Category: Recommended Reading

Between the sacred and the secular

Peter Gordon in New Spectator:

Marxism has had a long and troubled relationship with religion. In 1843 the young Karl Marx wrote in a critical essay on German philosophy that religion is “the opium of the people”, a phrase that would eventually harden into official atheism for the communist movement, though it poorly represented the true opinions of its founding theorist. After all, Marx also wrote that religion is “the sentiment of a heartless world” and “the soul of soul-less conditions”, as if to suggest that even the most fantastical beliefs bear within themselves a protest against worldly suffering and a promise to redeem us from conditions that might otherwise appear beyond all possible change. To call Marx a “secularist”, then, may be too simple. Marx saw religion as an illusion, but he was too much the dialectician to claim that it could be simply waved aside without granting that even illusions point darkly toward truth.

Marxism has had a long and troubled relationship with religion. In 1843 the young Karl Marx wrote in a critical essay on German philosophy that religion is “the opium of the people”, a phrase that would eventually harden into official atheism for the communist movement, though it poorly represented the true opinions of its founding theorist. After all, Marx also wrote that religion is “the sentiment of a heartless world” and “the soul of soul-less conditions”, as if to suggest that even the most fantastical beliefs bear within themselves a protest against worldly suffering and a promise to redeem us from conditions that might otherwise appear beyond all possible change. To call Marx a “secularist”, then, may be too simple. Marx saw religion as an illusion, but he was too much the dialectician to claim that it could be simply waved aside without granting that even illusions point darkly toward truth.

In the 20th century the story grew even more conflicted. While Soviet Marxism turned with a vengeance against religious believers and sought to dismantle religious institutions, some theorists in the West who saw in Marxism a resource for philosophical speculation felt that dialectics itself demanded a more nuanced understanding of religion, so that its energies could be harnessed for a task of redemption that was directed not to the heavens but to the Earth. Especially in Weimar Germany, Marxism and religion often came together into an explosive combination. Creative and heterodox thinkers such as Ernst Bloch fashioned speculative philosophies of history to show that the religious past contained untapped sources of messianic hope that kept alive the “spirit of utopia” for modern-day revolution. Anarchists such as Gustav Landauer, a leader of post-1918 socialist uprising who was murdered by the far-right in Bavaria, strayed from Marxism into an exotic syncretism of mystical and revolutionary thought.

More here.

Mass Delusion in America

Jeffrey Goldberg in The Atlantic:

Insurrection Day, 12:40 p.m.: A group of about 80 lumpen Trumpists were gathered outside the Commerce Department, near the White House. They organized themselves in a large circle, and stared at a boombox rigged to a megaphone. Their leader and, for some, savior—a number of them would profess to me their belief that the 45th president is an agent of God and his son, Jesus Christ—was rehearsing his pitiful list of grievances, and also fomenting a rebellion against, among others, the klatch of treacherous Republicans who had aligned themselves with the Constitution and against him. “A year from now we’re gonna start working on Congress,” Trump said through the boombox. “We gotta get rid of the weak congresspeople, the ones that aren’t any good, the Liz Cheneys of the world. We gotta get rid of them.” “Fuck Liz Cheney!” a man next to me yelled. He was bearded, and dressed in camouflage and Kevlar. His companion was dressed similarly, a valhalla: admit one patch sewn to his vest. Next to him was a woman wearing a full-body cat costume. “Fuck Liz Cheney!” she echoed. Catwoman, who would not tell me her name, carried a sign that read take off your mask smell the bullshit. Affixed to a corner of the sign was the letter Q.

Insurrection Day, 12:40 p.m.: A group of about 80 lumpen Trumpists were gathered outside the Commerce Department, near the White House. They organized themselves in a large circle, and stared at a boombox rigged to a megaphone. Their leader and, for some, savior—a number of them would profess to me their belief that the 45th president is an agent of God and his son, Jesus Christ—was rehearsing his pitiful list of grievances, and also fomenting a rebellion against, among others, the klatch of treacherous Republicans who had aligned themselves with the Constitution and against him. “A year from now we’re gonna start working on Congress,” Trump said through the boombox. “We gotta get rid of the weak congresspeople, the ones that aren’t any good, the Liz Cheneys of the world. We gotta get rid of them.” “Fuck Liz Cheney!” a man next to me yelled. He was bearded, and dressed in camouflage and Kevlar. His companion was dressed similarly, a valhalla: admit one patch sewn to his vest. Next to him was a woman wearing a full-body cat costume. “Fuck Liz Cheney!” she echoed. Catwoman, who would not tell me her name, carried a sign that read take off your mask smell the bullshit. Affixed to a corner of the sign was the letter Q.

“What’s your plan?” I asked her. People in the street, dozens at first, then hundreds, were moving past us, toward Pennsylvania Avenue, and then presumably on to the Capitol. “We’re going to stop the steal,” she answered. “If Pence isn’t going to stop it, we have to.” The treasonous behavior of Liz Cheney and many of her Republican colleagues was, to them, a fixed insurrectionary fact, but Pence was still in a plastic moment. Across the day, however, I could feel the Trump cult turning against him, as it turns against most everything.

More here.

Thursday Poem

Past is prologue —Anonymous

America

America I’ve given you all and now I’m nothing.

America two dollars and twentyseven cents January 17, 1956.

I can’t stand my own mind.

America when will we end the human war?

Go fuck yourself with your atom bomb.

I don’t feel good don’t bother me.

I won’t write my poem till I’m in my right mind.

America when will you be angelic?

When will you take off your clothes?

When will you look at yourself through the grave?

When will you be worthy of your million Trotskyites?

America why are your libraries full of tears?

America when will you send your eggs to India?

I’m sick of your insane demands.

When can I go into the supermarket and buy what I need with my good looks?

America after all it is you and I who are perfect not the next world.

Your machinery is too much for me.

You made me want to be a saint.

There must be some other way to settle this argument.

Burroughs is in Tangiers I don’t think he’ll come back it’s sinister.

Are you being sinister or is this some form of practical joke?

I’m trying to come to the point.

I refuse to give up my obsession.

America stop pushing I know what I’m doing.

America the plum blossoms are falling.

I haven’t read the newspapers for months, everyday somebody goes on trial for

…… murder.

America I feel sentimental about the Wobblies.

America I used to be a communist when I was a kid I’m not sorry.

I smoke marijuana every chance I get.

I sit in my house for days on end and stare at the roses in the closet.

When I go to Chinatown I get drunk and never get laid.

My mind is made up there’s going to be trouble.

You should have seen me reading Marx.

My psychoanalyst thinks I’m perfectly right.

I won’t say the Lord’s Prayer.

I have mystical visions and cosmic vibrations.

America I still haven’t told you what you did to Uncle Max after he came over from

…… Russia.

I’m addressing you.

Read more »

Slavoj Žižek – On G.W.F. Hegel

Colors / Tawny

Eileen Myles at Cabinet:

It’s interesting: there’s a wall along the freeway over there and there’s green dabs of paint every so often on it and a sun pouncing down. It feels kind of warm so the color isn’t right but there’s a feel. I’m thinking tawny isn’t a color. It’s a feeling. Like butter, the air in Hawaii, a feeling of value. Is anyone tawny who you can have. You know what I mean. It seems a slightly disdained object of lust. Her tawny skin—face it, used that way it’s a corrupt word. It isn’t even on the speaker. It’s on the spoken about. She or he is looking expensive and paid for. So I prefer to think about light. Open or closed. Closed is more literary light. Or light (there you go) of rooms you pass as you walk or drive by but most particularly I think as you ride by at night on a bike so you can smell the air out here and see the light in there, the light of a home you don’t know and feel mildly excited about, the light you’ll never know. Smokers with their backs to me standing in a sunset at the beach are closer to tawny than me.

It’s interesting: there’s a wall along the freeway over there and there’s green dabs of paint every so often on it and a sun pouncing down. It feels kind of warm so the color isn’t right but there’s a feel. I’m thinking tawny isn’t a color. It’s a feeling. Like butter, the air in Hawaii, a feeling of value. Is anyone tawny who you can have. You know what I mean. It seems a slightly disdained object of lust. Her tawny skin—face it, used that way it’s a corrupt word. It isn’t even on the speaker. It’s on the spoken about. She or he is looking expensive and paid for. So I prefer to think about light. Open or closed. Closed is more literary light. Or light (there you go) of rooms you pass as you walk or drive by but most particularly I think as you ride by at night on a bike so you can smell the air out here and see the light in there, the light of a home you don’t know and feel mildly excited about, the light you’ll never know. Smokers with their backs to me standing in a sunset at the beach are closer to tawny than me.

more here.

Too Nice to Be President

Tim Stanley at Literary Review:

This is the definitive Jimmy Carter anecdote. Once, when he was president, a bemused journalist asked if it was true that the leader of the free world was in charge of the schedule for the White House tennis court. Of course not, said Carter; don’t be silly. What he had done was tell staff they must speak to his secretary if they wanted to book a tennis session. That way, he elaborated, people cannot use the court simultaneously ‘unless they [are] either on opposite sides of the net or engaged in a doubles contest’.

This is the definitive Jimmy Carter anecdote. Once, when he was president, a bemused journalist asked if it was true that the leader of the free world was in charge of the schedule for the White House tennis court. Of course not, said Carter; don’t be silly. What he had done was tell staff they must speak to his secretary if they wanted to book a tennis session. That way, he elaborated, people cannot use the court simultaneously ‘unless they [are] either on opposite sides of the net or engaged in a doubles contest’.

Honest, wonky and utterly without humour, Carter was probably one of the smartest American presidents and, consequently, one of the worst. Two new accounts of his time in office bring clarity and depth to the record, albeit with varying degrees of sympathy.

more here.

Wednesday, January 6, 2021

No one with an interest in philosophy or debates about identity can afford to be ignorant of the work of Saul Kripke

Stephen Law in Aeon:

Born in 1940 in New York, Saul Kripke is one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century, yet few outside philosophy have heard of him, let alone have any familiarity with his ideas. Still, Kripke’s arguments are often fairly easy to grasp. And, as I explain here, his conclusions challenge widely held philosophical assumptions – including assumptions about the role and limits of philosophy itself.

Born in 1940 in New York, Saul Kripke is one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century, yet few outside philosophy have heard of him, let alone have any familiarity with his ideas. Still, Kripke’s arguments are often fairly easy to grasp. And, as I explain here, his conclusions challenge widely held philosophical assumptions – including assumptions about the role and limits of philosophy itself.

I’ll also provide one illustration of how Kripke’s ideas can have relevance outside philosophy – to heated political debates about identity, ‘biological essentialism’, and how terms such as ‘woman’ and ‘white person’ function (do such terms latch on to hidden genetic and/or other biological features, as some maintain?)

No one with an interest in philosophy, or in such debates, can afford to be entirely ignorant about what Kripke has to say.

More here.

Hate Working Out? Blame Evolution

Jen A. Miller in the New York Times:

On a recent Saturday morning, my dad and I walked our dogs to the local basketball court to see what a persistent “thump-thump” noise coming from that direction was all about. Instead of basketball players, we found a fitness “boot camp,” where a gaggle of people in bright, tight clothing did squats and lunges and burpees in different stations, all to the same beat.

On a recent Saturday morning, my dad and I walked our dogs to the local basketball court to see what a persistent “thump-thump” noise coming from that direction was all about. Instead of basketball players, we found a fitness “boot camp,” where a gaggle of people in bright, tight clothing did squats and lunges and burpees in different stations, all to the same beat.

“People are weird,” I said.

It’s not exactly that we’re weird, Daniel E. Lieberman argues in “Exercised: Why Something We Never Evolved to Do Is Healthy and Rewarding.” Instead, it’s the way we exercise that’s odd. “We never evolved to exercise,” Lieberman writes, and I suppose he would think that fitness boot camp was no weirder than my five-mile run earlier that morning, or my dad’s use of a Fitbit to track his steps. None of this is natural to human beings, and exercise is a constant game of trying to catch up to lives we were never really meant to lead.

Books about exercise are nothing new — especially not at this time of year. But “Exercised” is different from the usual scrum, in that its objective is not to sell a diet or fitness plan. Lieberman is a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University, and he comes to the material as a reluctant exerciser himself.

More here.

Joseph Stiglitz: How Biden Can Restore Multilateralism Unilaterally

Joseph E. Stiglitz in Project Syndicate:

The world needs more than Trump’s narrow transactional approach; so does the US. The only way forward is through true multilateralism, in which American exceptionalism is genuinely subordinated to common interests and values, international institutions, and a form of rule of law from which the US is not exempt. This would represent a major shift for the US, from a position of longstanding hegemony to one built on partnerships.

The world needs more than Trump’s narrow transactional approach; so does the US. The only way forward is through true multilateralism, in which American exceptionalism is genuinely subordinated to common interests and values, international institutions, and a form of rule of law from which the US is not exempt. This would represent a major shift for the US, from a position of longstanding hegemony to one built on partnerships.

Such an approach would not be unprecedented. After World War II, the US found that ceding some influence to international organizations like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund was actually in its own interests. The problem is that America didn’t go far enough. While John Maynard Keynes wisely called for the creation of a global currency – an idea later manifested in the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) – the US demanded veto power at the IMF, and didn’t vest the Fund with as much power as it should have.

More here.

Why Elton John takes 2½ minutes to get to the chorus in Tiny Dancer

Celan’s Poetry and the Politics of Language

Ryan Ruby at The Virginia Quarterly Review:

Celan’s gray language can be read as a subtle undermining of this principle of separation. Over the course of the four books collected in Memory Rose into Threshold Speech, there is a noticeable shift from a poetics of making-smooth to a poetics, as the color gray suggests, of entanglements, intertwinings, braids, weavings, mixtures. Although he once claimed that he did not believe in “bilingualism in poetry,” his poems have a distinctly international character, which is hardly surprising for a Romanian-born, German-speaking Jew working as a literary translator in Paris. (“International” was negatively connoted in the LTI and along with the adjective “global” it was frequently associated with Jews.) Many of his poems have foreign words as titles, or contain foreign words in them—French mostly, but also Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian—each of which can be read as a “shibboleth” “cry[ing] out” in the “homeland’s alienness” (“Shibboleth”). The borders between identities and languages do not always lie between individual people or individual words; sometimes they lie within them. In his poems, Celan stands inside himself and the German language, “naming on the thresholds / what enters and leaves” (“Together”).

Celan’s gray language can be read as a subtle undermining of this principle of separation. Over the course of the four books collected in Memory Rose into Threshold Speech, there is a noticeable shift from a poetics of making-smooth to a poetics, as the color gray suggests, of entanglements, intertwinings, braids, weavings, mixtures. Although he once claimed that he did not believe in “bilingualism in poetry,” his poems have a distinctly international character, which is hardly surprising for a Romanian-born, German-speaking Jew working as a literary translator in Paris. (“International” was negatively connoted in the LTI and along with the adjective “global” it was frequently associated with Jews.) Many of his poems have foreign words as titles, or contain foreign words in them—French mostly, but also Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian—each of which can be read as a “shibboleth” “cry[ing] out” in the “homeland’s alienness” (“Shibboleth”). The borders between identities and languages do not always lie between individual people or individual words; sometimes they lie within them. In his poems, Celan stands inside himself and the German language, “naming on the thresholds / what enters and leaves” (“Together”).

more here.

Bruno Latour – Inside the ‘Planetary Boundaries’: Gaia’s Estate

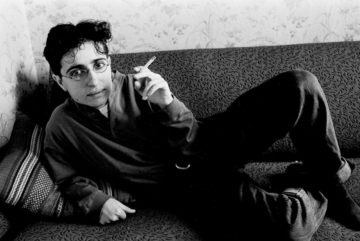

My Gender Is Masha Gessen

Jen Silverman at The Paris Review:

A friend of mine has departed from pronoun-related language to describe their own gender. “My gender is orange,” they said once. “My gender is chrome.” When I tried making my own list I was surprised by how quickly I knew the answers. My gender is denim, my gender is The Doubtful Guest, my gender is sunflower yellow. My gender is that photo of Masha Gessen lying on a couch, smoking languidly, giving you a look of intense expectation: Now what?

This image of Masha Gessen exists in stark contrast to the hopeless banality of the gender binary, because Masha Gessen has both repurposed and transcended that binary. Now they’re just getting on with being fabulous. In my imagined life of aspirational glamour, Masha is forever standing in front of floor-to-ceiling windows, giving you a look that says “… I wrote a book about totalitarianism?” whenever you want to ask silly questions about how they identify. Masha Gessen rocks a blazer like nobody else and has three kids and a partner whose facial symmetry is astonishing; they don’t have time to explain they/them pronouns.

more here.

Why 2021 could be turning point for tackling climate change

Justin Rowlatt in BBC News:

Covid-19 was the big issue of 2020, there is no question about that. But I’m hoping that, by the end of 2021, the vaccines will have kicked in and we’ll be talking more about climate than the coronavirus. 2021 will certainly be a crunch year for tackling climate change. Antonio Guterres, the UN Secretary General, told me he thinks it is a “make or break” moment for the issue. So, in the spirit of New Year’s optimism, here’s why I believe 2021 could confound the doomsters and see a breakthrough in global ambition on climate.

Covid-19 was the big issue of 2020, there is no question about that. But I’m hoping that, by the end of 2021, the vaccines will have kicked in and we’ll be talking more about climate than the coronavirus. 2021 will certainly be a crunch year for tackling climate change. Antonio Guterres, the UN Secretary General, told me he thinks it is a “make or break” moment for the issue. So, in the spirit of New Year’s optimism, here’s why I believe 2021 could confound the doomsters and see a breakthrough in global ambition on climate.

In November 2021, world leaders will be gathering in Glasgow for the successor to the landmark Paris meeting of 2015. Paris was important because it was the first time virtually all the nations of the world came together to agree they all needed to help tackle the issue. The problem was the commitments countries made to cutting carbon emissions back then fell way short of the targets set by the conference. In Paris, the world agreed to avoid the worst impacts of climate change by trying to limit global temperature increases to 2C above pre-industrial levels by the end of the century. The aim was to keep the rise to 1.5C if at all possible. We are way off track. On current plans the world is expected to breach the 1.5C ceiling within 12 years or less and to hit 3C of warming by the end of the century. Under the terms of the Paris deal, countries promised to come back every five years and raise their carbon-cutting ambitions. That was due to happen in Glasgow in November 2020. The pandemic put paid to that and the conference was bumped forward to this year. So, Glasgow 2021 gives us a forum at which those carbon cuts can be ratcheted up.

More here.

The Italian Novelist Who Envisioned a World Without Humanity

Alejandro Chacoff in The New Yorker:

In 1973, shortly after his last novel, like the others before it, was rejected by publishers, the Italian writer Guido Morselli shot himself in the head and died. He left several rejection letters on his desk, and a short note that read, “I bear no grudges.” It was the kind of gesture one of his protagonists might have performed—a show of ironic detachment that belied a deep and obvious pain. Morselli was sixty years old. Before returning to his family’s home in Varese and ending his life, he had been living in near-isolation for two decades, on a small property in Lombardy, near the Swiss-Italian border. There he tended to the land, made wine, and wrote books that faced diminishing odds of publication. The last one that he finished tells the story of an apocalyptic event in which all of humanity suddenly vanishes, leaving a single man as the world’s only witness.

In 1973, shortly after his last novel, like the others before it, was rejected by publishers, the Italian writer Guido Morselli shot himself in the head and died. He left several rejection letters on his desk, and a short note that read, “I bear no grudges.” It was the kind of gesture one of his protagonists might have performed—a show of ironic detachment that belied a deep and obvious pain. Morselli was sixty years old. Before returning to his family’s home in Varese and ending his life, he had been living in near-isolation for two decades, on a small property in Lombardy, near the Swiss-Italian border. There he tended to the land, made wine, and wrote books that faced diminishing odds of publication. The last one that he finished tells the story of an apocalyptic event in which all of humanity suddenly vanishes, leaving a single man as the world’s only witness.

That book, “Dissipatio H.G.” (NYRB Classics), has now been published in English, in a translation by Frederika Randall, a journalist who turned to translating Italian after experiencing health problems caused by a fall. The plot begins with a botched suicide attempt: the unnamed narrator, a loner living in a retreat surrounded by meadows and glaciers, walks to a cave, on the eve of his fortieth birthday, intent on throwing himself down a well that leads to an underground lake. “Because the negative outweighed the positive,” he explains. “On my scales. By seventy percent. Was that a banal motive? I’m not sure.”

Sitting on the edge of the well, he doesn’t so much lose heart as get distracted. The mood is all wrong; he feels calm, lucid, too upbeat to go through with it. He is carrying a flashlight, which he flicks on and off. “Feet dangling in the dark,” he takes a sip of the brandy he has brought with him and considers how the Spanish variety is better than the French and why this is so widely unappreciated. Before leaving the cave, he bumps his head on a rock, and hears a peal of thunder: it’s the season’s first storm. Back home, lying in bed and still dressed, annoyed at the last-minute change of plans, he picks up a gun, considering an easier solution. He brings the “black-eyed girl” to his mouth and pulls the trigger, twice. The gun doesn’t work. He falls asleep.

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Revisions

Before the poet was a poet

nothing was reworked:

not the smudge of ink on twelve sets of clothes

not the fearsome top berth on the train

not a room full of boxes and dull windows

not the cat that left its kittens and afterbirth in a pair of jeans

not doubt.

Before the poet was a poet

everything had a place:

six years were six years parallel lines followed rules

like obedient children

[the Dewey Decimal System]

………………………………………………….. homes remained where they’d

been left.

Before the poet was a poet

many things went unseen:

clouds sometimes wheedled a ray out of the sun| parents kept photos under their

pillows| letters never said everything they wanted to| lectures were interrupted by a

commotion of leaves | | every step was upon a blind spot.

by Sridala Swami

from Escape Artist

Aleph Book Co., New Delhi, 2014

Tuesday, January 5, 2021

The Minds Of Kant, Dennett And Freud

Richard Marshall interviews Andrew Brook at 3:16:

3:16: You’ve worked a deal in philosophical issues arising in the various areas of cognitive science. Starting there then, so we get a sense of the landscape, what is the philosopher’s role in this area? Some non-philosophers (and a few philosophers) would wonder whether there’s any point to heeding philosophers here – the thought is that the scientists have it all locked down and under control! So what’s the difference between philosophy in cognitive science and philosophy of cognitive science and what are philosophers doing in the former?

AB: Yes, indeed! I was there when Christof Koch, a cognitive neuroscientist of international renown, said that philosophers had made a good speculative start but scientists (he meant ‘we scientists’) are now doing the job properly. A view that betrays a deep-running ignorance of philosophy, in my opinion. Philosophy has a central role to play in cognitive science and philosophy of cognitive science still has a lot of work to do. In cognitive science, philosophers do vital work clarifying concepts (the conceptual toolbox of cognitive research is a mess) and showing how hypotheses and theories relate to one another – in short, showing how things, in the broadest sense of ‘things’, hang together, in the broadest sense of ‘hang together’, as the outstanding American philosopher Wilfred Sellars put it some decades ago. Philosophy of cognitive science is just a branch of philosophy of science, though the wide range of styles of explanation used by cognitive researchers, just to take one example, offer some special challenges.

AB: Yes, indeed! I was there when Christof Koch, a cognitive neuroscientist of international renown, said that philosophers had made a good speculative start but scientists (he meant ‘we scientists’) are now doing the job properly. A view that betrays a deep-running ignorance of philosophy, in my opinion. Philosophy has a central role to play in cognitive science and philosophy of cognitive science still has a lot of work to do. In cognitive science, philosophers do vital work clarifying concepts (the conceptual toolbox of cognitive research is a mess) and showing how hypotheses and theories relate to one another – in short, showing how things, in the broadest sense of ‘things’, hang together, in the broadest sense of ‘hang together’, as the outstanding American philosopher Wilfred Sellars put it some decades ago. Philosophy of cognitive science is just a branch of philosophy of science, though the wide range of styles of explanation used by cognitive researchers, just to take one example, offer some special challenges.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Joe Henrich on the WEIRDness of the West

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

We all know stereotypes about people from different countries; but we also recognize that there really are broad cultural differences between people who grow up in different societies. This raises a challenge when most psychological research is performed on a narrow and unrepresentative slice of the world’s population — a subset that has accurately been labeled as WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic). Joseph Henrich has argued that focusing on this group has led to systematic biases in how we think about human psychology. In his new book, he proposes a surprising theory for how WEIRD people got that way, based on the Church insisting on the elimination of marriage to relatives. It’s an audacious idea that nudges us to rethink how the WEIRD world came to be.

We all know stereotypes about people from different countries; but we also recognize that there really are broad cultural differences between people who grow up in different societies. This raises a challenge when most psychological research is performed on a narrow and unrepresentative slice of the world’s population — a subset that has accurately been labeled as WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic). Joseph Henrich has argued that focusing on this group has led to systematic biases in how we think about human psychology. In his new book, he proposes a surprising theory for how WEIRD people got that way, based on the Church insisting on the elimination of marriage to relatives. It’s an audacious idea that nudges us to rethink how the WEIRD world came to be.

More here.

Yanis Varoufakis: The Seven Secrets of 2020

Yanis Varoufakis at Project Syndicate:

We used to think, with good reason, that globalization had defanged national governments. Presidents cowered before the bond markets. Prime ministers ignored their country’s poor but never Standard & Poor’s. Finance ministers behaved like Goldman Sachs’s knaves and the International Monetary Fund’s satraps. Media moguls, oil men, and financiers, no less than left-wing critics of globalized capitalism, agreed that governments were no longer in control.

We used to think, with good reason, that globalization had defanged national governments. Presidents cowered before the bond markets. Prime ministers ignored their country’s poor but never Standard & Poor’s. Finance ministers behaved like Goldman Sachs’s knaves and the International Monetary Fund’s satraps. Media moguls, oil men, and financiers, no less than left-wing critics of globalized capitalism, agreed that governments were no longer in control.

Then the pandemic struck. Overnight, governments grew claws and bared sharpened teeth. They closed borders and grounded planes, imposed draconian curfews on our cities, shut down our theatres and museums, and forbade us from comforting our dying parents. They even did what no one thought possible before the Apocalypse: they canceled sporting events.

The first secret was thus exposed: Governments retain inexorable power. What we discovered in 2020 is that governments had been choosing not to exercise their enormous powers so that those whom globalization had enriched could exercise their own.

The second truth is one that many people suspected but were too timid to call out: the money-tree is real. Governments that proclaimed their impecunity whenever called upon to pay for a hospital here or a school there suddenly discovered oodles of cash to pay for furlough wages, nationalize railways, take over airlines, support carmakers, and even prop up gyms and hairdressers.

More here.