Rebecca Rosen in The Atlantic:

In 1954, the Supreme Court decided that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional—but it was thousands of children who actually desegregated America’s classrooms. The task that fell to them was a brutal one. In the years following Brown v. Board of Education, vicious legal and political battles broke out; town by town, Black parents tried to send their children to white schools, and white parents—and often their children, too—tried to keep those Black kids out. They tried everything: bomb threats, beatings, protests. They physically blocked entrances to schools, vandalized lockers, threw rocks, taunted and jeered. Often, the efforts of white parents worked: Thousands upon thousands of Black kids were barred from the schools that were rightfully theirs to attend.

But eventually, in different places at different times, Black parents won. And that meant that their kids had to walk or take the bus to a school that had tried to keep them out. And then they had to walk in the door, go to their classrooms, and try to get an education—despite the hatred directed at them, despite the knowledge that their white classmates didn’t want them there, and despite being alone. They changed America, but in large part, that change was not lasting. As they grew older, many of them watched as their schools resegregated, and their work was undone. Those kids are in their 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s now. Many of them are no longer with us. But those who are have stories to tell.

More here.

Karachi is home. My bustling, chaotic city of about 20 million people on the Arabian Sea is an ethnically and religiously diverse metropolis and the commercial capital of Pakistan, generating more than half of the country’s revenue. Over the decades, Karachi has survived

Karachi is home. My bustling, chaotic city of about 20 million people on the Arabian Sea is an ethnically and religiously diverse metropolis and the commercial capital of Pakistan, generating more than half of the country’s revenue. Over the decades, Karachi has survived

It’s uncontroversial among biologists that many species have two, distinct biological sexes. They’re distinguished by the way that they package their DNA into ‘gametes’, the sex cells that merge to make a new organism. Males produce small gametes, and females produce large gametes. Male and female gametes are very different in structure, as well as in size. This is familiar from human sperm and eggs, and the same is true in worms, flies, fish, molluscs, trees, grasses and so forth.

It’s uncontroversial among biologists that many species have two, distinct biological sexes. They’re distinguished by the way that they package their DNA into ‘gametes’, the sex cells that merge to make a new organism. Males produce small gametes, and females produce large gametes. Male and female gametes are very different in structure, as well as in size. This is familiar from human sperm and eggs, and the same is true in worms, flies, fish, molluscs, trees, grasses and so forth. Over a decade ago, California put a price on carbon pollution. At first glance the policy appears to be a success: since it began in 2013, emissions have declined by more than

Over a decade ago, California put a price on carbon pollution. At first glance the policy appears to be a success: since it began in 2013, emissions have declined by more than

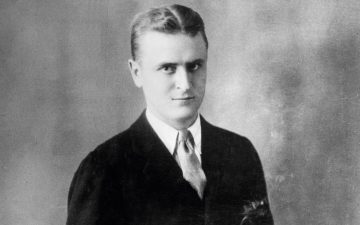

Maybe my book is rotten,” F Scott Fitzgerald told a friend, in February 1925, shortly before the publication of The Great Gatsby, “but I don’t think so”. If the first half of his sentence was perfunctory, the second half was the wildest kind of understatement. By that point, Fitzgerald knew what he had achieved. Six months earlier, he informed Maxwell Perkins, his editor at Scribner’s, that his work in progress “is about the best American novel ever written”. And Perkins’s reaction had done little to shake his sense of confidence. He called the book “a wonder”, adding: “As for sheer writing, it’s astonishing.”

Maybe my book is rotten,” F Scott Fitzgerald told a friend, in February 1925, shortly before the publication of The Great Gatsby, “but I don’t think so”. If the first half of his sentence was perfunctory, the second half was the wildest kind of understatement. By that point, Fitzgerald knew what he had achieved. Six months earlier, he informed Maxwell Perkins, his editor at Scribner’s, that his work in progress “is about the best American novel ever written”. And Perkins’s reaction had done little to shake his sense of confidence. He called the book “a wonder”, adding: “As for sheer writing, it’s astonishing.” What is America really fighting over in the upcoming election? Not any particular issue. Not even Democrats versus

What is America really fighting over in the upcoming election? Not any particular issue. Not even Democrats versus  Katrina vanden Heuvel in The Nation:

Katrina vanden Heuvel in The Nation: Sweet Dreams tactfully sidesteps whether some of the New Romantics mirrored the celebrity-for-celebrity’s sake aspirations of many of today’s vloggers and influencers. But Jones makes a convincing case that their penchant for what used to be called “gender-bending” and their sartorial obsession with self-expression as “a platform for identity” foreshadows a lot of 2020’s hot-button topics. The book is excellent on the movement’s origins both in the aspirational teenage style cult that built around Bryan Ferry in the mid-70s and the more fashion-forward occupants of the same era’s gay clubs and soul nights, who saw the clothes Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood sold in their boutique Sex not as harbingers of spittle-flecked youth revolution but as a particularly outrageous brand of couture: it’s often written out of punk’s history that, at precisely the same time the Sex Pistols’ career was getting underway, there were people in Essex dancing to disco dressed exactly like Johnny Rotten.

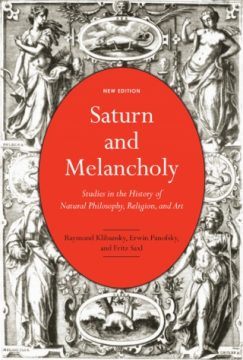

Sweet Dreams tactfully sidesteps whether some of the New Romantics mirrored the celebrity-for-celebrity’s sake aspirations of many of today’s vloggers and influencers. But Jones makes a convincing case that their penchant for what used to be called “gender-bending” and their sartorial obsession with self-expression as “a platform for identity” foreshadows a lot of 2020’s hot-button topics. The book is excellent on the movement’s origins both in the aspirational teenage style cult that built around Bryan Ferry in the mid-70s and the more fashion-forward occupants of the same era’s gay clubs and soul nights, who saw the clothes Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood sold in their boutique Sex not as harbingers of spittle-flecked youth revolution but as a particularly outrageous brand of couture: it’s often written out of punk’s history that, at precisely the same time the Sex Pistols’ career was getting underway, there were people in Essex dancing to disco dressed exactly like Johnny Rotten. If melancholia may be “[s]ometimes painful and depressing, sometimes merely mildly pensive or nostalgic,” then this new edition is, in its own right, a melancholic exercise, a wistful homage to the once-world in which the book was produced. It is also melancholic from the perspective of the contemporary reader who is able to fathom the shear catholicity of mind necessary to produce a Meisterwerk of this sort. But it is in fact that very nostalgia that is in question in the book proper, for the study lays out just how persistently the posture of scholar, artist and anchorite alike has been one of despair at the path that separates them from the great transcendence lying on the horizon, whether that goes by the name of God, the eternal intellect or the Mallarmean “Book.” And in this respect, the history of melancholy itself joins up with the story of the long, arduous path by which the book came into being.

If melancholia may be “[s]ometimes painful and depressing, sometimes merely mildly pensive or nostalgic,” then this new edition is, in its own right, a melancholic exercise, a wistful homage to the once-world in which the book was produced. It is also melancholic from the perspective of the contemporary reader who is able to fathom the shear catholicity of mind necessary to produce a Meisterwerk of this sort. But it is in fact that very nostalgia that is in question in the book proper, for the study lays out just how persistently the posture of scholar, artist and anchorite alike has been one of despair at the path that separates them from the great transcendence lying on the horizon, whether that goes by the name of God, the eternal intellect or the Mallarmean “Book.” And in this respect, the history of melancholy itself joins up with the story of the long, arduous path by which the book came into being.