Uri Alon, Ron Milo and Eran Yashiv in the New York Times:

If we cannot resume economic activity without causing a resurgence of Covid-19 infections, we face a grim, unpredictable future of opening and closing schools and businesses.

If we cannot resume economic activity without causing a resurgence of Covid-19 infections, we face a grim, unpredictable future of opening and closing schools and businesses.

We can find a way out of this dilemma by exploiting a key property of the virus: its latent period — the three-day delay on average between the time a person is infected and the time he or she can infect others.

People can work in two-week cycles, on the job for four days then, by the time they might become infectious, 10 days at home in lockdown. The strategy works even better when the population is split into two groups of households working alternating weeks.

Austrian school officials will adopt a simple version — with two groups of students attending school for five days every two weeks — starting May 18.

Models we created at the Weizmann Institute in Israel predict that this two-week cycle can reduce the virus’s reproduction number — the average number of people infected by each infected person — below one. So a 10-4 cycle could suppress the epidemic while allowing sustainable economic activity.

More here.

ROBERT BRANDOM IS one of the few living philosophers who can, without exaggeration, be compared to the philosophical giants who once bestrode the earth, or at least loomed large in the study, from the 17th through the 19th centuries: Spinoza, Leibniz, Hume, Kant, Hegel — system-builders who intended to explain all of reality, and ourselves, to ourselves, insofar as we and it were explicable (a matter about which they disagreed). Brandom’s long-awaited book A Spirit of Trust is an achievement in that classical vein, and quite a surprising one in this period of punctilious specialists.

ROBERT BRANDOM IS one of the few living philosophers who can, without exaggeration, be compared to the philosophical giants who once bestrode the earth, or at least loomed large in the study, from the 17th through the 19th centuries: Spinoza, Leibniz, Hume, Kant, Hegel — system-builders who intended to explain all of reality, and ourselves, to ourselves, insofar as we and it were explicable (a matter about which they disagreed). Brandom’s long-awaited book A Spirit of Trust is an achievement in that classical vein, and quite a surprising one in this period of punctilious specialists. It is a challenging time to be 16 and, like his peers, Dara McAnulty must currently endure a form of house arrest that means no seeing friends, no GCSEs. Unlike other locked-down teens, McAnulty is also dealing with the harsh mischance of having his first book, Diary of a Young Naturalist, published during the coronavirus crisis. He was supposed to be touring festivals but every date is cancelled. “I feel like my being is suffering from a slow puncture,” McAnulty tweeted in March. “I honestly feel like my world is falling apart right now.”

It is a challenging time to be 16 and, like his peers, Dara McAnulty must currently endure a form of house arrest that means no seeing friends, no GCSEs. Unlike other locked-down teens, McAnulty is also dealing with the harsh mischance of having his first book, Diary of a Young Naturalist, published during the coronavirus crisis. He was supposed to be touring festivals but every date is cancelled. “I feel like my being is suffering from a slow puncture,” McAnulty tweeted in March. “I honestly feel like my world is falling apart right now.” The people of the Middle East are quite used to the many attempts over decades to reconcile Jews and Arabs. Yet nothing has been tried on such a mass scale as a drama series being shown on one of the Arab world’s most popular TV channels during this year’s month of Ramadan. Since the series began to air in April over the Saudi-backed MBC station, it has dominated viewership ratings at a time when Arab families gather around a television in the evening. The drama “Um Haroun,” or “Mother of Aaron,” centers on a Jewish nurse living in an Arabian Gulf country in the 1940s. She and other Jews live peacefully in a village with Muslims and Christians as she lovingly brings health care to all. While the show has plenty of village intrigue, it depicts interreligious harmony before the 1948 creation of modern Israel and the later rise of intolerant Islamic groups such as Al Qaeda.

The people of the Middle East are quite used to the many attempts over decades to reconcile Jews and Arabs. Yet nothing has been tried on such a mass scale as a drama series being shown on one of the Arab world’s most popular TV channels during this year’s month of Ramadan. Since the series began to air in April over the Saudi-backed MBC station, it has dominated viewership ratings at a time when Arab families gather around a television in the evening. The drama “Um Haroun,” or “Mother of Aaron,” centers on a Jewish nurse living in an Arabian Gulf country in the 1940s. She and other Jews live peacefully in a village with Muslims and Christians as she lovingly brings health care to all. While the show has plenty of village intrigue, it depicts interreligious harmony before the 1948 creation of modern Israel and the later rise of intolerant Islamic groups such as Al Qaeda. If you were an adherent, no one would be able to tell. You would look like any other American. You could be a mother, picking leftovers off your toddler’s plate. You could be the young man in headphones across the street. You could be a bookkeeper, a dentist, a grandmother icing cupcakes in her kitchen. You may well have an affiliation with an evangelical church. But you are hard to identify just from the way you look—which is good, because someday soon dark forces may try to track you down. You understand this sounds crazy, but you don’t care. You know that a small group of manipulators, operating in the shadows, pull the planet’s strings. You know that they are powerful enough to abuse children without fear of retribution. You know that the mainstream media are their handmaidens, in partnership with Hillary Clinton and the secretive denizens of the deep state. You know that only Donald Trump stands between you and a damned and ravaged world. You see plague and pestilence sweeping the planet, and understand that they are part of the plan. You know that a clash between good and evil cannot be avoided, and you yearn for the Great Awakening that is coming. And so you must be on guard at all times. You must shield your ears from the scorn of the ignorant. You must find those who are like you. And you must be prepared to fight.

If you were an adherent, no one would be able to tell. You would look like any other American. You could be a mother, picking leftovers off your toddler’s plate. You could be the young man in headphones across the street. You could be a bookkeeper, a dentist, a grandmother icing cupcakes in her kitchen. You may well have an affiliation with an evangelical church. But you are hard to identify just from the way you look—which is good, because someday soon dark forces may try to track you down. You understand this sounds crazy, but you don’t care. You know that a small group of manipulators, operating in the shadows, pull the planet’s strings. You know that they are powerful enough to abuse children without fear of retribution. You know that the mainstream media are their handmaidens, in partnership with Hillary Clinton and the secretive denizens of the deep state. You know that only Donald Trump stands between you and a damned and ravaged world. You see plague and pestilence sweeping the planet, and understand that they are part of the plan. You know that a clash between good and evil cannot be avoided, and you yearn for the Great Awakening that is coming. And so you must be on guard at all times. You must shield your ears from the scorn of the ignorant. You must find those who are like you. And you must be prepared to fight. Scientists at the University of South Carolina and Columbia University have developed a faster way to design and make gas-filtering membranes that could cut greenhouse gas emissions and reduce pollution. Their new method, published today in Science Advances, mixes machine learning with

Scientists at the University of South Carolina and Columbia University have developed a faster way to design and make gas-filtering membranes that could cut greenhouse gas emissions and reduce pollution. Their new method, published today in Science Advances, mixes machine learning with  According to the government, we are now supposed to be getting back to work. But what does “work” mean in the time of Covid-19? Amid the debates about how we might return to work, what is being forgotten is that work is a crucial part of what the 20th-century political philosopher Hannah Arendt called the human condition. The government’s Covid-19 recovery strategy, published on 11 May, states that people will be “eased back into work” as into a dentist chair: carefully, and with face masks.

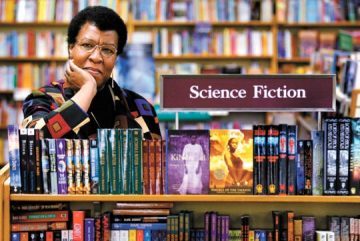

According to the government, we are now supposed to be getting back to work. But what does “work” mean in the time of Covid-19? Amid the debates about how we might return to work, what is being forgotten is that work is a crucial part of what the 20th-century political philosopher Hannah Arendt called the human condition. The government’s Covid-19 recovery strategy, published on 11 May, states that people will be “eased back into work” as into a dentist chair: carefully, and with face masks. A revolutionary voice in her lifetime, Butler has only become more popular and influential since her death 14 years ago, at age 58. Her novels, including “Dawn,” “Kindred” and “Parable of the Sower,” sell more than 100,000 copies each year, according to her former literary and the manager of her estate, Merrillee Heifetz. Toshi Reagon has adapted “Parable of the Sower” into an opera, and Viola Davis and Ava DuVernay are among those working on streaming series based on her work. Grand Central Publishing is reissuing many of her novels this year and the Library of America welcomes her to the canon in 2021 with a volume of her fiction.

A revolutionary voice in her lifetime, Butler has only become more popular and influential since her death 14 years ago, at age 58. Her novels, including “Dawn,” “Kindred” and “Parable of the Sower,” sell more than 100,000 copies each year, according to her former literary and the manager of her estate, Merrillee Heifetz. Toshi Reagon has adapted “Parable of the Sower” into an opera, and Viola Davis and Ava DuVernay are among those working on streaming series based on her work. Grand Central Publishing is reissuing many of her novels this year and the Library of America welcomes her to the canon in 2021 with a volume of her fiction. Edward Luce in the FT:

Edward Luce in the FT: Our most ecstatic modern practitioner might be Wayne Koestenbaum, the polymathic poet and essayist. (He’s also a painter and pianist.) His work — rueful, cerebral, gloriously smutty — includes trance poetry and automatic writing. He has published sections of his notebooks, trippy discursions into his obsessions with opera (“The Queen’s Throat”) and Jacqueline Onassis (“Jackie Under My Skin”), a novel about a hotel where the guest services include having your certainties shredded (“Hotel Theory”). Whatever his subject — favorites include porn, punctuation and the poetry of Frank O’Hara — the goal is always to jigger logic and language free of its moorings. “The writer’s obligation,” he states in his new essay collection, “Figure It Out,” “is to play with words and to keep playing with them, not to deracinate or deplete them, but to use them as vehicles for discovering history, recovering wounds, reciting damage and awakening conscience.”

Our most ecstatic modern practitioner might be Wayne Koestenbaum, the polymathic poet and essayist. (He’s also a painter and pianist.) His work — rueful, cerebral, gloriously smutty — includes trance poetry and automatic writing. He has published sections of his notebooks, trippy discursions into his obsessions with opera (“The Queen’s Throat”) and Jacqueline Onassis (“Jackie Under My Skin”), a novel about a hotel where the guest services include having your certainties shredded (“Hotel Theory”). Whatever his subject — favorites include porn, punctuation and the poetry of Frank O’Hara — the goal is always to jigger logic and language free of its moorings. “The writer’s obligation,” he states in his new essay collection, “Figure It Out,” “is to play with words and to keep playing with them, not to deracinate or deplete them, but to use them as vehicles for discovering history, recovering wounds, reciting damage and awakening conscience.” Kevin Hartnett in Quanta Magazine:

Kevin Hartnett in Quanta Magazine: Thomas Meaney in The New Yorker:

Thomas Meaney in The New Yorker: Rudrangshu Mukherjee reviews Partha K. Chatterjee’s I Am The People, in The India Forum:

Rudrangshu Mukherjee reviews Partha K. Chatterjee’s I Am The People, in The India Forum: