Montana Ray at The Point:

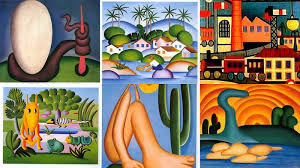

The Confederate immigrants didn’t impose their way of life in São Paulo’s rural interior. On neighboring plantations, enslaved women were raising the white artists who would become the country’s major modernists. Brazil’s most famous modernist painter, Tarsila do Amaral, muse of Antropofagia, grew up on her family’s coffee plantation, a half hour’s drive from the American colony. Antropofagia was a movement of “cultural cannibalism” based on a caricature of the Tupi indigenous people as cannibals; elite white Brazilians would “cannibalize” French styles in the production of Brazilian subject matter: Black people. A year before her death, do Amaral explained that the subject for her first anthropophagic painting, A Negra (1923), was a “female slave” she remembered from her youth, and described in vivid detail I won’t repeat how the woman had stretched her breasts so that she might breastfeed while working. Chattel slavery legally ended in Brazil on May 13, 1888, when do Amaral was one year old, so her explanation was technically anachronistic. Either emancipation passed without notice, or her family’s plantation hummed along under a new economic arrangement so closely resembling slavery that she still referred to wage workers as “slaves.”

The Confederate immigrants didn’t impose their way of life in São Paulo’s rural interior. On neighboring plantations, enslaved women were raising the white artists who would become the country’s major modernists. Brazil’s most famous modernist painter, Tarsila do Amaral, muse of Antropofagia, grew up on her family’s coffee plantation, a half hour’s drive from the American colony. Antropofagia was a movement of “cultural cannibalism” based on a caricature of the Tupi indigenous people as cannibals; elite white Brazilians would “cannibalize” French styles in the production of Brazilian subject matter: Black people. A year before her death, do Amaral explained that the subject for her first anthropophagic painting, A Negra (1923), was a “female slave” she remembered from her youth, and described in vivid detail I won’t repeat how the woman had stretched her breasts so that she might breastfeed while working. Chattel slavery legally ended in Brazil on May 13, 1888, when do Amaral was one year old, so her explanation was technically anachronistic. Either emancipation passed without notice, or her family’s plantation hummed along under a new economic arrangement so closely resembling slavery that she still referred to wage workers as “slaves.”

more here.

Samuel Johnson famously remarked, ‘It is commonly observed, that when two Englishmen meet, their first talk is of the weather; they are in haste to tell each other, what each must already know.’ Virginia Woolf politely added that Englishwomen also talk about the weather but thought there should be strict rules attached to all such discussions. A hostess or a novelist might talk about the weather to settle a guest or a reader, but they should move swiftly on to more interesting themes. A novel that considers nothing but the weather was most probably written by Arnold Bennett (I paraphrase). Mark Twain took this further, promising in the opening of The American Claimant that ‘no weather will be found in this book’ as ‘it is plain that persistent intrusions of weather are bad for both reader and author’.

Samuel Johnson famously remarked, ‘It is commonly observed, that when two Englishmen meet, their first talk is of the weather; they are in haste to tell each other, what each must already know.’ Virginia Woolf politely added that Englishwomen also talk about the weather but thought there should be strict rules attached to all such discussions. A hostess or a novelist might talk about the weather to settle a guest or a reader, but they should move swiftly on to more interesting themes. A novel that considers nothing but the weather was most probably written by Arnold Bennett (I paraphrase). Mark Twain took this further, promising in the opening of The American Claimant that ‘no weather will be found in this book’ as ‘it is plain that persistent intrusions of weather are bad for both reader and author’. Given that

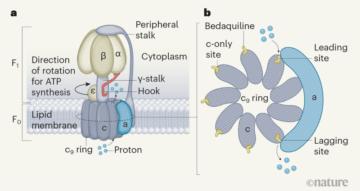

Given that  The 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for the development of an imaging method called cryo-electron microscopy. On bestowing the prize, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences stated that this technique has “moved biochemistry into a new era”.

The 2017 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded for the development of an imaging method called cryo-electron microscopy. On bestowing the prize, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences stated that this technique has “moved biochemistry into a new era”.

“Surely, after 62 years, we should have an exact formulation of some serious part of quantum mechanics?” wrote the eminent Northern Irish physicist John Bell in the opening salvo of his Physics World article, “

“Surely, after 62 years, we should have an exact formulation of some serious part of quantum mechanics?” wrote the eminent Northern Irish physicist John Bell in the opening salvo of his Physics World article, “ For many conservative pundits, the election of Donald Trump marked the moment when the Republican Party abandoned its longstanding claim to being the “party of ideas.” For example, in June 2017 longtime Republican policy advisor Bruce Bartlett wrote, “Trump is what happens when a political party abandons ideas.” For Bartlett, though, it had been a long decline, dating back decades. Likewise, Washington Post columnist Catherine Rampell argued that “somehow the Party of Ideas stopped coming up with them circa, oh, 1987.”

For many conservative pundits, the election of Donald Trump marked the moment when the Republican Party abandoned its longstanding claim to being the “party of ideas.” For example, in June 2017 longtime Republican policy advisor Bruce Bartlett wrote, “Trump is what happens when a political party abandons ideas.” For Bartlett, though, it had been a long decline, dating back decades. Likewise, Washington Post columnist Catherine Rampell argued that “somehow the Party of Ideas stopped coming up with them circa, oh, 1987.” Back in 2013, another in a long line of tussles over scientism broke out. Leon Wieseltier, literary editor of The New Republic,

Back in 2013, another in a long line of tussles over scientism broke out. Leon Wieseltier, literary editor of The New Republic,  Could there possibly be an upside to the long, stressful periods of isolation that so many people have endured during the pandemic lockdown of 2020? When we emerge, will we see the world in a new way? Could there even be a silver lining to these months of quiet living and self-reflection?

Could there possibly be an upside to the long, stressful periods of isolation that so many people have endured during the pandemic lockdown of 2020? When we emerge, will we see the world in a new way? Could there even be a silver lining to these months of quiet living and self-reflection? Léger keeps trying to break away from her mother’s story by scrutinizing the lives of other women, but the maternal shadow—no matter how much she turns away from it—keeps edging into the frame. At their core, these books are about involuntary attention, the subjects we can’t help returning to: Léger tries to write about the Countess of Castiglione and ends up writing about her father’s mistress; she tries to write about Wanda’s divorce and ends up writing about her mother’s; she tries to write about a murdered artist and ends up confronting—finally and fully—her mother’s shame. It is as if every time she picks up a guitar to play, the sounds of a woman’s sobbing emerge from the strings instead. “Only in unfamiliar bedrooms do we perceive with such clarity the true nature of our existence—true because astray,” Léger muses, and by the beginning of The White Dress, the author seems to have accepted that she will always be haunted by backstory: “You must return to one of those unanswered questions, in a room off to the side, you switch on the light and the question is poised there, waiting.” Even when you can’t bring yourself to stare directly at the primal wound, you can’t escape it entirely—and often find yourself, as Léger describes Loden, “a woman telling her own story through that of another woman.” Léger’s own triptych does this as well—following the stories of these other women’s lives into a suite of unfamiliar bedrooms that eventually return her to the aching questions of her own childhood, poised there, waiting.

Léger keeps trying to break away from her mother’s story by scrutinizing the lives of other women, but the maternal shadow—no matter how much she turns away from it—keeps edging into the frame. At their core, these books are about involuntary attention, the subjects we can’t help returning to: Léger tries to write about the Countess of Castiglione and ends up writing about her father’s mistress; she tries to write about Wanda’s divorce and ends up writing about her mother’s; she tries to write about a murdered artist and ends up confronting—finally and fully—her mother’s shame. It is as if every time she picks up a guitar to play, the sounds of a woman’s sobbing emerge from the strings instead. “Only in unfamiliar bedrooms do we perceive with such clarity the true nature of our existence—true because astray,” Léger muses, and by the beginning of The White Dress, the author seems to have accepted that she will always be haunted by backstory: “You must return to one of those unanswered questions, in a room off to the side, you switch on the light and the question is poised there, waiting.” Even when you can’t bring yourself to stare directly at the primal wound, you can’t escape it entirely—and often find yourself, as Léger describes Loden, “a woman telling her own story through that of another woman.” Léger’s own triptych does this as well—following the stories of these other women’s lives into a suite of unfamiliar bedrooms that eventually return her to the aching questions of her own childhood, poised there, waiting. When Michel Leiris died, in 1990, at the age of eighty-nine, the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss wrote, in Libération, that Leiris was “indisputably one of the great writers of the century.” That would seem to be a big claim, especially if the name Leiris meant nothing to you. What was so great about him? The anthropologist Aleksandar Bošković wrote, in 2003, that “there is perhaps no single figure that influenced so strongly French ethnology and anthropology.” This is one Leiris. But, Bošković wrote, Leiris was also an “artist, poet, writer, critic, traveller, surrealist . . . a true ‘Renaissance Man’ whose friends included Breton, Bataille, Giacometti, Picasso, Césaire, and Métraux.” This gets us closer.

When Michel Leiris died, in 1990, at the age of eighty-nine, the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss wrote, in Libération, that Leiris was “indisputably one of the great writers of the century.” That would seem to be a big claim, especially if the name Leiris meant nothing to you. What was so great about him? The anthropologist Aleksandar Bošković wrote, in 2003, that “there is perhaps no single figure that influenced so strongly French ethnology and anthropology.” This is one Leiris. But, Bošković wrote, Leiris was also an “artist, poet, writer, critic, traveller, surrealist . . . a true ‘Renaissance Man’ whose friends included Breton, Bataille, Giacometti, Picasso, Césaire, and Métraux.” This gets us closer. In the 17th century, two Portuguese priests named Sebastião Rodrigues and Francisco Garrpe are faced with a devastating moral dilemma. For the past few weeks, they have been living among a village of Japanese peasants, not far from Nagasaki. The peasants are secretly Christians, and Christianity has been outlawed in Japan. Now an informer in the village has gotten the ear of the state, and the state has demanded hostages. The daimyo (a local feudal lord) will continue to take, cross-examine, and imprison villagers unless someone confesses to either practicing Christianity or hiding the priests. Two of the village’s most revered leaders, Mokichi and Ichizo, volunteer themselves as the first hostages, but don’t know what they should do when put before the authorities. What if they are told to apostatize, they ask, by trampling upon a fumi-e, a stone image of Jesus Christ? Rodrigues, his heart swelling with pity, shouts: “Trample! Trample!” He is immediately reproached by his companion Garrpe, but the essential conflict remains. How can these two priests stand firm in their faith when doing so endangers the very Christian souls that they purport to serve?

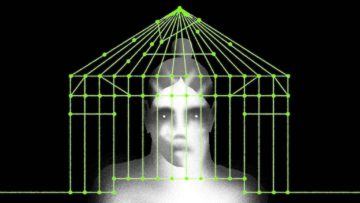

In the 17th century, two Portuguese priests named Sebastião Rodrigues and Francisco Garrpe are faced with a devastating moral dilemma. For the past few weeks, they have been living among a village of Japanese peasants, not far from Nagasaki. The peasants are secretly Christians, and Christianity has been outlawed in Japan. Now an informer in the village has gotten the ear of the state, and the state has demanded hostages. The daimyo (a local feudal lord) will continue to take, cross-examine, and imprison villagers unless someone confesses to either practicing Christianity or hiding the priests. Two of the village’s most revered leaders, Mokichi and Ichizo, volunteer themselves as the first hostages, but don’t know what they should do when put before the authorities. What if they are told to apostatize, they ask, by trampling upon a fumi-e, a stone image of Jesus Christ? Rodrigues, his heart swelling with pity, shouts: “Trample! Trample!” He is immediately reproached by his companion Garrpe, but the essential conflict remains. How can these two priests stand firm in their faith when doing so endangers the very Christian souls that they purport to serve? Credit scores have been used for decades to assess consumer creditworthiness, but their scope is far greater now that they are powered by algorithms: not only do they consider vastly more data, in both volume and type, but they increasingly affect whether you can buy a car, rent an apartment, or get a full-time job. Their comprehensive influence means that if your score is ruined, it can be nearly impossible to recover. Worse, the algorithms are owned by private companies that don’t divulge how they come to their decisions. Victims can be sent in a downward spiral that sometimes ends in homelessness or a return to their abuser.

Credit scores have been used for decades to assess consumer creditworthiness, but their scope is far greater now that they are powered by algorithms: not only do they consider vastly more data, in both volume and type, but they increasingly affect whether you can buy a car, rent an apartment, or get a full-time job. Their comprehensive influence means that if your score is ruined, it can be nearly impossible to recover. Worse, the algorithms are owned by private companies that don’t divulge how they come to their decisions. Victims can be sent in a downward spiral that sometimes ends in homelessness or a return to their abuser. How have a relative handful of billionaires – whose

How have a relative handful of billionaires – whose