From Stanford Medicine:

Imagine: You pop a pill into your mouth and swallow it. It dissolves, releasing tiny particles that are absorbed and cause only cancerous cells to secrete a specific protein into your bloodstream. Two days from now, a finger-prick blood sample will expose whether you’ve got cancer and even give a rough idea of its extent. That’s a highly futuristic concept. But its realization may be only years, not decades, away. Stanford University School of Medicine investigators administered a customized genetic construct consisting of tiny rings of DNA, called DNA minicircles, to mice. The scientists then showed that mice with tumors produced a substance that tumor-free mice didn’t make. The substance was easily detected 48 hours later by a simple blood test. The technique has the potential to apply to a broad range of cancers, so someday clinicians might be able not only to detect tumors, monitor the effectiveness of cancer therapies and guide the developments of anti-tumor drugs, but — importantly — to screen symptom-free populations for nascent tumors that might have otherwise gone undetected until they became larger and much tougher to treat.

Imagine: You pop a pill into your mouth and swallow it. It dissolves, releasing tiny particles that are absorbed and cause only cancerous cells to secrete a specific protein into your bloodstream. Two days from now, a finger-prick blood sample will expose whether you’ve got cancer and even give a rough idea of its extent. That’s a highly futuristic concept. But its realization may be only years, not decades, away. Stanford University School of Medicine investigators administered a customized genetic construct consisting of tiny rings of DNA, called DNA minicircles, to mice. The scientists then showed that mice with tumors produced a substance that tumor-free mice didn’t make. The substance was easily detected 48 hours later by a simple blood test. The technique has the potential to apply to a broad range of cancers, so someday clinicians might be able not only to detect tumors, monitor the effectiveness of cancer therapies and guide the developments of anti-tumor drugs, but — importantly — to screen symptom-free populations for nascent tumors that might have otherwise gone undetected until they became larger and much tougher to treat.

The hunt for cancer biomarkers — substances whose presence in an individual’s blood or urine flags a probable tumor — is nothing new, said the study’s senior author, Sanjiv “Sam” Gambhir, professor and chair of radiology and director of the Canary Center at Stanford for Cancer Early Detection. High blood levels of prostate-specific antigen, for example, can signify prostate cancer, and there are also biomarkers that sometimes signal ovarian and colorectal cancer, he said. But while various tumor types naturally secrete characteristic substances into the blood, the secreted substance is typically specific to the tumor type, with each requiring its own separate test. Complicating matters, these substances are also quite often made in healthy tissues, so a positive test result doesn’t absolutely mean a person actually has cancer. Or a tumor — especially a small one — simply may not secrete enough of the trademark substance to be detectable.

Gambhir’s team appears to have found a way to force any of numerous tumor types to produce a biomarker whose presence in the blood of mice unambiguously signifies cancer, because none of the rodents’ tissues — cancerous or otherwise — would normally be making it. This biomarker is a protein called secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase. SEAP is naturally produced in human embryos as they form and develop, but it’s not present in adults.

More here.

Morgan Meis: Reading your second volume, I got a feeling that sometimes you struggled – as I think everyone has struggled – with where to place Calder in art history. Do you feel you reached a conclusion on that?

Morgan Meis: Reading your second volume, I got a feeling that sometimes you struggled – as I think everyone has struggled – with where to place Calder in art history. Do you feel you reached a conclusion on that? By now they are used to sharing their knowledge with journalists, but they’re less accustomed to talking about themselves. Many of them told me that they feel duty-bound and grateful to be helping their country at a time when so many others are ill or unemployed. But they’re also very tired, and dispirited by America’s continued inability to control a virus that many other nations have brought to heel.

By now they are used to sharing their knowledge with journalists, but they’re less accustomed to talking about themselves. Many of them told me that they feel duty-bound and grateful to be helping their country at a time when so many others are ill or unemployed. But they’re also very tired, and dispirited by America’s continued inability to control a virus that many other nations have brought to heel.  They had been public servants their whole careers. But when Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 election, two departing Obama officials were anxious for work. Trump’s win had caught them by surprise.

They had been public servants their whole careers. But when Hillary Clinton lost the 2016 election, two departing Obama officials were anxious for work. Trump’s win had caught them by surprise. To be sure, enlightened progressives were committed to science, positivism, and liberal democratic values—all of which the reactionaries rejected in favor of hierarchy and a highly traditionalist, and exclusively Catholic nationalism. It would seem to be a clear-cut struggle between the modernists and the antimodernists, but not as as Péguy saw it. He found the progressive faith in a scientifically driven and ever-improving future no more immanentizing, and no more modernist in its deepest aspirations, than the reactionaries’ vision. “These wrathful particularists,” Maguire explains, “often intimate a loyalty to older notions of transcendence—including religious faith and its avowal of abiding truths—but they conceive of that which transcends time only as an arrested immanence. They often present an amalgamated past as a unity…which now must be reinserted mechanically into the present, without creativity or surprise.” More ironically, some of the faux antimodernists (including the right-wing Action Française founder Charles Maurras, an admirer of the positivist Auguste Comte) also believed that “‘science’ would “confirm their particularism and prejudices.” Péguy’s critical stance toward both broad coalitions made him neither a modernist nor an antimodernist, Maguire argues, but something quite distinctive and instructive: an amodernist.

To be sure, enlightened progressives were committed to science, positivism, and liberal democratic values—all of which the reactionaries rejected in favor of hierarchy and a highly traditionalist, and exclusively Catholic nationalism. It would seem to be a clear-cut struggle between the modernists and the antimodernists, but not as as Péguy saw it. He found the progressive faith in a scientifically driven and ever-improving future no more immanentizing, and no more modernist in its deepest aspirations, than the reactionaries’ vision. “These wrathful particularists,” Maguire explains, “often intimate a loyalty to older notions of transcendence—including religious faith and its avowal of abiding truths—but they conceive of that which transcends time only as an arrested immanence. They often present an amalgamated past as a unity…which now must be reinserted mechanically into the present, without creativity or surprise.” More ironically, some of the faux antimodernists (including the right-wing Action Française founder Charles Maurras, an admirer of the positivist Auguste Comte) also believed that “‘science’ would “confirm their particularism and prejudices.” Péguy’s critical stance toward both broad coalitions made him neither a modernist nor an antimodernist, Maguire argues, but something quite distinctive and instructive: an amodernist. “I see no reason not to consider the Brontë cult a religion,” writes Judith Shulevitz. She calls the thousands of books inspired by the Brontës midrash, “the spinning of gloriously weird backstories or fairy tales prompted by gaps or contradictions in the narrative.”

“I see no reason not to consider the Brontë cult a religion,” writes Judith Shulevitz. She calls the thousands of books inspired by the Brontës midrash, “the spinning of gloriously weird backstories or fairy tales prompted by gaps or contradictions in the narrative.” When Howard Wolinsky was diagnosed with

When Howard Wolinsky was diagnosed with  In her 2019 book, “

In her 2019 book, “ A man finds himself in Antwerp with nothing to do. Then he remembers, among other things, that this is the town where the painter Peter Paul Rubens made his home. At first, this annoys him, because he has no interest whatsoever in the painter. But then he thinks, why not write a book about Rubens.

A man finds himself in Antwerp with nothing to do. Then he remembers, among other things, that this is the town where the painter Peter Paul Rubens made his home. At first, this annoys him, because he has no interest whatsoever in the painter. But then he thinks, why not write a book about Rubens. Creativity is one of those things that we all admire but struggle to define or make concrete. Music provides a useful laboratory in which to examine what creativity is all about — how do people become creative, what is happening in their brains during the creative process, and what kinds of creativity does the audience actually enjoy? David Rosen and Scott Miles are both neuroscientists and musicians who have been investigating this question from the perspective of both listeners and performers. They have been performing neuroscientific experiments to understand how the brain becomes creative, and founded Secret Chord Laboratories to develop software that will predict what kinds of music people will like.

Creativity is one of those things that we all admire but struggle to define or make concrete. Music provides a useful laboratory in which to examine what creativity is all about — how do people become creative, what is happening in their brains during the creative process, and what kinds of creativity does the audience actually enjoy? David Rosen and Scott Miles are both neuroscientists and musicians who have been investigating this question from the perspective of both listeners and performers. They have been performing neuroscientific experiments to understand how the brain becomes creative, and founded Secret Chord Laboratories to develop software that will predict what kinds of music people will like.

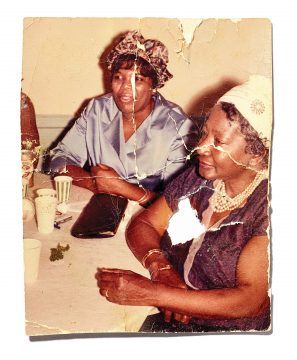

As a boy in Brownsville and in Bed-Stuy, I was tormented by the question of protection, because, of course, I, too, wanted to be protected. Like any number of black boys in those neighborhoods, I grew up in a matrilineal society, where I had been taught the power—the necessity—of silence. But how could you not cry out when you couldn’t save your mother because you couldn’t defend yourself? Although I had this in common with other guys, something separated me from them when it came to joining those demonstrations, to leaping in the air when black bodies were threatened. My distance had to do with my queerness. The guys who took the chance to protect their families and themselves were the same guys who called me “faggot.”

As a boy in Brownsville and in Bed-Stuy, I was tormented by the question of protection, because, of course, I, too, wanted to be protected. Like any number of black boys in those neighborhoods, I grew up in a matrilineal society, where I had been taught the power—the necessity—of silence. But how could you not cry out when you couldn’t save your mother because you couldn’t defend yourself? Although I had this in common with other guys, something separated me from them when it came to joining those demonstrations, to leaping in the air when black bodies were threatened. My distance had to do with my queerness. The guys who took the chance to protect their families and themselves were the same guys who called me “faggot.” What is to be done with hope? Ali Smith is a great artist of possibility. Think of the role chance plays in her work, from The Accidental to How to be Both’s thrillingly shuffled structure that meant you had a fifty-fifty chance of getting the contemporary narrative first or the historical one. But these are bleak times – from Smith’s perspective, anyway, which I should state here is broadly my own too.

What is to be done with hope? Ali Smith is a great artist of possibility. Think of the role chance plays in her work, from The Accidental to How to be Both’s thrillingly shuffled structure that meant you had a fifty-fifty chance of getting the contemporary narrative first or the historical one. But these are bleak times – from Smith’s perspective, anyway, which I should state here is broadly my own too. Many historians have noted the intimate connection between the theory of natural selection and the ascendant political and economic views of the society in which Darwin was a well-placed member. The Victorian elite were committed to the idea that the unfettered competition of Adam Smith and David Ricardo’s free market would drive economic and social advancement. In Darwin’s theory, they found nature’s own reflection of the social system they favored. As J.M. Keynes put it, “The principle of the survival of the fittest could be regarded as a vast generalization of the Ricardian economics.”

Many historians have noted the intimate connection between the theory of natural selection and the ascendant political and economic views of the society in which Darwin was a well-placed member. The Victorian elite were committed to the idea that the unfettered competition of Adam Smith and David Ricardo’s free market would drive economic and social advancement. In Darwin’s theory, they found nature’s own reflection of the social system they favored. As J.M. Keynes put it, “The principle of the survival of the fittest could be regarded as a vast generalization of the Ricardian economics.”