—after Neil deGrasse Tyson, black astrophysicist & director of the Hayden Planetarium, born in 1958, New York City. In his youth, deGrasse Tyson was confronted by police on more than one occasion when he was on his way to study stars.

The Black Maria

The Skyview apartments

…………. circa 1973, a boy is

kneeling on the rooftop, a boy who

…………. (it is important

to mention here his skin

…………. is brown) prepares his telescope,

the weights & rods,

…………. to better see the moon. His neighbor

(it is important to mention here

…………. that she is white) calls the police

because she suspects the brown boy

…………. of something, she does not know

what at first, then turns,

…………. with her white looking,

his telescope into a gun,

…………. his duffel into a bag of objects

thieved from the neighbors’ houses

…………. (maybe even hers) & the police

(it is important to mention

…………. that statistically they

are also white) arrive to find

…………. the boy who has been turned, by now,

into “the suspect,” on the roof

…………. with a long, black lens, which is,

in the neighbor’s mind, a weapon &

…………. depending on who you are, reading this,

you know that the boy is in grave danger,

…………. & you might have known

somewhere quiet in your gut,

…………. you might have worried for him

in the white space between lines 5 & 6,

…………. or maybe even earlier, & you might be holding

your breath for him right now

…………. because you know this story,

it’s a true story, though,

…………. miraculously, in this version

of the story anyway,

…………. the boy on the roof of the Skyview lives

Read more »

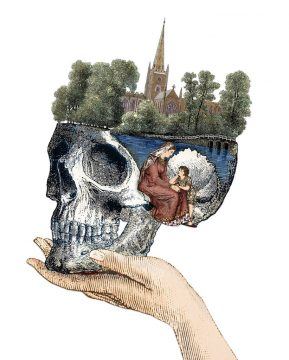

“Hamnet” is an exploration of marriage and grief written into the silent opacities of a life that is at once extremely famous and profoundly obscure. Countless scholars have combed through Elizabethan England’s parish and court records looking for traces of William Shakespeare. But what we know for sure, if set down unvarnished by learned and often fascinating speculation, would barely make a slender monograph. As William Styron once wrote, the historical novelist works best when fed on short rations. The rations at Maggie O’Farrell’s disposal are scant but tasty, just the kind of morsels to nourish an empathetic imagination. We know, for instance, that at the age of 18, Shakespeare married a woman named Anne or Agnes Hathaway, who was 26 and three months pregnant. (That condition wasn’t unusual for the time: Studies of marriage and baptism records reveal that as many as one-third of brides went to the altar pregnant.) Hathaway was the orphaned daughter of a farmer near Stratford-upon-Avon who had bequeathed her a dowry. This status gave her more latitude than many women of her time, who relied on paternal permission in choosing a mate.

“Hamnet” is an exploration of marriage and grief written into the silent opacities of a life that is at once extremely famous and profoundly obscure. Countless scholars have combed through Elizabethan England’s parish and court records looking for traces of William Shakespeare. But what we know for sure, if set down unvarnished by learned and often fascinating speculation, would barely make a slender monograph. As William Styron once wrote, the historical novelist works best when fed on short rations. The rations at Maggie O’Farrell’s disposal are scant but tasty, just the kind of morsels to nourish an empathetic imagination. We know, for instance, that at the age of 18, Shakespeare married a woman named Anne or Agnes Hathaway, who was 26 and three months pregnant. (That condition wasn’t unusual for the time: Studies of marriage and baptism records reveal that as many as one-third of brides went to the altar pregnant.) Hathaway was the orphaned daughter of a farmer near Stratford-upon-Avon who had bequeathed her a dowry. This status gave her more latitude than many women of her time, who relied on paternal permission in choosing a mate. One night in August 2005, just after I’d moved to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, for a job as a theology professor, I needed beer. To get to the distributor, I drove over a concrete bridge, its four pylons etched with words like “Perseverance” and “Industry” and topped by monumental eagles. Once there, I wandered through the pallets of warm cases trying to find a thirty-pack of PBR until the thin, gruff man behind the counter asked what I was looking for. I told him, he pointed to the right pallet, and I met him at the register.

One night in August 2005, just after I’d moved to Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, for a job as a theology professor, I needed beer. To get to the distributor, I drove over a concrete bridge, its four pylons etched with words like “Perseverance” and “Industry” and topped by monumental eagles. Once there, I wandered through the pallets of warm cases trying to find a thirty-pack of PBR until the thin, gruff man behind the counter asked what I was looking for. I told him, he pointed to the right pallet, and I met him at the register. Seven years ago

Seven years ago The thesis of Bjorn Lomborg’s “False Alarm” is simple and simplistic: Activists have been sounding a false alarm about the dangers of climate change. If we listen to them, Lomborg says, we will waste trillions of dollars, achieve little and the poor will suffer the most. Science has provided a way to carefully balance costs and benefits, if we would only listen to its clarion call. And, of course, the villain in this “false alarm,” the boogeyman for all of society’s ills, is the hyperventilating media. Lomborg doesn’t use the term “fake news,” but it’s there if you read between the lines.

The thesis of Bjorn Lomborg’s “False Alarm” is simple and simplistic: Activists have been sounding a false alarm about the dangers of climate change. If we listen to them, Lomborg says, we will waste trillions of dollars, achieve little and the poor will suffer the most. Science has provided a way to carefully balance costs and benefits, if we would only listen to its clarion call. And, of course, the villain in this “false alarm,” the boogeyman for all of society’s ills, is the hyperventilating media. Lomborg doesn’t use the term “fake news,” but it’s there if you read between the lines. T

T This isn’t a style of the Church, Italy, a patron, or a doctrine. It’s a personal style, the work of a self-taught 40-something gay man who devised ways to dye one’s hair blond as well as build bridges. Art history has been going through regular stylistic shifts ever since. This is what a social revolution looks like.

This isn’t a style of the Church, Italy, a patron, or a doctrine. It’s a personal style, the work of a self-taught 40-something gay man who devised ways to dye one’s hair blond as well as build bridges. Art history has been going through regular stylistic shifts ever since. This is what a social revolution looks like. In the summer of 1977, on a field trip in northern Patagonia, the American archaeologist Tom Dillehay made a stunning discovery. Digging by a creek in a nondescript scrubland called Monte Verde, in southern Chile, he came upon the remains of an ancient camp. A full excavation uncovered the trace wooden foundations of no fewer than 12 huts, plus one larger structure designed for tool manufacture and perhaps as an infirmary. In the large hut, Dillehay found gnawed bones, spear points, grinding tools and, hauntingly, a human footprint in the sand. The ancestral Patagonians—inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego and the Magellan Straits—had erected their domestic quarters using branches from the beech trees of a long-gone temperate forest, then covered them with the hides of vanished ice age species, including mastodons, saber-toothed cats, and giant sloths.

In the summer of 1977, on a field trip in northern Patagonia, the American archaeologist Tom Dillehay made a stunning discovery. Digging by a creek in a nondescript scrubland called Monte Verde, in southern Chile, he came upon the remains of an ancient camp. A full excavation uncovered the trace wooden foundations of no fewer than 12 huts, plus one larger structure designed for tool manufacture and perhaps as an infirmary. In the large hut, Dillehay found gnawed bones, spear points, grinding tools and, hauntingly, a human footprint in the sand. The ancestral Patagonians—inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego and the Magellan Straits—had erected their domestic quarters using branches from the beech trees of a long-gone temperate forest, then covered them with the hides of vanished ice age species, including mastodons, saber-toothed cats, and giant sloths. A breathalyzer designed to detect multiple cancers early is being tested in the UK. Several illnesses

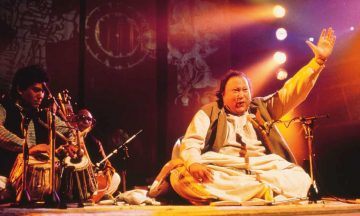

A breathalyzer designed to detect multiple cancers early is being tested in the UK. Several illnesses Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan

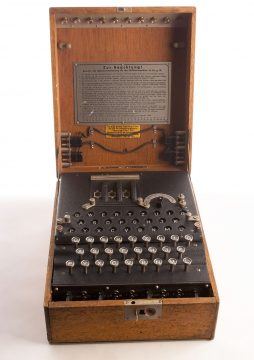

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan In 1931, the Austrian logician Kurt Gödel pulled off arguably one of the most stunning intellectual achievements in history.

In 1931, the Austrian logician Kurt Gödel pulled off arguably one of the most stunning intellectual achievements in history. There are two boxes on a table, one red and one green. One contains a treasure. The red box is labelled “exactly one of the labels is true”. The green box is labelled “the treasure is in this box.”

There are two boxes on a table, one red and one green. One contains a treasure. The red box is labelled “exactly one of the labels is true”. The green box is labelled “the treasure is in this box.” WHAT IS A WOMAN’S MARGINAL UTILITY?

WHAT IS A WOMAN’S MARGINAL UTILITY? By the halfway point in my journey through Lonesome Dove two things started happening. As I began communicating my Keats-on-Chapman’s-Homer “discovery” to friends, it became clear that the book inspired something more akin to faith than admiration or love. People hadn’t just read the book; they had converted or pledged allegiance to it. When a friend came to dinner and saw my copy on the table she explained that she had been given the middle name MacRae, in honour of Gus. I fell prey to a kind of fanaticism myself, emailing an unsuspecting Zadie Smith to ask why anyone would bother with even a page of Saul Bellow when they could be immersed in Lonesome Dove. When she wrote back that she couldn’t bear Bellow or westerns I was tempted to respond, insanely, that it wasn’t a western. And yet – to deploy a favourite hesitation of Steiner’s – perhaps an underlying sanity or logic was at work.

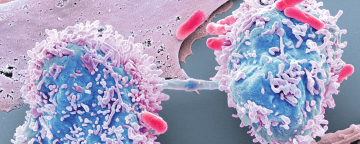

By the halfway point in my journey through Lonesome Dove two things started happening. As I began communicating my Keats-on-Chapman’s-Homer “discovery” to friends, it became clear that the book inspired something more akin to faith than admiration or love. People hadn’t just read the book; they had converted or pledged allegiance to it. When a friend came to dinner and saw my copy on the table she explained that she had been given the middle name MacRae, in honour of Gus. I fell prey to a kind of fanaticism myself, emailing an unsuspecting Zadie Smith to ask why anyone would bother with even a page of Saul Bellow when they could be immersed in Lonesome Dove. When she wrote back that she couldn’t bear Bellow or westerns I was tempted to respond, insanely, that it wasn’t a western. And yet – to deploy a favourite hesitation of Steiner’s – perhaps an underlying sanity or logic was at work. In the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage, a team of scientists is shrunk to fit into a tiny submarine so that they can navigate their colleague’s vasculature and rid him of a deadly blood clot in his brain. This classic film is one of many such imaginative biological journeys that have made it to the big screen over the past several decades. At the same time, scientists have been working to make a similar vision a reality: tiny robots roaming the human body to detect and treat disease.

In the 1966 movie Fantastic Voyage, a team of scientists is shrunk to fit into a tiny submarine so that they can navigate their colleague’s vasculature and rid him of a deadly blood clot in his brain. This classic film is one of many such imaginative biological journeys that have made it to the big screen over the past several decades. At the same time, scientists have been working to make a similar vision a reality: tiny robots roaming the human body to detect and treat disease.