Sydney Ladensohn Stern in Literary Hub:

On December 4, Netflix subscribers will start streaming Mank, David Fincher’s biopic about Herman Mankiewicz, the Hollywood screenwriter who wrote the original script for Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. Mank is a cinematic feast that requires neither familiarity with Herman Mankiewicz nor prior exposure to Citizen Kane to enjoy it. But as with most works of complexity, the more one brings to it, the richer the experience. As it happens, I bring a great deal. I call it knowledge. The less charitable might call it obsession.

On December 4, Netflix subscribers will start streaming Mank, David Fincher’s biopic about Herman Mankiewicz, the Hollywood screenwriter who wrote the original script for Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. Mank is a cinematic feast that requires neither familiarity with Herman Mankiewicz nor prior exposure to Citizen Kane to enjoy it. But as with most works of complexity, the more one brings to it, the richer the experience. As it happens, I bring a great deal. I call it knowledge. The less charitable might call it obsession.

I spent the last decade researching and writing a dual biography of Herman and his younger, more successful brother, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, writer/director of, among others, the classic All About Eve and the notorious Cleopatra. Before he became a screenwriter, Herman was a New York newspaperman, a celebrated wit and Algonquin group habitué, a theatre critic for the New York Times and New Yorker, and a playwright collaborating with George S. Kaufman. Unfortunately, Herman was also an alcoholic and chronic gambler. He originally went to Hollywood in 1925 for a short writing assignment, intending to work there just long enough to pay off a gambling debt. Instead, he stayed for the rest of his life, despising the movie business but never managing to leave it. He drank himself to death in 1953 at the age of 55.

More here.

The best thing about David Fincher’s new film, “Mank,” is that it isn’t about what one expects it to be about. More specifically, the movie (which is streaming on Netflix) is not about the assertion, made most strenuously by Pauline Kael in her controversial New Yorker piece “

The best thing about David Fincher’s new film, “Mank,” is that it isn’t about what one expects it to be about. More specifically, the movie (which is streaming on Netflix) is not about the assertion, made most strenuously by Pauline Kael in her controversial New Yorker piece “ IN HER MEMOIR

IN HER MEMOIR Over at his

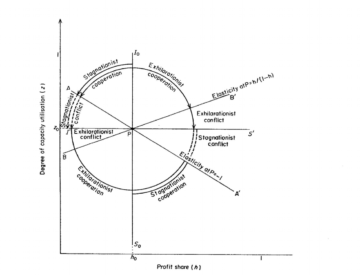

Over at his  Maya Adereth interviews Amit Bhaduri in Phenomenal World:

Maya Adereth interviews Amit Bhaduri in Phenomenal World: I

I There’s plenty wrong with rights, Nigel Biggar tells us, as some very powerful thinkers have been saying since the ‘rights of man and of the citizen’ first entered the lexicon of mass democratic politics during the French Revolution. This sceptical tradition has been particularly strong in Britain, a country that likes to think it invented rights at Runnymede. It runs from Edmund Burke, through Jeremy Bentham (who called natural rights ‘nonsense on stilts’) right up to contemporary figures like Jonathan Sumption, a former justice of the UK Supreme Court, and the philosopher Onora O’Neill.

There’s plenty wrong with rights, Nigel Biggar tells us, as some very powerful thinkers have been saying since the ‘rights of man and of the citizen’ first entered the lexicon of mass democratic politics during the French Revolution. This sceptical tradition has been particularly strong in Britain, a country that likes to think it invented rights at Runnymede. It runs from Edmund Burke, through Jeremy Bentham (who called natural rights ‘nonsense on stilts’) right up to contemporary figures like Jonathan Sumption, a former justice of the UK Supreme Court, and the philosopher Onora O’Neill. The

The As a child, Suzanne Simard often roamed Canada’s old-growth forests with her siblings, building forts from fallen branches, foraging mushrooms and huckleberries and occasionally eating handfuls of dirt (she liked the taste). Her grandfather and uncles, meanwhile, worked nearby as horse loggers, using low-impact methods to selectively harvest cedar, Douglas fir and white pine. They took so few trees that Simard never noticed much of a difference. The forest seemed ageless and infinite, pillared with conifers, jeweled with raindrops and brimming with ferns and fairy bells. She experienced it as “nature in the raw” — a mythic realm, perfect as it was. When she began attending the University of British Columbia, she was elated to discover forestry: an entire field of science devoted to her beloved domain. It seemed like the natural choice.

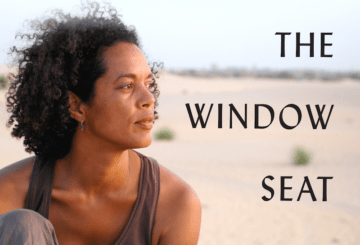

As a child, Suzanne Simard often roamed Canada’s old-growth forests with her siblings, building forts from fallen branches, foraging mushrooms and huckleberries and occasionally eating handfuls of dirt (she liked the taste). Her grandfather and uncles, meanwhile, worked nearby as horse loggers, using low-impact methods to selectively harvest cedar, Douglas fir and white pine. They took so few trees that Simard never noticed much of a difference. The forest seemed ageless and infinite, pillared with conifers, jeweled with raindrops and brimming with ferns and fairy bells. She experienced it as “nature in the raw” — a mythic realm, perfect as it was. When she began attending the University of British Columbia, she was elated to discover forestry: an entire field of science devoted to her beloved domain. It seemed like the natural choice. Tumbuktu, Tehran, London, Freetown, Honolulu, New Orleans. These are but a few of the compass points visited in

Tumbuktu, Tehran, London, Freetown, Honolulu, New Orleans. These are but a few of the compass points visited in  For the first time, a quantum computer made from photons—particles of light—has outperformed even the fastest classical supercomputers.

For the first time, a quantum computer made from photons—particles of light—has outperformed even the fastest classical supercomputers. Adam Smith

Adam Smith