Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite interviews Katrina Forrester over at Renewal:

Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite interviews Katrina Forrester over at Renewal:

Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite (FSB): The first part of your book, In the Shadow of Justice (Princeton 2019), goes back to the 1950s, when the basic parameters of Rawls’s theory of justice were, you argue, set. As a historian of Britain, I was fascinated by how much the British Labour Party’s revisionists shaped Rawls in the 1950s – you suggest, in fact, that his theory brought ‘philosophical order to the ideas of the Labour revisionists’ (p25). But because it was so fundamentally formed in this period, Rawlsianism was premised on continuing high levels of growth and public buy-in for welfare programmes, two things that Labour revisionists took for granted but which would become much less secure in the years after the publication of A Theory of Justice in 1971. In the following decades, as you show, a cohort of Rawlsian political philosophers, defending his work from attacks on left and right, firmed up and elaborated Rawls’s already immensely ambitious theory into a kind of juggernaut: huge, with a vast, rigid structure, very slow to turn around, but immensely powerful. Rawlsianism didn’t just come to dominate liberal political philosophy, it essentially defined liberal egalitarianism. Other philosophers had to work in its shadow. You want, in your book, to ‘denaturalize and defamiliarize’ the canons of liberal egalitarianism (p275). What’s the practical payoff from doing this?

Katrina Forrester (KF): It can be hard to see the assumptions that underpin a particular way of thinking, and to see the different choices that go into making up the conceptual frameworks that we take for granted and that are coded as ‘intuitive’. Among political philosophers, liberal egalitarianism has been a dominant way of thinking about politics, society and ethics, for decades. Though its origins in the political philosophy of John Rawls are constantly revisited, sometimes in a quasi-scriptural way, its political origins are less often interrogated. I wanted to ask what we see if we take liberal egalitarianism as a historical phenomenon to be explained. If it is recast as one of the twentieth century’s languages of liberalism, a framework that is one among many, then we might be better placed to ask if it’s a language and a framework we want to use.

More here.

Houman Barekat in LA Review of Books:

Houman Barekat in LA Review of Books: Mike Konczal in Boston Review:

Mike Konczal in Boston Review: Like school, work conferences and visiting your grandparents, this year’s

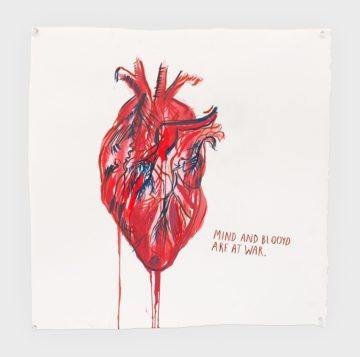

Like school, work conferences and visiting your grandparents, this year’s  Even if, especially if, Trump leaves—and some portion of us are lulled into mistaking his ascendency for an aberration—we’ll have to choose to look at hate, even as the press swells with self-congratulatory stories of a nation rejecting “division.” Because the hate of which Trump is the coalescence, the coagulation, was not an aberration, it was an inevitability.

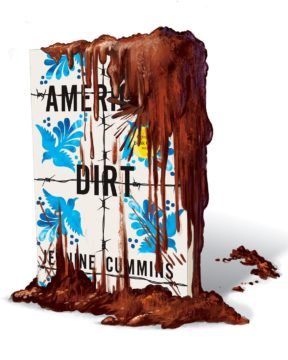

Even if, especially if, Trump leaves—and some portion of us are lulled into mistaking his ascendency for an aberration—we’ll have to choose to look at hate, even as the press swells with self-congratulatory stories of a nation rejecting “division.” Because the hate of which Trump is the coalescence, the coagulation, was not an aberration, it was an inevitability. On a mild Monday this past February, a tense meeting unfolded in a skyscraper in downtown Manhattan. Four Latinx writers and activists sat on one side of a long conference table. Facing them was a collection of white editors and executives from Macmillan, the publishing house that had recently put out

On a mild Monday this past February, a tense meeting unfolded in a skyscraper in downtown Manhattan. Four Latinx writers and activists sat on one side of a long conference table. Facing them was a collection of white editors and executives from Macmillan, the publishing house that had recently put out

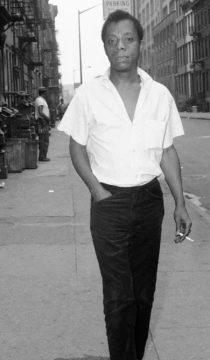

Michael Ondaatje once wrote that if Van Gogh was “our 19th-century artist-saint” then James Baldwin was “our 20th-century one”. For many, Baldwin’s writing has long been a touchstone of anti-racist humanism, but the sense of that particular epithet has never landed more emphatically for me than while reading Eddie S Glaude Jr’s Begin Again, his potent meditation on the enduring legacy of Baldwin’s life and thought, a New York Times bestseller and one of a number of titles that have spoken to the soul of public outrage at

Michael Ondaatje once wrote that if Van Gogh was “our 19th-century artist-saint” then James Baldwin was “our 20th-century one”. For many, Baldwin’s writing has long been a touchstone of anti-racist humanism, but the sense of that particular epithet has never landed more emphatically for me than while reading Eddie S Glaude Jr’s Begin Again, his potent meditation on the enduring legacy of Baldwin’s life and thought, a New York Times bestseller and one of a number of titles that have spoken to the soul of public outrage at  An old man with a shaggy white beard and matching hair stands in front of an audience of seekers and flower children. They are looking for ways of amplifying their human potential, of becoming more aware of their sense perceptions. It’s the tail end of the 1960s and the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, is where it’s happening.

An old man with a shaggy white beard and matching hair stands in front of an audience of seekers and flower children. They are looking for ways of amplifying their human potential, of becoming more aware of their sense perceptions. It’s the tail end of the 1960s and the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, is where it’s happening.  On Jan. 1, 2021, five long years after the vote for what’s become known as

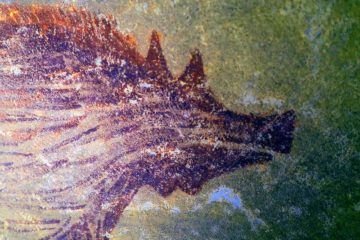

On Jan. 1, 2021, five long years after the vote for what’s become known as  Archaeologists believe they have discovered the world’s oldest-known representational artwork: three wild pigs painted deep in a limestone cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi at least 45,500 years ago.

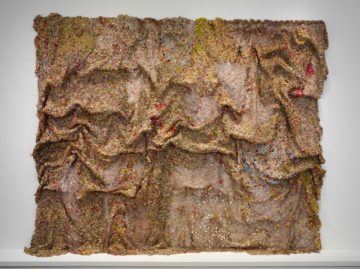

Archaeologists believe they have discovered the world’s oldest-known representational artwork: three wild pigs painted deep in a limestone cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi at least 45,500 years ago. Anatsui, a seventy-six-year-old Ghanaian sculptor based in Nigeria, has transfigured many grand spaces with his cascading metal mosaics. Museums don them like regalia, as though to signal their graduation into an enlightened cosmopolitan modernity; they have graced, among other landmarks, the façades of London’s Royal Academy, Venice’s Museo Fortuny, and Marrakech’s El Badi Palace. The sheets sell for millions, attracting collectors as disparate as moma, the Vatican, and Bloomberg L.P. In the past ten years, public fascination with their medium’s trash-to-treasure novelty has matured into a broader appreciation of Anatsui’s significance. The man who dazzled with a formal trick may also be the exemplary sculptor of our precariously networked world.

Anatsui, a seventy-six-year-old Ghanaian sculptor based in Nigeria, has transfigured many grand spaces with his cascading metal mosaics. Museums don them like regalia, as though to signal their graduation into an enlightened cosmopolitan modernity; they have graced, among other landmarks, the façades of London’s Royal Academy, Venice’s Museo Fortuny, and Marrakech’s El Badi Palace. The sheets sell for millions, attracting collectors as disparate as moma, the Vatican, and Bloomberg L.P. In the past ten years, public fascination with their medium’s trash-to-treasure novelty has matured into a broader appreciation of Anatsui’s significance. The man who dazzled with a formal trick may also be the exemplary sculptor of our precariously networked world. I just published a novel in Norway two months ago. I’m now writing another novel which somehow is related, and I’ve started it, I’ve written a hundred pages or so, so I’m in the middle of the beginning of that, which is the hardest part. But that’s what I’m doing.

I just published a novel in Norway two months ago. I’m now writing another novel which somehow is related, and I’ve started it, I’ve written a hundred pages or so, so I’m in the middle of the beginning of that, which is the hardest part. But that’s what I’m doing. In 1972,

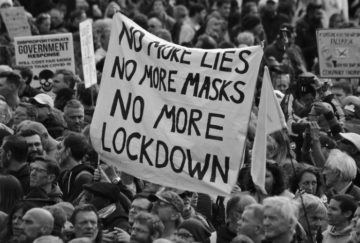

In 1972,  Over the past year, mobilizations around the world have sprung up against governmental efforts to contain the coronavirus through lockdowns, social distancing guidelines, mask mandates, and vaccines. Led in many cases by angry freelancers and the self-employed, amplified by entrepreneurs of speculative and totalizing prophecies, these movements are less what José Ortega y Gasset called “the revolt of the masses” and more “the revolt of the Mittelstand”—small- and medium-sized businesses. In comparison to the populism that dominated discussion in 2017, they are less tethered to mediagenic leaders and parties, slipperier on the traditional political spectrum, and less fixated on the assumption of state power. The spectacular and deadly storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6 has understandably eclipsed all other mobilizations for the moment. Yet, by drawing back the lens, we can see where aspects of a narrowly defined Trumpism overlap with a broader global phenomenon—and where they do not.

Over the past year, mobilizations around the world have sprung up against governmental efforts to contain the coronavirus through lockdowns, social distancing guidelines, mask mandates, and vaccines. Led in many cases by angry freelancers and the self-employed, amplified by entrepreneurs of speculative and totalizing prophecies, these movements are less what José Ortega y Gasset called “the revolt of the masses” and more “the revolt of the Mittelstand”—small- and medium-sized businesses. In comparison to the populism that dominated discussion in 2017, they are less tethered to mediagenic leaders and parties, slipperier on the traditional political spectrum, and less fixated on the assumption of state power. The spectacular and deadly storming of the U.S. Capitol on January 6 has understandably eclipsed all other mobilizations for the moment. Yet, by drawing back the lens, we can see where aspects of a narrowly defined Trumpism overlap with a broader global phenomenon—and where they do not.