Traci Watson in Nature:

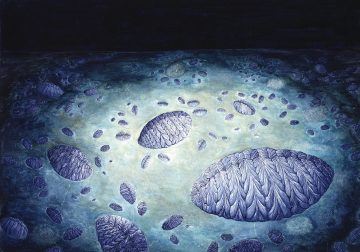

The revolutionary animal lived and died in the muck. In its final hours, it inched across the sea floor, leaving a track like a tyre print, and finally went still. Then geology set to work. Over the next half a billion years, sediment turned to stone, preserving the deathbed scene. The fossilized creature looks like a piece of frayed rope measuring just a few centimetres wide. But it was a trailblazer among living things. This was the earliest-known animal to show unequivocal evidence of two momentous innovations packaged together: the ability to roam the ocean floor, and a body built from segments. It was also among the oldest known to have clear front and back ends, and a left side that mirrored its right. Those same features are found today in animals from flies to flying foxes, from lobsters to lions.

The revolutionary animal lived and died in the muck. In its final hours, it inched across the sea floor, leaving a track like a tyre print, and finally went still. Then geology set to work. Over the next half a billion years, sediment turned to stone, preserving the deathbed scene. The fossilized creature looks like a piece of frayed rope measuring just a few centimetres wide. But it was a trailblazer among living things. This was the earliest-known animal to show unequivocal evidence of two momentous innovations packaged together: the ability to roam the ocean floor, and a body built from segments. It was also among the oldest known to have clear front and back ends, and a left side that mirrored its right. Those same features are found today in animals from flies to flying foxes, from lobsters to lions.

Palaeontologist Shuhai Xiao marvels at the tracks left by this creature, Yilingia spiciformis, and how they captured evidence of its movement. In his cluttered office at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, he shows off a slab of beige resin — a reproduction of the fossil, which was found in China’s Yangtze Gorges region and is now kept in a Chinese research institute. The replica captures a snapshot of a moment from 550 million years ago. Xiao, whose team formally described Yilingia last year1, traces the bumpy tracks it made immediately before its death. “It was just moving around, and it died suddenly,” he says.

More here.

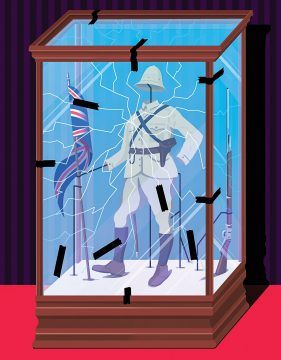

On a cloud-spackled Sunday last June, protesters in Bristol, England, gathered at a statue of Edward Colston, a seventeenth-century slave trader on whose watch more than eighty thousand Africans were trafficked across the Atlantic. “Pull it down!” the crowd chanted, as people yanked on a rope around the statue’s neck. A few tugs, and the figure clanged off its pedestal. A panel of its coat skirt cracked off to expose a hollow buttock as the demonstrators rolled the statue toward the harbor, a few hundred yards away, and then tipped it headlong into the water.

On a cloud-spackled Sunday last June, protesters in Bristol, England, gathered at a statue of Edward Colston, a seventeenth-century slave trader on whose watch more than eighty thousand Africans were trafficked across the Atlantic. “Pull it down!” the crowd chanted, as people yanked on a rope around the statue’s neck. A few tugs, and the figure clanged off its pedestal. A panel of its coat skirt cracked off to expose a hollow buttock as the demonstrators rolled the statue toward the harbor, a few hundred yards away, and then tipped it headlong into the water. And yet, despite his shifting placement in the dynamic force field of cultural politics, Steiner resisted turning into a curmudgeonly apologist for a world on the wane or allowing his Kulturpessimismus to sanction a resentful withdrawal from the public arena. In fact, one of the hallmarks of his career was a willingness to remain suspended within paradoxes, never forcing a simple choice between unpalatable options. This attitude was already evident in Language and Silence, which both celebrates humanistic high culture and acknowledges that the Holocaust has disabused us of the naïve illusion that it humanizes those who uphold it. Or as he put it in what is perhaps his most frequently cited sentences: “We come after. We know now that a man can read Goethe or Rilke in the evening, that he can play Bach or Schubert, and go to his day’s work at Auschwitz in the morning.”

And yet, despite his shifting placement in the dynamic force field of cultural politics, Steiner resisted turning into a curmudgeonly apologist for a world on the wane or allowing his Kulturpessimismus to sanction a resentful withdrawal from the public arena. In fact, one of the hallmarks of his career was a willingness to remain suspended within paradoxes, never forcing a simple choice between unpalatable options. This attitude was already evident in Language and Silence, which both celebrates humanistic high culture and acknowledges that the Holocaust has disabused us of the naïve illusion that it humanizes those who uphold it. Or as he put it in what is perhaps his most frequently cited sentences: “We come after. We know now that a man can read Goethe or Rilke in the evening, that he can play Bach or Schubert, and go to his day’s work at Auschwitz in the morning.”

Agatha Christie was in her mid-20s when, in 1916, she took up what seemed the improbable endeavor of penning her first detective novel. It was so unlikely, in fact, that her elder sister, Madge, with whom she had always competed, dared Agatha to accomplish the feat, certain of her sibling’s eventual failure.

Agatha Christie was in her mid-20s when, in 1916, she took up what seemed the improbable endeavor of penning her first detective novel. It was so unlikely, in fact, that her elder sister, Madge, with whom she had always competed, dared Agatha to accomplish the feat, certain of her sibling’s eventual failure. On his first day as the new science director for the Monterey Bay Aquarium in

On his first day as the new science director for the Monterey Bay Aquarium in  Senator John Cornyn of Texas, locked in his own tight re-election race, recently told the local media that he, too, has disagreed with Mr. Trump on numerous issues, including deficit spending, trade policy and his raiding of the defense budget. Mr. Cornyn said he opted to keep his opposition private rather than get into a public tiff with Mr. Trump “because, as I’ve observed, those usually don’t end too well.”

Senator John Cornyn of Texas, locked in his own tight re-election race, recently told the local media that he, too, has disagreed with Mr. Trump on numerous issues, including deficit spending, trade policy and his raiding of the defense budget. Mr. Cornyn said he opted to keep his opposition private rather than get into a public tiff with Mr. Trump “because, as I’ve observed, those usually don’t end too well.” In Alysson Muotri’s laboratory, hundreds of miniature human brains, the size of sesame seeds, float in Petri dishes, sparking with electrical activity. These tiny structures, known as brain organoids, are grown from human stem cells and have become a familiar fixture in many labs that study the properties of the brain. Muotri, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), has found some unusual ways to deploy his. He has connected organoids to walking robots, modified their genomes with Neanderthal genes, launched them into orbit aboard the International Space Station, and used them as models to develop more human-like artificial-intelligence systems. Like many scientists, Muotri has temporarily pivoted to studying COVID-19, using brain organoids to test

In Alysson Muotri’s laboratory, hundreds of miniature human brains, the size of sesame seeds, float in Petri dishes, sparking with electrical activity. These tiny structures, known as brain organoids, are grown from human stem cells and have become a familiar fixture in many labs that study the properties of the brain. Muotri, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), has found some unusual ways to deploy his. He has connected organoids to walking robots, modified their genomes with Neanderthal genes, launched them into orbit aboard the International Space Station, and used them as models to develop more human-like artificial-intelligence systems. Like many scientists, Muotri has temporarily pivoted to studying COVID-19, using brain organoids to test  Back on planet Earth, in the show itself there is no limitless space-time, just a succession of powerful slabs of Nauman in which he swaps techniques, changes methods, explores materials, alternates moments of peace with bouts of heavy slapping, and never lets up in a madcap journey of artistic exploration usually set in darkness.

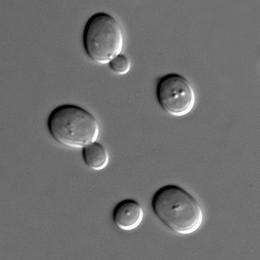

Back on planet Earth, in the show itself there is no limitless space-time, just a succession of powerful slabs of Nauman in which he swaps techniques, changes methods, explores materials, alternates moments of peace with bouts of heavy slapping, and never lets up in a madcap journey of artistic exploration usually set in darkness. In the past two decades, researchers have shown that biological traits in both species and individual cells can be shaped by the environment and inherited even without gene mutations, an outcome that contradicts one of the classical interpretations of Darwinian theory. But exactly how these epigenetic, or non-genetic, traits are inherited has been unclear. Now, in a study published Oct. 27 in the journal Cell Reports, Yale scientists show how

In the past two decades, researchers have shown that biological traits in both species and individual cells can be shaped by the environment and inherited even without gene mutations, an outcome that contradicts one of the classical interpretations of Darwinian theory. But exactly how these epigenetic, or non-genetic, traits are inherited has been unclear. Now, in a study published Oct. 27 in the journal Cell Reports, Yale scientists show how  In Search of the Soul presupposes less sympathy for religion on the part of its readers than Why Believe? and How to Believe do. Nonetheless, at just about the middle of the text, Cottingham proposes that “something like a traditional theistic worldview offer[s] a more hospitable framework” for the problems under consideration than does the “materialist consensus” among many philosophers and growing numbers of “nones.” Cottingham’s work consistently exhibits great respect for the findings of the sciences. As he bluntly writes in How to Believe, “there is no future for a religious or any other outlook that tries to contradict or set aside the findings of science.” “We must start from the nature of the universe as we find it,” he states in Why Believe?—and part of what we have found from the “spectacular success” of modern science is that there is “no possibility of a return to an animistic or mythological framework for understanding the world.” There are, however, limits to scientific explanation: most fundamentally, science cannot explain why the laws of nature are what they are. In David Hume’s words, modern science does not inquire into nature’s “ultimate springs and principles.” In Search of the Soul focuses on two problems that resist scientific explanation. First, the fact that “the conscious lifeworld of the individual subject,” though realized in and through the material properties of the human body, isn’t captured by an account of those properties (the “problem of consciousness”). And second, “the fact that moral values and obligations exert an authoritative demand on us, whether we like it or not” (what philosophers call the problem of “strong normativity”). For Cottingham, theism is an interpretive framework—a favorite phrase of his—that can accommodate those problems.

In Search of the Soul presupposes less sympathy for religion on the part of its readers than Why Believe? and How to Believe do. Nonetheless, at just about the middle of the text, Cottingham proposes that “something like a traditional theistic worldview offer[s] a more hospitable framework” for the problems under consideration than does the “materialist consensus” among many philosophers and growing numbers of “nones.” Cottingham’s work consistently exhibits great respect for the findings of the sciences. As he bluntly writes in How to Believe, “there is no future for a religious or any other outlook that tries to contradict or set aside the findings of science.” “We must start from the nature of the universe as we find it,” he states in Why Believe?—and part of what we have found from the “spectacular success” of modern science is that there is “no possibility of a return to an animistic or mythological framework for understanding the world.” There are, however, limits to scientific explanation: most fundamentally, science cannot explain why the laws of nature are what they are. In David Hume’s words, modern science does not inquire into nature’s “ultimate springs and principles.” In Search of the Soul focuses on two problems that resist scientific explanation. First, the fact that “the conscious lifeworld of the individual subject,” though realized in and through the material properties of the human body, isn’t captured by an account of those properties (the “problem of consciousness”). And second, “the fact that moral values and obligations exert an authoritative demand on us, whether we like it or not” (what philosophers call the problem of “strong normativity”). For Cottingham, theism is an interpretive framework—a favorite phrase of his—that can accommodate those problems.

A basic truth is once again trying to break through the agony of worldwide pandemic and the enduring inhumanity of racist oppression. Healthcare workers risking their lives for others, mutual aid networks empowering neighbourhoods, farmers delivering food to quarantined customers, mothers forming lines to protect youth from police violence: we’re in this life together. We – young and old, citizen and immigrant – do best when we collaborate. Indeed, our only way to survive is to have each other’s back while safeguarding the resilience and diversity of this planet we call home.

A basic truth is once again trying to break through the agony of worldwide pandemic and the enduring inhumanity of racist oppression. Healthcare workers risking their lives for others, mutual aid networks empowering neighbourhoods, farmers delivering food to quarantined customers, mothers forming lines to protect youth from police violence: we’re in this life together. We – young and old, citizen and immigrant – do best when we collaborate. Indeed, our only way to survive is to have each other’s back while safeguarding the resilience and diversity of this planet we call home. Erwin Schrödinger’s famous book What Is Life? highlighted the connections between physics, and thermodynamics in particular, and the nature of living beings. But the exact connections between living organisms and the flow of heat and entropy remains a topic of ongoing research. Jeremy England is a leader in this field, deriving connections between thermodynamic relations and the processes of life. He is also an ordained rabbi who finds resonances between modern science and passages in the Hebrew Bible. We talk about it all, from entropy fluctuation theorems to how scientists should approach religion.

Erwin Schrödinger’s famous book What Is Life? highlighted the connections between physics, and thermodynamics in particular, and the nature of living beings. But the exact connections between living organisms and the flow of heat and entropy remains a topic of ongoing research. Jeremy England is a leader in this field, deriving connections between thermodynamic relations and the processes of life. He is also an ordained rabbi who finds resonances between modern science and passages in the Hebrew Bible. We talk about it all, from entropy fluctuation theorems to how scientists should approach religion. Most Americans never encounter the simple, brute fact of U.S. military supremacy. Bases are far away; wars in remote places are waged remotely; amid the general fragmentation of social life, those who serve in the military are lumped into particular demographic niches. But on the rare occasions when Americans do think about their military, they are remarkably supportive. The military routinely ranks as the

Most Americans never encounter the simple, brute fact of U.S. military supremacy. Bases are far away; wars in remote places are waged remotely; amid the general fragmentation of social life, those who serve in the military are lumped into particular demographic niches. But on the rare occasions when Americans do think about their military, they are remarkably supportive. The military routinely ranks as the  By bringing attention to the very first encounters with uncertainty in early rabbinic literature (the Mishna and Tosefta), Halbertal insightfully demonstrates the ways in which early Jewish legal authorities were keenly interested in “demarcate[ing] and limit[ing] the destabilizing power of doubt and fear of uncertainty.” The heaps of laws surrounding states of uncertainty – which Halbertal correctly describes as some of the most complex areas of Jewish law – were not designed, by virtue of their sheer volume and complexity, to increase anxiety but to quell it. Early rabbinic engagement with doubt was thus an expression of liberation, not legal bondage. Its intent was not to compound hair-splitting laws on top of likely never-to-be-experienced hypotheticals for the sake of burdening Jews with laws where none previously existed, thereby adding to their already extensive repertoire of rules. Rather, this complex system was intended to free up the Jewish practitioner.

By bringing attention to the very first encounters with uncertainty in early rabbinic literature (the Mishna and Tosefta), Halbertal insightfully demonstrates the ways in which early Jewish legal authorities were keenly interested in “demarcate[ing] and limit[ing] the destabilizing power of doubt and fear of uncertainty.” The heaps of laws surrounding states of uncertainty – which Halbertal correctly describes as some of the most complex areas of Jewish law – were not designed, by virtue of their sheer volume and complexity, to increase anxiety but to quell it. Early rabbinic engagement with doubt was thus an expression of liberation, not legal bondage. Its intent was not to compound hair-splitting laws on top of likely never-to-be-experienced hypotheticals for the sake of burdening Jews with laws where none previously existed, thereby adding to their already extensive repertoire of rules. Rather, this complex system was intended to free up the Jewish practitioner.