Ryan Doerfler and Samuel Moyn make the case:

Progressives are taking Supreme Court reform seriously for the first time in almost a century. Owing to the rise of the political and academic left following the 2008 financial crisis and the hotly contested appointments of Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, progressives increasingly view the Supreme Court as posing a serious challenge to the successful implementation of ambitious legislation like the “Green New Deal.”

Despite this once-in-a-generation energy around the idea of court reform, the popular and academic discussion of how to reform the Supreme Court has been unduly constrained and is now at risk of closing prematurely. This is the case with regard to its mechanism and its purpose alike. On the left, historical memory has limited debate almost entirely to “court packing.” Meanwhile the center has occupied itself with how to restore the Supreme Court’s legitimacy, rescuing the institution from its regrettable slide into partisanship. And now with the Court appearing to moderate to preempt legislative reform of the institution, the concern is that progressives will drop their demands for change, satisfied with a few modest judicial concessions.

This Article aims to keep the discussion of court reform alive and, just as importantly, to significantly expand its bounds. It does so, first, by urging progressives to reject the legitimacy frame of the issue, which treats the problem with the Supreme Court as one of politicization, in favor of an openly progressive frame in which the question is how to enable democracy within our constitutional scheme.

More here.

Shuvatri Dasgupta over at the blog of the Journal of the History of Ideas:

Shuvatri Dasgupta over at the blog of the Journal of the History of Ideas: Branko Milanovic in Global Policy:

Branko Milanovic in Global Policy: A veil of solemnity descends upon the land at times like this, when elected officials or public figures get sick or die. We wish them speedy recovery, or extend sympathies, as we should. We ignore their faults and failings, as we would want our own ignored. These are the norms of politics and public life. Established norms, like behaving with dignity and self-restraint in a presidential debate, or condemning racist terrorists and murderers. For the record, we should all wish Donald and Melania Trump a full and speedy recovery. But that does not answer the fundamental question this president will leave behind when he leaves office. What norms survive a man who takes pleasure in destroying norms?

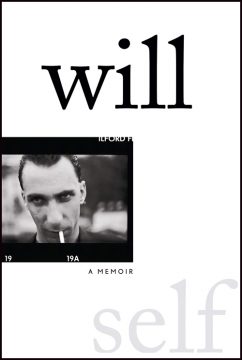

A veil of solemnity descends upon the land at times like this, when elected officials or public figures get sick or die. We wish them speedy recovery, or extend sympathies, as we should. We ignore their faults and failings, as we would want our own ignored. These are the norms of politics and public life. Established norms, like behaving with dignity and self-restraint in a presidential debate, or condemning racist terrorists and murderers. For the record, we should all wish Donald and Melania Trump a full and speedy recovery. But that does not answer the fundamental question this president will leave behind when he leaves office. What norms survive a man who takes pleasure in destroying norms? Self’s overt commitment to the pursuit of self-derangement and the unchecked development of his independent sensibility mark him as one of the most unusual British writers of his time. His fiction, consisting mostly of satirical novels of the grotesque, is the product of deep-seated literary influences and intellectual orientations. The central reason that a broad perception of Self—who is known for writing books usually shunned as deliberately difficult, verbose, and unreadable—exists in Britain, is his public persona, mainly expressed on television panel shows. Through his great height (6’5”),

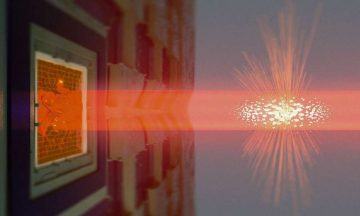

Self’s overt commitment to the pursuit of self-derangement and the unchecked development of his independent sensibility mark him as one of the most unusual British writers of his time. His fiction, consisting mostly of satirical novels of the grotesque, is the product of deep-seated literary influences and intellectual orientations. The central reason that a broad perception of Self—who is known for writing books usually shunned as deliberately difficult, verbose, and unreadable—exists in Britain, is his public persona, mainly expressed on television panel shows. Through his great height (6’5”),  A team of researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, have succeeded in entangling two very different quantum objects. The result has several potential applications in ultra-precise sensing and quantum communication and is now published in Nature Physics.

A team of researchers at the Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, have succeeded in entangling two very different quantum objects. The result has several potential applications in ultra-precise sensing and quantum communication and is now published in Nature Physics.

The selected correspondence between Masham and Locke is fascinating to say the least. One of the exchanges treats the topic of religious enthusiasm. In response to Locke’s dismissal of religious enthusiasm as having no epistemological value, Masham notes that Locke might be thinking too narrowly of enthusiasm and indeed that there appears to be a version of it that readies the mind for reflection — a “Divine Sagacitie which is onely Competible to Persons of Pure and Unspoted Minds and without which Reason is not successful in the Contemplation of the Highest matters” (133-34). In another exchange, Masham presses Locke on how an empiricist can account for the formation of an idea of eternity in a finite human mind. Masham argues that the content of that idea does not represent eternity, but merely finite time repeated; that wouldn’t be an idea of eternity at all (184). Here she is gesturing at her own (Cambridge) Platonism and hinting that there are other entities about which Locke thinks we can reason — for example God — but where Lockean empiricism does not allow us to have ideas of them. Masham argues that at the very least finite minds are pre-formed with dispositions and traces, without which many of our ideas would never take shape (183). A third topic that is prominent in the exchanges between Masham and Locke is the question of whether or not the ethical doctrine of Stoicism can be lived by embodied human beings. For example, Masham says that if Epictetus and others are correct, then “Reason Teaches me . . . to be Contended with the World as it tis, and to make the Best of everything in it” (159).

The selected correspondence between Masham and Locke is fascinating to say the least. One of the exchanges treats the topic of religious enthusiasm. In response to Locke’s dismissal of religious enthusiasm as having no epistemological value, Masham notes that Locke might be thinking too narrowly of enthusiasm and indeed that there appears to be a version of it that readies the mind for reflection — a “Divine Sagacitie which is onely Competible to Persons of Pure and Unspoted Minds and without which Reason is not successful in the Contemplation of the Highest matters” (133-34). In another exchange, Masham presses Locke on how an empiricist can account for the formation of an idea of eternity in a finite human mind. Masham argues that the content of that idea does not represent eternity, but merely finite time repeated; that wouldn’t be an idea of eternity at all (184). Here she is gesturing at her own (Cambridge) Platonism and hinting that there are other entities about which Locke thinks we can reason — for example God — but where Lockean empiricism does not allow us to have ideas of them. Masham argues that at the very least finite minds are pre-formed with dispositions and traces, without which many of our ideas would never take shape (183). A third topic that is prominent in the exchanges between Masham and Locke is the question of whether or not the ethical doctrine of Stoicism can be lived by embodied human beings. For example, Masham says that if Epictetus and others are correct, then “Reason Teaches me . . . to be Contended with the World as it tis, and to make the Best of everything in it” (159). Nonetheless, Cézanne came to Pissarro to unlearn his first style, and, seemingly, to change his mind about Courbet, Manet and Delacroix; or at least about what might be made from them, from their attitudes (their subjects, their stances) and their materials. Provocation in art would give way to patience, to exposure to optical events. The word ‘humble’ which Cézanne chose years later to characterise Pissarro – ‘humble and colossal’, he called him, and perhaps even ‘justified in his anarchist theories’ – sums up a number of things. The way forward for French painting, Cézanne seems to have decided in 1873, was to be found in the style that Monet had built, and to which Pissarro had given his distinctive stamp, in the very years when Cézanne had built his massive contrary to Monet’s lightness and impersonality. (‘Monet, around 1869, he struck the great blow’ was Cézanne’s verdict in retrospect. ‘Monet and Pissarro, the two great masters, the only two.’) The Courbet, Manet and Delacroix in oneself, in other words – and no doubt the three remained heroes – would have to be painted out. Sometime in the winter of 1872-73 (I shall return to this later) Cézanne borrowed a landscape Pissarro had done two years before, in the first heyday of Impressionism, and sat down to copy it stroke by stroke.

Nonetheless, Cézanne came to Pissarro to unlearn his first style, and, seemingly, to change his mind about Courbet, Manet and Delacroix; or at least about what might be made from them, from their attitudes (their subjects, their stances) and their materials. Provocation in art would give way to patience, to exposure to optical events. The word ‘humble’ which Cézanne chose years later to characterise Pissarro – ‘humble and colossal’, he called him, and perhaps even ‘justified in his anarchist theories’ – sums up a number of things. The way forward for French painting, Cézanne seems to have decided in 1873, was to be found in the style that Monet had built, and to which Pissarro had given his distinctive stamp, in the very years when Cézanne had built his massive contrary to Monet’s lightness and impersonality. (‘Monet, around 1869, he struck the great blow’ was Cézanne’s verdict in retrospect. ‘Monet and Pissarro, the two great masters, the only two.’) The Courbet, Manet and Delacroix in oneself, in other words – and no doubt the three remained heroes – would have to be painted out. Sometime in the winter of 1872-73 (I shall return to this later) Cézanne borrowed a landscape Pissarro had done two years before, in the first heyday of Impressionism, and sat down to copy it stroke by stroke. A Supreme Court justice was dead, and the president, in his last year in office, quickly nominated a prominent lawyer to replace him. But the unlucky nominee’s bid was forestalled by the U.S. Senate, blocked due to the hostile politics of the time. It was 1852, but the doomed confirmation battle sounds a lot like 2016. “The nomination of Edward A. Bradford…as successor to Justice McKinley was postponed,” reported the New York Times on September 3, 1852. “This is equivalent to a rejection, contingent upon the result of the pending Presidential election. It is intended to reserve this vacancy to be supplied by Gen. Pierce, provided he be elected.”

A Supreme Court justice was dead, and the president, in his last year in office, quickly nominated a prominent lawyer to replace him. But the unlucky nominee’s bid was forestalled by the U.S. Senate, blocked due to the hostile politics of the time. It was 1852, but the doomed confirmation battle sounds a lot like 2016. “The nomination of Edward A. Bradford…as successor to Justice McKinley was postponed,” reported the New York Times on September 3, 1852. “This is equivalent to a rejection, contingent upon the result of the pending Presidential election. It is intended to reserve this vacancy to be supplied by Gen. Pierce, provided he be elected.” President

President  The translator is a writer. The writer is a translator. How many times have I run up against these assertions?—in a chat between translators protesting because they are not listed in a publisher’s index of authors; or in the work of literary theorists, even poets (“Each text is unique, yet at the same time it is the translation of another text,” observed Octavio Paz). Others claim that because language is referential, any written text is a translation of the world referred to.

The translator is a writer. The writer is a translator. How many times have I run up against these assertions?—in a chat between translators protesting because they are not listed in a publisher’s index of authors; or in the work of literary theorists, even poets (“Each text is unique, yet at the same time it is the translation of another text,” observed Octavio Paz). Others claim that because language is referential, any written text is a translation of the world referred to. There’s something strange about this coronavirus pandemic. Even after months of extensive research by the global scientific community, many questions remain open.

There’s something strange about this coronavirus pandemic. Even after months of extensive research by the global scientific community, many questions remain open.