Carlos Clarens and Edgardo Cozarinsky interview Jazques Rivette at Sight and Sound:

JACQUES RIVETTE: When I began making films my point of view was that of a cinephile, so my ideas about what I wanted to do were abstract. Then, after the experience of my first two films, I realised I had taken the wrong direction as regards methods of shooting. The cinema of mise en scène, where everything is carefully preplanned and where you try to ensure that what is seen on the screen corresponds as closely as possible to your original plan, was not a method in which I felt at ease or worked well. What bothered me from the outset, after I had finally managed to finish Paris Nous Appartient with all its tribulations, was what the characters said, the words they used. I had written the dialogue beforehand with my co-writer Jean Gruault (though I was 90 per cent responsible) and then it was reworked and pruned during shooting, as the film otherwise would have run four-and-a-half hours. The actors sometimes changed a word here and there, as always happens in films, but basically the dialogue was what I had written – and I found it a source of intense embarrassment. So much so that when I began work on La Religieuse, which was a project that took quite a while to get off the ground, I determined this time to use what was basically a pre-existing text.

JACQUES RIVETTE: When I began making films my point of view was that of a cinephile, so my ideas about what I wanted to do were abstract. Then, after the experience of my first two films, I realised I had taken the wrong direction as regards methods of shooting. The cinema of mise en scène, where everything is carefully preplanned and where you try to ensure that what is seen on the screen corresponds as closely as possible to your original plan, was not a method in which I felt at ease or worked well. What bothered me from the outset, after I had finally managed to finish Paris Nous Appartient with all its tribulations, was what the characters said, the words they used. I had written the dialogue beforehand with my co-writer Jean Gruault (though I was 90 per cent responsible) and then it was reworked and pruned during shooting, as the film otherwise would have run four-and-a-half hours. The actors sometimes changed a word here and there, as always happens in films, but basically the dialogue was what I had written – and I found it a source of intense embarrassment. So much so that when I began work on La Religieuse, which was a project that took quite a while to get off the ground, I determined this time to use what was basically a pre-existing text.

more here.

“[Jacques Rivette’s] whole movie, like a dream, is set between quotation marks,” Gilbert Adair suggested in Film Comment in 1974. “Like a dream, it is an anagram of reality.” The simplest way to explain the film – if there is a simple way to explain it – is that at some point Celine enters a remote mansion on the outskirts of the city, loses track of time, and ends up thrown back into daylight after an unspecified number of hours. She is dazed, and has no memory of what occurred inside the house, but feels compelled to keep returning.

“[Jacques Rivette’s] whole movie, like a dream, is set between quotation marks,” Gilbert Adair suggested in Film Comment in 1974. “Like a dream, it is an anagram of reality.” The simplest way to explain the film – if there is a simple way to explain it – is that at some point Celine enters a remote mansion on the outskirts of the city, loses track of time, and ends up thrown back into daylight after an unspecified number of hours. She is dazed, and has no memory of what occurred inside the house, but feels compelled to keep returning. The larger question lurking behind the debate over “cancel culture” is the one about liberalism—to wit, what is liberalism, anyway? And why should we care about it? I signed the Harper’s “

The larger question lurking behind the debate over “cancel culture” is the one about liberalism—to wit, what is liberalism, anyway? And why should we care about it? I signed the Harper’s “ A young Ernest Hemingway, badly injured by an exploding shell on a World War I battlefield, wrote in a letter home that “dying is a very simple thing. I’ve looked at death, and really I know. If I should have died it would have been very easy for me. Quite the easiest thing I ever did.” Years later Hemingway adapted his own experience—that of the soul leaving the body, taking flight and then returning—for his famous short story “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” about an African safari gone disastrously wrong. The protagonist, stricken by gangrene, knows he is dying. Suddenly, his pain vanishes, and Compie, a bush pilot, arrives to rescue him. The two take off and fly together through a storm with rain so thick “it seemed like flying through a waterfall” until the plane emerges into the light: before them, “unbelievably white in the sun, was the square top of Kilimanjaro. And then he knew that there was where he was going.” The description embraces elements of a classic near-death experience: the darkness, the cessation of pain, the emerging into the light and then a feeling of peacefulness.

A young Ernest Hemingway, badly injured by an exploding shell on a World War I battlefield, wrote in a letter home that “dying is a very simple thing. I’ve looked at death, and really I know. If I should have died it would have been very easy for me. Quite the easiest thing I ever did.” Years later Hemingway adapted his own experience—that of the soul leaving the body, taking flight and then returning—for his famous short story “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” about an African safari gone disastrously wrong. The protagonist, stricken by gangrene, knows he is dying. Suddenly, his pain vanishes, and Compie, a bush pilot, arrives to rescue him. The two take off and fly together through a storm with rain so thick “it seemed like flying through a waterfall” until the plane emerges into the light: before them, “unbelievably white in the sun, was the square top of Kilimanjaro. And then he knew that there was where he was going.” The description embraces elements of a classic near-death experience: the darkness, the cessation of pain, the emerging into the light and then a feeling of peacefulness. A grimace revealing powerful yellow incisors clearly indicated we were too close. As our game drive vehicle gently reversed, the female leopard, Thandi, relaxed and settled back in the thicket with her seven-month-old cub, panting as she digested her latest kill. An impala carcass hung limply in the branches nearby. Leopards are famously elusive – but here in the private Sabi Sands Game Reserve, on the edge of Kruger National Park in South Africa, these cats are so habituated to human presence, they’re commonly seen strolling nonchalantly past vehicles of tourists, unconcerned by the frantic clicking of cameras. Though their presence in the Sabi Sands might suggest otherwise, South Africa’s leopard population faces an uncertain future. In a country where reserves and national parks are surrounded by farms, roads and developments, leopards have been forced into ever smaller areas. In some populations, as one recent paper shows,

A grimace revealing powerful yellow incisors clearly indicated we were too close. As our game drive vehicle gently reversed, the female leopard, Thandi, relaxed and settled back in the thicket with her seven-month-old cub, panting as she digested her latest kill. An impala carcass hung limply in the branches nearby. Leopards are famously elusive – but here in the private Sabi Sands Game Reserve, on the edge of Kruger National Park in South Africa, these cats are so habituated to human presence, they’re commonly seen strolling nonchalantly past vehicles of tourists, unconcerned by the frantic clicking of cameras. Though their presence in the Sabi Sands might suggest otherwise, South Africa’s leopard population faces an uncertain future. In a country where reserves and national parks are surrounded by farms, roads and developments, leopards have been forced into ever smaller areas. In some populations, as one recent paper shows,  HIV infects the body through a protein on the surface of white blood cells. A tiny percentage of people have no functional receptors for this protein, meaning they can have sex with whomever they want and never risk contracting the virus. Other people, like the poet Jameson Fitzpatrick’s uncle, have fewer working receptors, so HIV is harder for them to contract, develops more slowly, and leads to less abundant viral loads. “Roughly,” about his uncle, is the longest poem in Fitzpatrick’s new collection Pricks in the Tapestry, a book that often views queer cultural inheritance in the 21st century from the vantage of past generations.

HIV infects the body through a protein on the surface of white blood cells. A tiny percentage of people have no functional receptors for this protein, meaning they can have sex with whomever they want and never risk contracting the virus. Other people, like the poet Jameson Fitzpatrick’s uncle, have fewer working receptors, so HIV is harder for them to contract, develops more slowly, and leads to less abundant viral loads. “Roughly,” about his uncle, is the longest poem in Fitzpatrick’s new collection Pricks in the Tapestry, a book that often views queer cultural inheritance in the 21st century from the vantage of past generations.

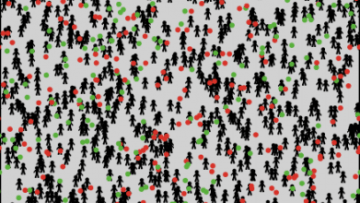

The distribution of wealth follows a well-known pattern sometimes called an 80:20 rule: 80 percent of the wealth is owned by 20 percent of the people. Indeed, a report last year concluded that just eight men had a total wealth equivalent to that of the world’s poorest 3.8 billion people.

The distribution of wealth follows a well-known pattern sometimes called an 80:20 rule: 80 percent of the wealth is owned by 20 percent of the people. Indeed, a report last year concluded that just eight men had a total wealth equivalent to that of the world’s poorest 3.8 billion people. The key consequence of seeing the humanities as a world alongside other broadly similar worlds is that the limits of their defensibility becomes apparent, and sermonizing over them becomes harder. If people stopped watching and playing sports, how much would it matter? The question is unanswerable since we can’t imagine a society continuous with ours but lacking sports, even though one such is, I suppose, possible. We do not have the means to adjudicate between that imaginary sportless society and our own actual sports-obsessed society. The same is true for the humanities. If the humanities were to disappear, new social and cultural configurations would then exist. Would this be a loss or gain? There is no way of telling, partly because we can’t picture what a society and culture that follow from ours but lack the humanities would be like at the requisite level of detail, and partly because, even if we could imagine such a society, our judgment between a society with the humanities and one without them couldn’t appeal to the standards like ours that are embedded in the humanities themselves. The humanities would be gone: that’s it.

The key consequence of seeing the humanities as a world alongside other broadly similar worlds is that the limits of their defensibility becomes apparent, and sermonizing over them becomes harder. If people stopped watching and playing sports, how much would it matter? The question is unanswerable since we can’t imagine a society continuous with ours but lacking sports, even though one such is, I suppose, possible. We do not have the means to adjudicate between that imaginary sportless society and our own actual sports-obsessed society. The same is true for the humanities. If the humanities were to disappear, new social and cultural configurations would then exist. Would this be a loss or gain? There is no way of telling, partly because we can’t picture what a society and culture that follow from ours but lack the humanities would be like at the requisite level of detail, and partly because, even if we could imagine such a society, our judgment between a society with the humanities and one without them couldn’t appeal to the standards like ours that are embedded in the humanities themselves. The humanities would be gone: that’s it. One of my favorite Earle performances is

One of my favorite Earle performances is  Here is another

Here is another  In January, Robert Williams, an African-American man, was wrongfully arrested due to an inaccurate facial recognition algorithm, a computerized approach that analyzes human faces and identifies them by comparison to database images of known people. He was handcuffed and arrested in front of his family by Detroit police without being told why, then jailed overnight after the police took mugshots, fingerprints, and a DNA sample. The next day, detectives showed Williams a surveillance video image of an African-American man standing in a store that sells watches. It immediately became clear that he was not Williams. Detailing his arrest in the

In January, Robert Williams, an African-American man, was wrongfully arrested due to an inaccurate facial recognition algorithm, a computerized approach that analyzes human faces and identifies them by comparison to database images of known people. He was handcuffed and arrested in front of his family by Detroit police without being told why, then jailed overnight after the police took mugshots, fingerprints, and a DNA sample. The next day, detectives showed Williams a surveillance video image of an African-American man standing in a store that sells watches. It immediately became clear that he was not Williams. Detailing his arrest in the

Democracy imposes a substantial moral burden on citizens. They must regard one another as political equals, even when they disagree deeply about justice. Each side is likely to see the opposition as not only wrong about the issue, but on the side of injustice. How can citizens both stand up for justice and yet embrace a political arrangement that gives injustice an equal say? Political sympathy, a disposition to recognize in our opposition an attempt to live according to their conception of value, is proposed as a way to lighten democracy’s burden.

Democracy imposes a substantial moral burden on citizens. They must regard one another as political equals, even when they disagree deeply about justice. Each side is likely to see the opposition as not only wrong about the issue, but on the side of injustice. How can citizens both stand up for justice and yet embrace a political arrangement that gives injustice an equal say? Political sympathy, a disposition to recognize in our opposition an attempt to live according to their conception of value, is proposed as a way to lighten democracy’s burden. Human civilization is only a few thousand years old (depending on how we count). So if civilization will ultimately last for millions of years, it could be considered surprising that we’ve found ourselves so early in history. Should we therefore predict that human civilization will probably disappear within a few thousand years? This “Doomsday Argument” shares a family resemblance to ideas used by many professional cosmologists to judge whether a model of the universe is natural or not. Philosopher Nick Bostrom is the world’s expert on these kinds of anthropic arguments. We talk through them, leading to the biggest doozy of them all: the idea that our perceived reality might be a computer simulation being run by enormously more powerful beings.

Human civilization is only a few thousand years old (depending on how we count). So if civilization will ultimately last for millions of years, it could be considered surprising that we’ve found ourselves so early in history. Should we therefore predict that human civilization will probably disappear within a few thousand years? This “Doomsday Argument” shares a family resemblance to ideas used by many professional cosmologists to judge whether a model of the universe is natural or not. Philosopher Nick Bostrom is the world’s expert on these kinds of anthropic arguments. We talk through them, leading to the biggest doozy of them all: the idea that our perceived reality might be a computer simulation being run by enormously more powerful beings.