault and rape often went unpunished and even unreported in the Middle Ages. But a public accusation of rape, at the time a capital offense and often a cause for scandalous rumors endangering the honor of those involved, could have grave consequences for both accuser and accused, especially among the nobility.

On a freezing December day in 1386, at an old priory in Paris that today is a museum of science and technology—a temple of human reason—an eager crowd of thousands gathered to watch two knights fight a duel to the death with lance and sword and dagger. A beautiful young noblewoman, dressed all in black and exposed to the crowd’s stares, anxiously awaited the outcome. The trial by combat would decide whether she had told the truth—and thus whether she would live or die. Like today, sexual assault and rape often went unpunished and even unreported in the Middle Ages. But a public accusation of rape, at the time a capital offense and often a cause for scandalous rumors endangering the honor of those involved, could have grave consequences for both accuser and accused, especially among the nobility. Catherine the Great is a monarch mired in misconception. Derided both in her day and in modern times as a hypocritical warmonger with an unnatural sexual appetite, Catherine was a woman of contradictions whose brazen exploits have long overshadowed the accomplishments that won her “the Great” moniker in the first place.

Catherine the Great is a monarch mired in misconception. Derided both in her day and in modern times as a hypocritical warmonger with an unnatural sexual appetite, Catherine was a woman of contradictions whose brazen exploits have long overshadowed the accomplishments that won her “the Great” moniker in the first place. Beginning thousands of years before the first dairy restaurant appeared, Katchor’s book attempts to explicate the laws of kashruth—the separation of milk and meat—and other dietary notions and origin myths. (The mixture of causal logic and total irrationality recalls Katchor’s musical-theater piece The Slug Bearers of Kayrol Island, in which exploited workers transport tiny lead weights to place inside and give heft to small appliances.) Coffeehouse culture stimulates the Enlightenment. Radical puritans imagine a prelapsarian Hebrew vegetarian diet while, having internalized certain liberal values advanced by the French Revolution, eighteenth-century Parisians invent the “restaurant” and the “menu,” consecrated to individual rights and freedom of choice.

Beginning thousands of years before the first dairy restaurant appeared, Katchor’s book attempts to explicate the laws of kashruth—the separation of milk and meat—and other dietary notions and origin myths. (The mixture of causal logic and total irrationality recalls Katchor’s musical-theater piece The Slug Bearers of Kayrol Island, in which exploited workers transport tiny lead weights to place inside and give heft to small appliances.) Coffeehouse culture stimulates the Enlightenment. Radical puritans imagine a prelapsarian Hebrew vegetarian diet while, having internalized certain liberal values advanced by the French Revolution, eighteenth-century Parisians invent the “restaurant” and the “menu,” consecrated to individual rights and freedom of choice. What is it you see, asks Rachael Z. DeLue, in Romare Bearden’s artwork? Why is it you just can’t stop looking? How is it they remain, decades after his death, sources of what Wallace Stevens calls “imperishable bliss”?

What is it you see, asks Rachael Z. DeLue, in Romare Bearden’s artwork? Why is it you just can’t stop looking? How is it they remain, decades after his death, sources of what Wallace Stevens calls “imperishable bliss”? When I was a kid, I adored going over to my grandmother’s house and exploring her art room. To reach it, I wound past my grandmother’s collections of things in the living room and hall, most in service of her

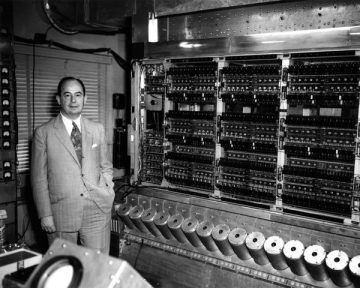

When I was a kid, I adored going over to my grandmother’s house and exploring her art room. To reach it, I wound past my grandmother’s collections of things in the living room and hall, most in service of her  That John von Neumann was one of the supreme intellects humanity has produced should be a statement beyond dispute. Both the lightning fast speed of his mind and the astonishing range of fields he made seminal contributions to made him a legend in his own lifetime. When he died in 1957 at the young age of 56 it was a huge loss; the loss of a great mathematician, a great polymath and to many, a great patriotic American who had done much to improve his country’s advantage in cutting-edge weaponry.

That John von Neumann was one of the supreme intellects humanity has produced should be a statement beyond dispute. Both the lightning fast speed of his mind and the astonishing range of fields he made seminal contributions to made him a legend in his own lifetime. When he died in 1957 at the young age of 56 it was a huge loss; the loss of a great mathematician, a great polymath and to many, a great patriotic American who had done much to improve his country’s advantage in cutting-edge weaponry. INDIAN CINEMA LOVES LOVE.

INDIAN CINEMA LOVES LOVE. If anybody profited from the war, it was us: its children. Apart from having survived it, we were richly provided with stuff to romanticize or to fantasize about. In addition to the usual childhood diet of Dumas and Jules Verne, we had military paraphernalia, which always goes well with boys. With us, it went exceptionally well, since it was our country that won the war.

If anybody profited from the war, it was us: its children. Apart from having survived it, we were richly provided with stuff to romanticize or to fantasize about. In addition to the usual childhood diet of Dumas and Jules Verne, we had military paraphernalia, which always goes well with boys. With us, it went exceptionally well, since it was our country that won the war.

As scientists work to create a vaccine against COVID-19, a small but fervent anti-vaccination movement is marshalling against it. Campaigners are seeding outlandish narratives: they falsely say that coronavirus vaccines will be used to implant microchips into people, for instance, and falsely claim that a woman who took part in a UK vaccine trial died. In April, some carried placards with anti-vaccine slogans at rallies in California to protest against the lockdown. Last week, a now-deleted YouTube video promoting wild conspiracy theories about the pandemic and asserting (without evidence) that vaccines would “kill millions” received more than 8 million views.

As scientists work to create a vaccine against COVID-19, a small but fervent anti-vaccination movement is marshalling against it. Campaigners are seeding outlandish narratives: they falsely say that coronavirus vaccines will be used to implant microchips into people, for instance, and falsely claim that a woman who took part in a UK vaccine trial died. In April, some carried placards with anti-vaccine slogans at rallies in California to protest against the lockdown. Last week, a now-deleted YouTube video promoting wild conspiracy theories about the pandemic and asserting (without evidence) that vaccines would “kill millions” received more than 8 million views. When Dwight D. Eisenhower was planning the invasion of Normandy, he made sure to check with Walter Munk and his colleagues first. Munk had come to the United States from Austria-Hungary to work as a banker before switching to oceanography, eventually making major advances in the science of tidal and wave forecasting. He was a defense researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in 1944 when his team calculated that the seas on June 5 of that year would be so rough that a delay was in order. The invasion would happen on the following day.

When Dwight D. Eisenhower was planning the invasion of Normandy, he made sure to check with Walter Munk and his colleagues first. Munk had come to the United States from Austria-Hungary to work as a banker before switching to oceanography, eventually making major advances in the science of tidal and wave forecasting. He was a defense researcher at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in 1944 when his team calculated that the seas on June 5 of that year would be so rough that a delay was in order. The invasion would happen on the following day.