Category: Recommended Reading

Living Like Cats

Kevin Power at the Dublin Review of Books:

But let’s say it again: to call Gray a misanthrope or a reactionary or a nationalist (or to apply to him any other term from the vocabulary of contemporary political morality) is to miss the point. His books are not attacks on humanity as such. Nor is he tubthumping for a particular politics or even a particular morality (I’ll come in a moment to the question of whether or not a specific politics can or should be extracted from Gray’s work). Instead, his books are in the first instance the record of an honourable attempt to discover what can be said about human beings if we dispense, as thoroughly as we can, with the things that human beings have said about themselves. To step out of Gray’s Total Perspective Vortex and ask, “But what’s left?” is to misunderstand the purpose of the Vortex. What’s left, when Gray is finished, is everything: life, death, nature, the universe. All there is, in other words. The point is the seeing. In the final sentence of Straw Dogs, he asks, “Can we not think of the aim of life as being simply to see?”

But let’s say it again: to call Gray a misanthrope or a reactionary or a nationalist (or to apply to him any other term from the vocabulary of contemporary political morality) is to miss the point. His books are not attacks on humanity as such. Nor is he tubthumping for a particular politics or even a particular morality (I’ll come in a moment to the question of whether or not a specific politics can or should be extracted from Gray’s work). Instead, his books are in the first instance the record of an honourable attempt to discover what can be said about human beings if we dispense, as thoroughly as we can, with the things that human beings have said about themselves. To step out of Gray’s Total Perspective Vortex and ask, “But what’s left?” is to misunderstand the purpose of the Vortex. What’s left, when Gray is finished, is everything: life, death, nature, the universe. All there is, in other words. The point is the seeing. In the final sentence of Straw Dogs, he asks, “Can we not think of the aim of life as being simply to see?”

more here.

On Heinrich von Kleist

David Wellbery at Nonsite:

The brief examination of the work of Heinrich von Kleist (1777-1811) conducted here is intended as an essay in criticism in the spirit of Sartre: “Une technique romanesque renvoie toujours à la métaphysique du romancier. La tâche du critique est de dégager celle-ci avant d’apprécier celle-là.” The concept of metaphysics Sartre employs refers, on my reading, to the hardly controversial thought that literary works generally (not only novels) render worlds imaginatively present, and that these worlds exhibit principles of intelligibility. To free up the metaphysics of an artistic world, then, is to solicit the deep criteria (or categories) that organize that world. Such criticism brings the form of an aesthetically achieved world to light and demonstrates how that form is made salient linguistically, rhetorically, narratively, dramatically, and so forth. Call this the non-formalistic criticism of form. Needless to say, the account of Kleist’s work I develop here does not aspire to exhaustiveness. The aim, rather, is to limn the contours of Kleist’s artistic achievement such that acknowledgement of its originality and importance is felt to constitute an intellectual obligation. Acknowledgement, a variant of Hegelian “recognition,” deserves to replace the now faded and, in Sartre’s use, merely technical notion of appreciation.

The brief examination of the work of Heinrich von Kleist (1777-1811) conducted here is intended as an essay in criticism in the spirit of Sartre: “Une technique romanesque renvoie toujours à la métaphysique du romancier. La tâche du critique est de dégager celle-ci avant d’apprécier celle-là.” The concept of metaphysics Sartre employs refers, on my reading, to the hardly controversial thought that literary works generally (not only novels) render worlds imaginatively present, and that these worlds exhibit principles of intelligibility. To free up the metaphysics of an artistic world, then, is to solicit the deep criteria (or categories) that organize that world. Such criticism brings the form of an aesthetically achieved world to light and demonstrates how that form is made salient linguistically, rhetorically, narratively, dramatically, and so forth. Call this the non-formalistic criticism of form. Needless to say, the account of Kleist’s work I develop here does not aspire to exhaustiveness. The aim, rather, is to limn the contours of Kleist’s artistic achievement such that acknowledgement of its originality and importance is felt to constitute an intellectual obligation. Acknowledgement, a variant of Hegelian “recognition,” deserves to replace the now faded and, in Sartre’s use, merely technical notion of appreciation.

more here.

Thursday Poem

How to Measure Distance

1.Only Use Light Years When Talking to the General Public

or to squirrels who test spring between two

branches. Or to a new mother saddened

by thoughts of earth and its death; sun’s death;

her death. She watches her husband leave

the room for a burp cloth, wonders, could she

do it without him? What’s the measurement

of distance between two people growing

too close, too quickly?

2. The Measures We Use Depend on What We Are Measuring

Distance between parents? Hills? Rogue comets?

Within our solar system, distance is

measured in Astronomical Units.

Or “A.U.,” an abbreviation that

sounds similar to the “ow” of a toe

stub. Or similar to the sound of a mother

teaching the beginning of all sound. “Ah,

eh, ee, oo, uu.” Watch her mouth widen,

purr, and close. This is the measurement

for what we call breath.

DNA hard drives? Scientists hide a coded digital message in bacterial DNA

Matthew Rozsa in Salon:

Visualize, if you will, a group of bacteria cells. They are kind of silly looking, when you get right down to it: shaped like a sphere or a pill, sometimes covered in tiny hairs or spikes. While technically alive, it is hard to imagine them as being particularly intelligent, much less capable of storing information like artificially intelligent machines such as computers. Curiously, that’s exactly what a group of researchers just did: edited DNA inside individual bacteria cells in order to store digital data.

Visualize, if you will, a group of bacteria cells. They are kind of silly looking, when you get right down to it: shaped like a sphere or a pill, sometimes covered in tiny hairs or spikes. While technically alive, it is hard to imagine them as being particularly intelligent, much less capable of storing information like artificially intelligent machines such as computers. Curiously, that’s exactly what a group of researchers just did: edited DNA inside individual bacteria cells in order to store digital data.

A new paper by researchers at Columbia University reveals that they were able to modify the DNA of bacteria cells by inserting specific DNA sequences with encoded data that could be translated into the message “Hello world!” Specifically the DNA sequences were modified to represent the 0s and 1s used in binary code (the same code that is used in computers) and then assembled in various arrangements to correspond with letters of the English alphabet. The end result is that the words “hello” and “world” were written and encoded into the DNA of E. coli cells.

Just as the English alphabet has twenty-six letters that comprise it, DNA has four compounds that serve as the basis for the genetic code: adenine, cytosine, guanine and thymine. These building blocks that comprise DNA molecules can be modified to store “bits” of information. Two of the Columbia University scientists behind the new research — Ross McBee, a PhD candidate, and Sung Sun Yim, a postdoctoral fellow — explained to Salon by email that they modified the bacterial DNA code using a technology known as CRISPR/Cas9 genetic scissors (or CRISPR for short), which allows scientists to directly alter DNA. (The scientists who developed CRISPR technology won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry last year for their invention.)

More here.

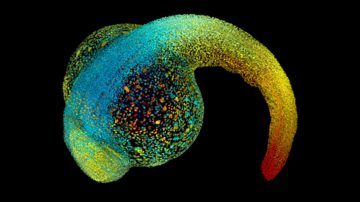

The secret forces that squeeze and pull life into shape

Amber Dance in Nature:

At first, an embryo has no front or back, head or tail. It’s a simple sphere of cells. But soon enough, the smooth clump begins to change. Fluid pools in the middle of the sphere. Cells flow like honey to take up their positions in the future body. Sheets of cells fold origami-style, building a heart, a gut, a brain. None of this could happen without forces that squeeze, bend and tug the growing animal into shape. Even when it reaches adulthood, its cells will continue to respond to pushing and pulling — by each other and from the environment. Yet the manner in which bodies and tissues take form remains “one of the most important, and still poorly understood, questions of our time”, says developmental biologist Amy Shyer, who studies morphogenesis at the Rockefeller University in New York City. For decades, biologists have focused on the ways in which genes and other biomolecules shape bodies, mainly because the tools to analyse these signals are readily available and always improving. Mechanical forces have received much less attention.

At first, an embryo has no front or back, head or tail. It’s a simple sphere of cells. But soon enough, the smooth clump begins to change. Fluid pools in the middle of the sphere. Cells flow like honey to take up their positions in the future body. Sheets of cells fold origami-style, building a heart, a gut, a brain. None of this could happen without forces that squeeze, bend and tug the growing animal into shape. Even when it reaches adulthood, its cells will continue to respond to pushing and pulling — by each other and from the environment. Yet the manner in which bodies and tissues take form remains “one of the most important, and still poorly understood, questions of our time”, says developmental biologist Amy Shyer, who studies morphogenesis at the Rockefeller University in New York City. For decades, biologists have focused on the ways in which genes and other biomolecules shape bodies, mainly because the tools to analyse these signals are readily available and always improving. Mechanical forces have received much less attention.

But considering only genes and biomolecules is “like you’re trying to write a book with only half the letters of the alphabet”, says Xavier Trepat, a mechanobiologist at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia in Barcelona, Spain.

More here.

Wednesday, January 13, 2021

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, Towering Figure in Urdu Literature, Dies of COVID at 85

Shalini Venugopal Bhagat in the New York Times:

Mr. Faruqi has been credited among scholars with the revival of Urdu literature, especially from the 18th and 19th centuries. His output as a scholar, editor, publisher, critic, literary historian, translator and acclaimed writer of both poetry and novels was varied and prolific.

Mr. Faruqi has been credited among scholars with the revival of Urdu literature, especially from the 18th and 19th centuries. His output as a scholar, editor, publisher, critic, literary historian, translator and acclaimed writer of both poetry and novels was varied and prolific.

His primary focus was on retrieving Indo-Islamic culture and literature from the effects of colonialism. The left-wing Progressive Writers’ Movement had been in vogue since the 1930s, when India was still under British rule. Literature that did not conform to its Marxist ideals of revolution had fallen out of favor. In 1966, when Mr. Faruqi became the founding editor and publisher of the modernist literary journal Shabkhoon, he provided a platform for other voices and mentored many young writers to write what they wanted, in the style they wanted.

In addition to commissioning all the writing in the magazine, he edited every piece and wrote poetry, criticism and Urdu translations of important works. He did this work in addition to his job as a civil servant with the Indian Postal Service.

More here.

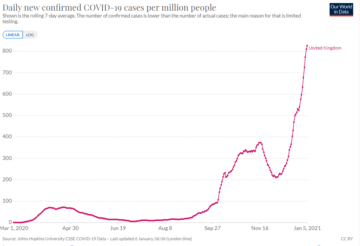

The New COVID Strain: How Bad Is It?

Brendan Foht and Ari Schulman in The New Atlantis:

Let’s start with the good news.

Let’s start with the good news.

It appears that the new strain of SARS-CoV-2, which scientists call B.1.1.7 (but we will just call it “new Covid”) causes the same illness as the already known strains of the virus (which we will collectively call “old Covid”). New Covid is a respiratory illness with seemingly the same symptoms as old Covid. And from what we know so far, if you get it your odds of becoming severely ill or dying are probably not dramatically different than with old Covid. So we’re still not facing a Contagion scenario.

Now the bad news. New Covid spreads much more aggressively. That could mean the return of runaway spread like we saw in March. And it could mean that reaching herd immunity will require a larger share of people to be infected or vaccinated. So we may be looking at a deadlier and longer pandemic unless smart, aggressive action is taken right now.

More here.

Garry Kasparov: What happens next

Garry Kasparov at CNN:

History teaches us the cost of well-meaning but shortsighted attempts to sacrifice justice for unity. Russians learned this in the hardest possible way after the fall of the Soviet Union. As I discussed at length in my book, Winter Is Coming, they declined to root out the KGB security state in the interest of national harmony. It would be too traumatic, our leaders said, to expose the countless atrocities the Soviet security forces committed and to punish their authors.

A feeble truth commission was quickly abandoned by President Boris Yeltsin, and soon even the Soviet archives were closed, although not before researchers like Vladimir Bukovsky revealed some of the KGB’s atrocities. The KGB’s name was changed to the FSB and its members quietly stayed in touch and intact. The result? A mere nine years after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Russia elected a former KGB lieutenant colonel, Vladimir Putin, to the presidency. It was the last meaningful election we ever had. We chose unity and we got dictatorship.

America should not make a similar mistake.

More here.

Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Message Following the Attack on the Capitol

Keith Haring Documentary

An Interview with Alphonso Lingis

Jeremy Butman and Alphonso Lingis at The Believer:

THE BELIEVER: Your books combine elements of memoir, epistemological analysis, ontological meditation, anthropological observation, and plenty of other genres. They are usually written in the first person (singular or plural), and sometimes in the second person. How did you decide to adopt this freedom of style, and what do you hope to accomplish with it?

THE BELIEVER: Your books combine elements of memoir, epistemological analysis, ontological meditation, anthropological observation, and plenty of other genres. They are usually written in the first person (singular or plural), and sometimes in the second person. How did you decide to adopt this freedom of style, and what do you hope to accomplish with it?

ALPHONSO LINGIS: Our thought arises in so many different events and [on so many] levels, and our discourse offers so many ways to formulate and communicate an insight. Ideally, the encounter and insight one seeks to share should induce the appropriate vocabulary, rhetoric, and explanation by means of narrative, exposition, or argument. I do not reflect about these and determine them separately. Often several versions are worked on until the right one becomes clear. It is important to me not to reflect much on why and how a given essay worked; it is important that it not become a template for subsequent essays. Hopefully the topic of the next essay will induce the right way to write to share the insight.

more here.

On Jean Valentine

Hafizah Geter at The Paris Review:

She was a poet who could carve both stillness and speed from the gap and one who, for me, lit the match. She was the poet who first taught me to obsess over the responsibility of the line break and in her house, she held her shoulders like a woman no longer afraid to let it be known she liked to be amused. Whatever she and her line breaks had been through, she’d long ago found the courage to say.

She was a poet who could carve both stillness and speed from the gap and one who, for me, lit the match. She was the poet who first taught me to obsess over the responsibility of the line break and in her house, she held her shoulders like a woman no longer afraid to let it be known she liked to be amused. Whatever she and her line breaks had been through, she’d long ago found the courage to say.

People are not wanting /—“How much breath,” she asked me in her living room, “do you need to get where you want to go?”—to let me in.

For years of my adolescence, it was like the Counting Crows’ “Long December” was always on. I had a loneliness in me so big, yet so compact, it could have been shaped like a Jean Valentine poem.

more here.

Wednesday Poem

Sailing to Byzantium

That is no country for old men. The young

In one another’s arms, birds in the trees

—Those dying generations—at their song,

The salmon-falls, the mackerel-crowded seas,

Fish, flesh, or fowl, commend all summer long

Whatever is begotten, born, and dies.

Caught in that sensual music all neglect

Monuments of unageing intellect.

An aged man is but a paltry thing,

A tattered coat upon a stick, unless

Soul clap its hands and sing, and louder sing

For every tatter in its mortal dress,

Nor is there singing school but studying

Monuments of its own magnificence;

And therefore I have sailed the seas and come

To the holy city of Byzantium.

O sages standing in God’s holy fire

As in the gold mosaic of a wall,

Come from the holy fire, perne in a gyre,

And be the singing-masters of my soul.

Consume my heart away; sick with desire

And fastened to a dying animal

It knows not what it is; and gather me

Into the artifice of eternity.

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing,

But such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make

Of hammered gold and gold enameling

To keep a drowsy Emperor awake;

Or set upon a golden bough to sing

To lords and ladies of Byzantium

Of what is past, or passing, or to come.

by William Butler Yeats

________________

*perne: spin

The ‘Shared Psychosis’ of Donald Trump and His Loyalists

Tanya Lewis in Scientific American:

The violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol Building last week, incited by President Donald Trump, serves as the grimmest moment in one of the darkest chapters in the nation’s history. Yet the rioters’ actions—and Trump’s own role in, and response to, them—come as little surprise to many, particularly those who have been studying the president’s mental fitness and the psychology of his most ardent followers since he took office. One such person is Bandy X. Lee, a forensic psychiatrist and president of the World Mental Health Coalition.

The violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol Building last week, incited by President Donald Trump, serves as the grimmest moment in one of the darkest chapters in the nation’s history. Yet the rioters’ actions—and Trump’s own role in, and response to, them—come as little surprise to many, particularly those who have been studying the president’s mental fitness and the psychology of his most ardent followers since he took office. One such person is Bandy X. Lee, a forensic psychiatrist and president of the World Mental Health Coalition.

…What attracts people to Trump? What is their animus or driving force?

The reasons are multiple and varied, but in my recent public-service book, Profile of a Nation, I have outlined two major emotional drives: narcissistic symbiosis and shared psychosis. Narcissistic symbiosis refers to the developmental wounds that make the leader-follower relationship magnetically attractive. The leader, hungry for adulation to compensate for an inner lack of self-worth, projects grandiose omnipotence—while the followers, rendered needy by societal stress or developmental injury, yearn for a parental figure. When such wounded individuals are given positions of power, they arouse similar pathology in the population that creates a “lock and key” relationship.

“Shared psychosis”—which is also called “folie à millions” [“madness for millions”] when occurring at the national level or “induced delusions”—refers to the infectiousness of severe symptoms that goes beyond ordinary group psychology. When a highly symptomatic individual is placed in an influential position, the person’s symptoms can spread through the population through emotional bonds, heightening existing pathologies and inducing delusions, paranoia and propensity for violence—even in previously healthy individuals. The treatment is removal of exposure.

More here.

The Bitter Fruits of Trump’s White-Power Presidency

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor in The New Yorker:

The spectacular violence in the Capitol on January 6th was the outcome of Donald Trump’s yearslong dalliance with the white-supremacist right. Trump all but promised an attack of some kind as he called for his followers to descend on Washington, D.C., for a “wild” protest to stop the certification of Joe Biden’s Electoral College victory. In a speech inciting his supporters to lay siege to the Capitol, he told them, “We will never give up. We will never concede.” He encouraged them to “fight like hell,” saying that otherwise they would lose their country, and dispatched them to the Capitol. He promised that he would be with them. But, like a lazy coward, Trump went home to watch the show on TV.

The spectacular violence in the Capitol on January 6th was the outcome of Donald Trump’s yearslong dalliance with the white-supremacist right. Trump all but promised an attack of some kind as he called for his followers to descend on Washington, D.C., for a “wild” protest to stop the certification of Joe Biden’s Electoral College victory. In a speech inciting his supporters to lay siege to the Capitol, he told them, “We will never give up. We will never concede.” He encouraged them to “fight like hell,” saying that otherwise they would lose their country, and dispatched them to the Capitol. He promised that he would be with them. But, like a lazy coward, Trump went home to watch the show on TV.

The white right-wing assault on the Capitol, with a Confederate flag in the building and gallows on the lawn, was alarming yet wholly predictable as Trump’s frantic efforts to hold on to power faltered. Not only did Trump clearly incite violence with his speech, but his Administration also paved the way for the violence through its deliberate neglect of the rising threat of white extremism. The Center for Strategic and International Studies found that attacks by far-right perpetrators more than quadrupled between 2016 and 2017. Yet even as the threat of white-supremacist violence grew, it commanded little interest or acknowledgment from the Trump Administration. The Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Targeted Violence and Terrorism Prevention, which was restructured and renamed in 2019, is dedicated to investigating extremism and domestic terrorism. Between 2017 and 2019, its operating budget was cut from twenty-one million dollars to less than three million, and the number of its full-time employees dwindled from forty to fewer than ten.

Instead of investigating white supremacists, the Trump Administration has surveilled the Black Lives Matter movement and other minority activists.

More here.

Tuesday, January 12, 2021

An Exceptional Situation: January 6 and the New State of Suspension

Justin E. H. Smith in his Substack Newsletter:

Often it seems a shame that those in opposing camps do not take time to stop and appreciate what they have in common: their certainty.

Often it seems a shame that those in opposing camps do not take time to stop and appreciate what they have in common: their certainty.

This shame has been particularly evident since January 6, in the work of all the hermeneuticists newly dedicated to interpreting that day’s events and what they portend for our republic. Was it a gruesome death-throe of Trumpism, or was it just the beginning of our own anni di piombo? Was it a proper fascist insurgency, or mostly just larping? Now that it has happened —whatever it was— should Trump be impeached for a second time, and Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley punished and ostracized, or should the Democrats focus, as Biden seems to want to do, on other pressing matters and let bygones be bygones for the sake of national unity? Are Trump’s suspension from social media and Parler’s disappearance from big-tech platforms justified, or is it an unacceptable state of affairs in which private media companies make largely arbitrary and inconsistent decisions as to who can be heard, rendering themselves in effect more powerful than democratically chosen leaders?

More here.

Sean Carroll: Democracy in America

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

The first full week of 2021 has been action-packed for those of us in the United States of America, for reasons you’re probably aware of, including a riotous mob storming the US Capitol. The situation has spurred me to take the unusual step of doing a solo podcast in response to current events. But never fear, I’m not actually trying to analyze current events for their own sakes. Rather, I’m using them as a jumping-off point for a more general discussion of how democracy is supposed to work and how we can make it better. We’ve talked about related topics recently with Cornel West and David Stasavage, but there are things I wanted to say in my own voice that fit well here. Politics is important everywhere, and it’s a crucial responsibility for those of us who live in societies that aspire to be participatory and democratic. We have to think these things through, and that’s what this podcast is all about.

The first full week of 2021 has been action-packed for those of us in the United States of America, for reasons you’re probably aware of, including a riotous mob storming the US Capitol. The situation has spurred me to take the unusual step of doing a solo podcast in response to current events. But never fear, I’m not actually trying to analyze current events for their own sakes. Rather, I’m using them as a jumping-off point for a more general discussion of how democracy is supposed to work and how we can make it better. We’ve talked about related topics recently with Cornel West and David Stasavage, but there are things I wanted to say in my own voice that fit well here. Politics is important everywhere, and it’s a crucial responsibility for those of us who live in societies that aspire to be participatory and democratic. We have to think these things through, and that’s what this podcast is all about.

More here.

Brain-Bending 3D Schröder Staircase Optical Illusion Won Best Illusion of The Year 2020 Contest

More details here.

How Will Biden Intervene?

Joseph S. Nye, Jr. in Project Syndicate:

American foreign policy tends to oscillate between inward and outward orientations. President George W. Bush was an interventionist; his successor, Barack Obama, less so. And Donald Trump was mostly non-interventionist. What should we expect from Joe Biden?

American foreign policy tends to oscillate between inward and outward orientations. President George W. Bush was an interventionist; his successor, Barack Obama, less so. And Donald Trump was mostly non-interventionist. What should we expect from Joe Biden?

In 1821, John Quincy Adams famously stated that the United States “does not go abroad in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.” But America also has a long interventionist tradition. Even a self-proclaimed realist like Teddy Roosevelt argued that in extreme cases of abuse of human rights, intervention “may be justifiable and proper.” John F. Kennedy called for Americans to ask not only what they could do for their country, but for the world.

Since the Cold War’s end, the US has been involved in seven wars and military interventions, none directly related to great power competition. George W. Bush’s 2006 National Security Strategy proclaimed a goal of freedom embodied in a global community of democracies.

More here.