Neil Fligstein and Steven Vogel in Boston Review:

Neil Fligstein and Steven Vogel in Boston Review:

If anything could have dislodged the neoliberal doctrine of freeing the market from the government, you might have expected the coronavirus pandemic to do the trick. Of course, the same was said about the global financial crisis, which was supposed to transform everything from macroeconomic policy to financial regulation and the social safety net.

Now we are facing a particularly horrifying moment, defined by the triple shock of the Trump presidency, the pandemic, and the economic disasters that followed from it. Perhaps these—if combined with a change in power in the upcoming election—could offer a historic window of opportunity. Perhaps. But seizing the opportunity will require a new kind of political-economic thinking. Instead of starting from a stylized view of how the world ought to work, we should consider what policies have proved effective in different societies experiencing similar challenges. This comparative way of thinking increases the menu of options and may suggest novel solutions to our problems that lie outside the narrow theoretical assumptions of market-fundamentalist neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism implies a one-size-fits-all set of policy solutions: less government and more market, as if the “free market” were a single equilibrium. To the contrary, we know that there have been multiple paths to economic growth and multiple solutions to economic crises in different societies.

More here.

America meant all sorts of things to Lawrence, many of them adumbrated in his Studies in Classic American Literature (1923). In The Bad Side of Books, there’s an essay called “Pan in America” (1924), which starts from the cry that echoed around the Mediterranean as paganism faded: “The Great God Pan is dead!” What that meant, according to Lawrence, was that the possibility of life lived in spontaneous unison with nature dwindled as commerce, technology, and metaphysical religion advanced. Pan seemed still alive to Lawrence in the Indians of the Southwest, and he conjured a graphic account of the animist mind and imagination. But even there, Pan was “dying fast”; every Indian, Lawrence thought, “will kill Pan with his own hands for the sake of a motor car.” Who, given the choice the essay poses—“to live among the living, or to run on wheels”—would choose what Lawrence called “life”? Pretty much no one, he thought, though he returned to this opposition again and again.

America meant all sorts of things to Lawrence, many of them adumbrated in his Studies in Classic American Literature (1923). In The Bad Side of Books, there’s an essay called “Pan in America” (1924), which starts from the cry that echoed around the Mediterranean as paganism faded: “The Great God Pan is dead!” What that meant, according to Lawrence, was that the possibility of life lived in spontaneous unison with nature dwindled as commerce, technology, and metaphysical religion advanced. Pan seemed still alive to Lawrence in the Indians of the Southwest, and he conjured a graphic account of the animist mind and imagination. But even there, Pan was “dying fast”; every Indian, Lawrence thought, “will kill Pan with his own hands for the sake of a motor car.” Who, given the choice the essay poses—“to live among the living, or to run on wheels”—would choose what Lawrence called “life”? Pretty much no one, he thought, though he returned to this opposition again and again. Somewhere within the storerooms of London’s staid, gray-faced Tate Gallery (for it’s currently no longer on exhibit) is an 1834 painting by J.M.W. Turner entitled “The Golden Bough.” Rendered in that painter’s characteristic sfumato of smeared light and smoky color, Turner’s composition depicts a scene from Virgil’s epic

Somewhere within the storerooms of London’s staid, gray-faced Tate Gallery (for it’s currently no longer on exhibit) is an 1834 painting by J.M.W. Turner entitled “The Golden Bough.” Rendered in that painter’s characteristic sfumato of smeared light and smoky color, Turner’s composition depicts a scene from Virgil’s epic  The election is 25 days away, and President Donald Trump’s political prognosis is not good. He’s

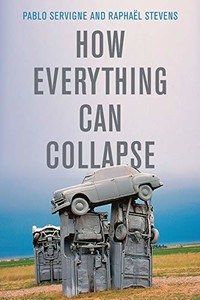

The election is 25 days away, and President Donald Trump’s political prognosis is not good. He’s  “UTOPIA HAS SUDDENLY changed camp,” write Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens in How Everything Can Collapse: A Manual for Our Times, just out in an English translation by Andrew Brown. “Today, the utopian is whoever believes that everything can just keep going as before.” In 2015, when the book was first published in France, such a statement might have sounded alarmist. In 2020, Collapse feels positively prophetic. Things have not kept going as before, and it seems increasingly doubtful that they ever will again.

“UTOPIA HAS SUDDENLY changed camp,” write Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens in How Everything Can Collapse: A Manual for Our Times, just out in an English translation by Andrew Brown. “Today, the utopian is whoever believes that everything can just keep going as before.” In 2015, when the book was first published in France, such a statement might have sounded alarmist. In 2020, Collapse feels positively prophetic. Things have not kept going as before, and it seems increasingly doubtful that they ever will again. Imagine a human society not so very different from our own, on which a cataclysm is about to fall. Thousands, perhaps millions, of people will die. Many others will lead shorter and less happy lives; the financial and human costs will be felt for decades, if not forever. Looking in from the outside, and thinking in terms of big ideas such as equality, justice, fairness, human rights and the rule of law, what kind of society would you want to emerge from this catastrophe? What core principles should lie at its heart?

Imagine a human society not so very different from our own, on which a cataclysm is about to fall. Thousands, perhaps millions, of people will die. Many others will lead shorter and less happy lives; the financial and human costs will be felt for decades, if not forever. Looking in from the outside, and thinking in terms of big ideas such as equality, justice, fairness, human rights and the rule of law, what kind of society would you want to emerge from this catastrophe? What core principles should lie at its heart?

In 1976, twenty-five-year-old Wendy Ewald rented a small house on Ingram Creek in a remote landscape in eastern Kentucky, hoping to make a photographic document of “the soul and rhythm of the place.” As she writes in an essay included in the expanded new edition of Portraits and Dreams: Photographs and Stories By Children of The Appalachians, originally published in 1985, her camera landed on the “commonplaces” of Letcher County. Set in the Cumberland Mountains at the edge of Kentucky and Virginia, Lechter Country is in the rural, rolling, rugged, coal-mining heart of the still sprawling and still vastly misunderstood and frequently mispronounced region known as Appalachia (the correct pronunciation is Appa-LATCH-uh). More than a decade before Ewald’s arrival, the publication of Night Comes to the Cumberlands: A Biography of a Depressed Area, by local lawyer and environmental crusader Harry Caudill, had helped spur John F. Kennedy and later Lyndon B. Johnson to declare war on poverty in Letcher County and regions like it. But Ewald did not intend to photograph “poverty,” or to photograph the place in the reductive way it had come to be depicted. She was interested in the way the people pictured themselves.

In 1976, twenty-five-year-old Wendy Ewald rented a small house on Ingram Creek in a remote landscape in eastern Kentucky, hoping to make a photographic document of “the soul and rhythm of the place.” As she writes in an essay included in the expanded new edition of Portraits and Dreams: Photographs and Stories By Children of The Appalachians, originally published in 1985, her camera landed on the “commonplaces” of Letcher County. Set in the Cumberland Mountains at the edge of Kentucky and Virginia, Lechter Country is in the rural, rolling, rugged, coal-mining heart of the still sprawling and still vastly misunderstood and frequently mispronounced region known as Appalachia (the correct pronunciation is Appa-LATCH-uh). More than a decade before Ewald’s arrival, the publication of Night Comes to the Cumberlands: A Biography of a Depressed Area, by local lawyer and environmental crusader Harry Caudill, had helped spur John F. Kennedy and later Lyndon B. Johnson to declare war on poverty in Letcher County and regions like it. But Ewald did not intend to photograph “poverty,” or to photograph the place in the reductive way it had come to be depicted. She was interested in the way the people pictured themselves.

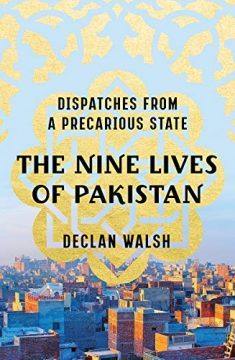

Declan Walsh begins his captivating new book on Pakistan with an account of how he came to leave the country for the first time, abruptly and involuntarily in May 2013. “The angels came to spirit me away,” is the way he puts it, using the Urdu slang for the all-powerful men of the

Declan Walsh begins his captivating new book on Pakistan with an account of how he came to leave the country for the first time, abruptly and involuntarily in May 2013. “The angels came to spirit me away,” is the way he puts it, using the Urdu slang for the all-powerful men of the  In Stanford in 2008, the Irish poet Eavan Boland told me how much she admired the work of

In Stanford in 2008, the Irish poet Eavan Boland told me how much she admired the work of  Since Nature’s earliest issues, we have been publishing news, commentary and primary research on science and politics. But why does a journal of science need to cover politics? It’s an important question that readers often ask.

Since Nature’s earliest issues, we have been publishing news, commentary and primary research on science and politics. But why does a journal of science need to cover politics? It’s an important question that readers often ask. AC: I need to rephrase this question slightly in order to answer it. “Moral realism” is a label that I deliberately don’t use in describing my image of ethics. Not that, abstractly considered, the term is obviously ill-suited to capture things I believe. It is, for instance, a conviction of mine that that there are morally salient aspects of the world that as such lend themselves to empirical discovery. A case could easily be made for speaking of moral realism in this connection. But that would likely generate confusion. When I claim that, say, humans and animals have moral qualities that are as such observable, I work with an understanding of what the world is like, and of what is involved in knowing it, that is foreign to familiar discussions of moral realism. These discussions are often structured by the assumption that objectivity excludes anything that is only adequately conceivable in terms of reference to human subjectivity. Moral realism is frequently envisioned as an improbable position on which moral values are objective in this subjectivity-extruding sense while still somehow having a direct bearing on action and choice. Thus does the specter of Mackie’s “argument from queerness” still haunt the halls of moral philosophy.

AC: I need to rephrase this question slightly in order to answer it. “Moral realism” is a label that I deliberately don’t use in describing my image of ethics. Not that, abstractly considered, the term is obviously ill-suited to capture things I believe. It is, for instance, a conviction of mine that that there are morally salient aspects of the world that as such lend themselves to empirical discovery. A case could easily be made for speaking of moral realism in this connection. But that would likely generate confusion. When I claim that, say, humans and animals have moral qualities that are as such observable, I work with an understanding of what the world is like, and of what is involved in knowing it, that is foreign to familiar discussions of moral realism. These discussions are often structured by the assumption that objectivity excludes anything that is only adequately conceivable in terms of reference to human subjectivity. Moral realism is frequently envisioned as an improbable position on which moral values are objective in this subjectivity-extruding sense while still somehow having a direct bearing on action and choice. Thus does the specter of Mackie’s “argument from queerness” still haunt the halls of moral philosophy. India first started using pellet-firing shotguns against Kashmiris in 2010 but the matter only hit international prominence in 2016 when protests following the death of Burhan Wani resulted in thousands of injuries, the blinding of hundreds and the deaths of over 70 people.

India first started using pellet-firing shotguns against Kashmiris in 2010 but the matter only hit international prominence in 2016 when protests following the death of Burhan Wani resulted in thousands of injuries, the blinding of hundreds and the deaths of over 70 people.