Chris Murphy in BJMP:

As a philosopher turned GP myself, David Hume has long been my favourite philosopher. He lived in 18th-century Scotland, with renowned Scottish physician William Cullen as his own doctor and friend. Hume attended university at age 12, early even in those days, pushing himself so far that he ended up developing the ‘Disease of the Learned’ — a malady that seems to have been a sort of depression or nervous breakdown. Philosophers can suffer from burnout too.

As a philosopher turned GP myself, David Hume has long been my favourite philosopher. He lived in 18th-century Scotland, with renowned Scottish physician William Cullen as his own doctor and friend. Hume attended university at age 12, early even in those days, pushing himself so far that he ended up developing the ‘Disease of the Learned’ — a malady that seems to have been a sort of depression or nervous breakdown. Philosophers can suffer from burnout too.

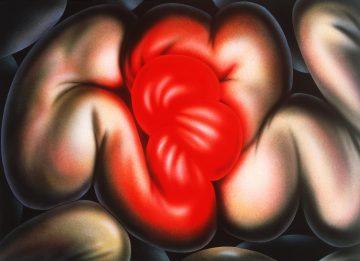

In philosophical circles, Hume is considered to be ‘one of the most important philosophers to write in English’1 but his isn’t the name that springs to mind if the man on the street is asked to name a famous philosopher. In fact, there’s much to recommend Hume as the most ‘GP’ figure of the Enlightenment. In An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding he sets out to apply the scientific method to the study of human nature. I can’t think of a more succinct way to describe the aims of modern general practice. A morning surgery can provide several patients with not much in the way of textbook pathology, but human nature is always on full display. If Hume himself was sitting in on my consultations, I imagine him suggesting that, because reason is ‘impotent’, I must ‘excite the moral passions’ of my patients. If smokers really wish to change their behaviour, Hume would think that it is not enough to print ‘SMOKING KILLS’ on the packet — you must also include a disgusting picture of a diseased lung. And he might have a point.

Hume teaches humility. A recent thoughtful editorial about medically unexplained symptoms2 drew a variety of responses. It is clear that, for some doctors, the idea that certain things might be ‘unexplained’ or even ‘unexplainable’ is anathema. Their message is clear: we must simply try harder.3

But Hume spilt a lot of ink concerning the idea of cause and effect, and indeed expressed ‘sceptical doubts concerning the operations of the understanding’.4 He thought many of the beliefs we form seem to be the product of ‘some instinct or mechanical tendency’ rather than any truly rational process.

More here.

Kuhn, who has written before about white working-class Americans, builds his book on long-ago police records and witness statements to recreate in painful detail a May day of rage, menace and blood. Antiwar demonstrators had massed at Federal Hall and other Lower Manhattan locations, only to be set upon brutally, and cravenly, by hundreds of steamfitters, ironworkers, plumbers and other laborers from nearby construction sites like the nascent World Trade Center. Many of those men had served in past wars and viscerally despised the protesters as a bunch of pampered, longhaired, draft-dodging, flag-desecrating snotnoses.

Kuhn, who has written before about white working-class Americans, builds his book on long-ago police records and witness statements to recreate in painful detail a May day of rage, menace and blood. Antiwar demonstrators had massed at Federal Hall and other Lower Manhattan locations, only to be set upon brutally, and cravenly, by hundreds of steamfitters, ironworkers, plumbers and other laborers from nearby construction sites like the nascent World Trade Center. Many of those men had served in past wars and viscerally despised the protesters as a bunch of pampered, longhaired, draft-dodging, flag-desecrating snotnoses. Megha Majumdar’s polyphonic debut novel,

Megha Majumdar’s polyphonic debut novel,  If you could shrink small enough to descend the genetic helix of any animal, plant, fungus, bacterium or virus on Earth as though it were a spiral staircase, you would always find yourself turning right — never left. It’s a universal trait in want of an explanation.

If you could shrink small enough to descend the genetic helix of any animal, plant, fungus, bacterium or virus on Earth as though it were a spiral staircase, you would always find yourself turning right — never left. It’s a universal trait in want of an explanation. Annexation looks like the executioner of the two-state solution. Israel has changed the facts on the ground, with the rapid growth of settlements rendering that goal less and less viable. But the declaration of sovereignty over parts of the occupied territories, in putting a formal seal on physical realities, will be a new and terrible moment, and above all a fresh injustice to Palestinians.

Annexation looks like the executioner of the two-state solution. Israel has changed the facts on the ground, with the rapid growth of settlements rendering that goal less and less viable. But the declaration of sovereignty over parts of the occupied territories, in putting a formal seal on physical realities, will be a new and terrible moment, and above all a fresh injustice to Palestinians. T

T

The second-worst thing about cancer chairs is that they are attached to televisions. Someone somewhere is always at war with silence. It’s impossible to read, so I answer email, or watch some cop drama on my computer, or, if it seems unavoidable, explore the lives of my nurses. A trip to Cozumel with old girlfriends, a costume party with political overtones, an advanced degree on the internet: they’re all the same, these lives, which is to say that the nurses tell me nothing, perhaps because amid the din and pain it’s impossible to say anything of substance, or perhaps because they know that nothing is precisely what we both expect. It’s the very currency of the place. Perhaps they are being excruciatingly candid.

The second-worst thing about cancer chairs is that they are attached to televisions. Someone somewhere is always at war with silence. It’s impossible to read, so I answer email, or watch some cop drama on my computer, or, if it seems unavoidable, explore the lives of my nurses. A trip to Cozumel with old girlfriends, a costume party with political overtones, an advanced degree on the internet: they’re all the same, these lives, which is to say that the nurses tell me nothing, perhaps because amid the din and pain it’s impossible to say anything of substance, or perhaps because they know that nothing is precisely what we both expect. It’s the very currency of the place. Perhaps they are being excruciatingly candid. In 2005, Barry Marshall, an Australian gastroenterologist and researcher, shared the Nobel Prize in Medicine for the discovery that peptic ulcers are caused not by stress, as was commonly thought, but by a bacterium called

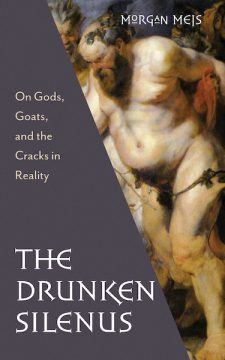

In 2005, Barry Marshall, an Australian gastroenterologist and researcher, shared the Nobel Prize in Medicine for the discovery that peptic ulcers are caused not by stress, as was commonly thought, but by a bacterium called  In his new book, The Drunken Silenus,

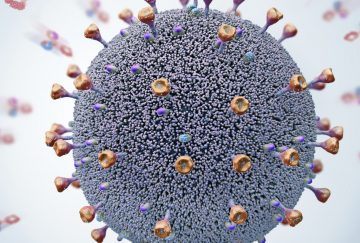

In his new book, The Drunken Silenus,  A pair of studies published this week is shedding light on the duration of immunity following COVID-19, showing patients lose their IgG antibodies—the virus-specific, slower-forming antibodies associated with long-term immunity—within weeks or months after recovery. With COVID-19, most people who become infected do

A pair of studies published this week is shedding light on the duration of immunity following COVID-19, showing patients lose their IgG antibodies—the virus-specific, slower-forming antibodies associated with long-term immunity—within weeks or months after recovery. With COVID-19, most people who become infected do  On Saturday, the

On Saturday, the In one of the twentieth century’s most memorable scenes from literature, a man is standing on a beach, pulling on a long rope that stretches out to sea. The rope is covered in thick seaweed. He yanks and tugs, and out of the foaming waves comes a horse’s head. It’s black and shiny and lies there at the water’s edge, its dead eyes staring while greenish eels slither from every orifice. The eels crawl out, shiny and entrails-like, more than two dozen of them; when the man has shoved them all into a potato sack, he pries open the horse’s grinning mouth, sticks his hands into its throat, and pulls out two more eels, as thick as his own arms.

In one of the twentieth century’s most memorable scenes from literature, a man is standing on a beach, pulling on a long rope that stretches out to sea. The rope is covered in thick seaweed. He yanks and tugs, and out of the foaming waves comes a horse’s head. It’s black and shiny and lies there at the water’s edge, its dead eyes staring while greenish eels slither from every orifice. The eels crawl out, shiny and entrails-like, more than two dozen of them; when the man has shoved them all into a potato sack, he pries open the horse’s grinning mouth, sticks his hands into its throat, and pulls out two more eels, as thick as his own arms. Until I read Howard Means’s Splash! and Bonnie Tsui’s Why We Swim, my main encounter with the history of the sport had been a Victorian-inspired swimming gala organised by members of my local team at north London’s Parliament Hill Lido. We competed in novelty races that predated the streamlining of swimming into a competitive sport, swimming upright holding umbrellas in one race, wearing blindfolds in another. We jumped into the pool in vintage dresses to see what it was like to swim hampered by heavy fabrics.

Until I read Howard Means’s Splash! and Bonnie Tsui’s Why We Swim, my main encounter with the history of the sport had been a Victorian-inspired swimming gala organised by members of my local team at north London’s Parliament Hill Lido. We competed in novelty races that predated the streamlining of swimming into a competitive sport, swimming upright holding umbrellas in one race, wearing blindfolds in another. We jumped into the pool in vintage dresses to see what it was like to swim hampered by heavy fabrics.