Adam Tooze over at Substack:

I was forced to talk about bitcoin this week. On a podcast (in German).

The discussion was triggered by the remarkable surge in bitcoin’s value – the second great surge in the Ur-crypto’s turbulent history since it’s launch on 3 January 2009.

Lisa Splanemann, the journalist with whom I do the podcast, has been pushing the topic for a while. I was reluctant.

Money talk is political talk. We should be selective in the political talk we engage in. I don’t like the politics of crypto/bitcoin.

Money is an expression of social power. In particular, it is an amalgam of the power and confidence leveraged by the state and capital. All actual monies, whatever form they are cast in, have an element of “fiat” about them.

As the Merriman-Webster dictionary helpfully explains: “fiat: a command or act of will that creates something without or as if without further effort. According to the Bible, the world was created by fiat.”

The fiat money world is the world that we have inhabited since the collapse of the Bretton Woods system between 1971 and 1973. It is normally contrasted to the gold standard world that preceded it. But are gold and “fiat” really that different? To back a currency with gold is a political choice too, anchored in structures of expectation on the part of creditors, debtors and investors, on systems for gold production, storage, relationships between banks and central banks, in other words structures of power.

More here.

Branko Milanovic in Foreign Affairs:

Branko Milanovic in Foreign Affairs: Jane Hu in Bookforum:

Jane Hu in Bookforum: Joanna Wuest in Psyche:

Joanna Wuest in Psyche: AMONG THE MANY ENTRIES in Edwin Frank’s increasingly encyclopedic New York Review Books Classics series is a genre of postwar European memoir: informed by psychoanalysis, ironic in tone or form, and of subject matter that’s both bourgeois and aristocratic—or at the intersections where upwardly moving middle classes and downwardly mobile inherited scions most resemble each other. Gregor von Rezzori’s Memoirs of an Anti-Semite, J. R. Ackerley’s My Father and Myself, Jessica Mitford’s Hons and Rebels: these books record their authors’ efforts to collect the pieces and resolve mysteries of their childhoods and adolescence—a task often complicated by the shattering impact of the Second World War—and have also become documents in their own right, testaments not only to a bygone world but to a bygone way of reckoning with privilege, secrets, desire, belonging, and money. Richard Wollheim’s Germs, first published posthumously in 2004, hits all these notes: his parents’ somewhat open marriage, his lower-class granny, his immersion in a milieu of genuine artists, appreciators, and pompous hucksters and hustlers, sometimes united in the same person. Wollheim was still fine-tuning the manuscript when he died in 2003, at eighty, and what we have is mostly organized around the childhood and adolescent years before he arrived at Oxford, though with occasional associative leaps forward and backward in time.

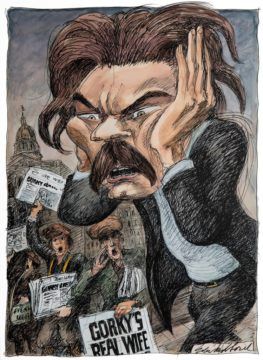

AMONG THE MANY ENTRIES in Edwin Frank’s increasingly encyclopedic New York Review Books Classics series is a genre of postwar European memoir: informed by psychoanalysis, ironic in tone or form, and of subject matter that’s both bourgeois and aristocratic—or at the intersections where upwardly moving middle classes and downwardly mobile inherited scions most resemble each other. Gregor von Rezzori’s Memoirs of an Anti-Semite, J. R. Ackerley’s My Father and Myself, Jessica Mitford’s Hons and Rebels: these books record their authors’ efforts to collect the pieces and resolve mysteries of their childhoods and adolescence—a task often complicated by the shattering impact of the Second World War—and have also become documents in their own right, testaments not only to a bygone world but to a bygone way of reckoning with privilege, secrets, desire, belonging, and money. Richard Wollheim’s Germs, first published posthumously in 2004, hits all these notes: his parents’ somewhat open marriage, his lower-class granny, his immersion in a milieu of genuine artists, appreciators, and pompous hucksters and hustlers, sometimes united in the same person. Wollheim was still fine-tuning the manuscript when he died in 2003, at eighty, and what we have is mostly organized around the childhood and adolescent years before he arrived at Oxford, though with occasional associative leaps forward and backward in time. In April 1906, Czar Nicholas caved in to protests from around the world, and released Maxim Gorky from the prison into which he had thrown him. Mark Twain and other writers, hearing that the celebrated author of “The Lower Depths” had been freed, invited him to New York City, and Gorky, still harassed by the secret police, accepted. With him on the voyage was the actress Maria Andreyeva.

In April 1906, Czar Nicholas caved in to protests from around the world, and released Maxim Gorky from the prison into which he had thrown him. Mark Twain and other writers, hearing that the celebrated author of “The Lower Depths” had been freed, invited him to New York City, and Gorky, still harassed by the secret police, accepted. With him on the voyage was the actress Maria Andreyeva. Elizabeth Kolbert’s favourite movie is the end-of-the-world comedy

Elizabeth Kolbert’s favourite movie is the end-of-the-world comedy  I’d read “Lolita” in college, and I was too lazy to bother to read it again when preparing for my part in “The Bookshop.” I was already a huge fan of Nabokov’s — I had bought copies of his memoir, “Speak, Memory,” in bulk to hand out to my friends at college, and I had worn thin his “Lectures on Russian Literature,” which are as withering as they are brilliant. (I’ll never forget my shocked delight at his excoriation of Dostoyevsky as “a mediocre writer with wastelands of literary platitudes.”)

I’d read “Lolita” in college, and I was too lazy to bother to read it again when preparing for my part in “The Bookshop.” I was already a huge fan of Nabokov’s — I had bought copies of his memoir, “Speak, Memory,” in bulk to hand out to my friends at college, and I had worn thin his “Lectures on Russian Literature,” which are as withering as they are brilliant. (I’ll never forget my shocked delight at his excoriation of Dostoyevsky as “a mediocre writer with wastelands of literary platitudes.”) Does history have a goal? Is it possible that all the human societies that existed are ultimately a prelude to establishing a system where one entity will govern everything the world over? The Oxford University philosopher

Does history have a goal? Is it possible that all the human societies that existed are ultimately a prelude to establishing a system where one entity will govern everything the world over? The Oxford University philosopher  Why did prescription opioids bring so much misery to the small towns of postindustrial America?

Why did prescription opioids bring so much misery to the small towns of postindustrial America? Despite his stature as a giant of Soviet Ukrainian literature, Bazhan remains all but unknown outside Ukraine. His work is formally sophisticated, his language rich, his subject matter multilayered. Translating him is, thus, no mean feat. But on top of that, for much of the 20th century, Bazhan’s pre-Party existence, and thus much of his best work, was unknown or inaccessible to potential translators. It is fitting, then, that the editors of this new volume of Bazhan’s work, Oksana Rosenblum, Lev Fridman, and Anzhelika Khyzhnia, have turned to the poet’s earlier poetry. The volume takes us through selections from Bazhan’s first three books, published in the giddy experimental atmosphere of the 1920s, before tackling some longer and more formally, thematically, and politically complex works from the early 1930s. Indeed, one of the most fascinating aspects of this book is the way it reveals the tension between Bazhan’s mercurial, untrammeled poetic genius and the creeping ideological strictures of Stalinism.

Despite his stature as a giant of Soviet Ukrainian literature, Bazhan remains all but unknown outside Ukraine. His work is formally sophisticated, his language rich, his subject matter multilayered. Translating him is, thus, no mean feat. But on top of that, for much of the 20th century, Bazhan’s pre-Party existence, and thus much of his best work, was unknown or inaccessible to potential translators. It is fitting, then, that the editors of this new volume of Bazhan’s work, Oksana Rosenblum, Lev Fridman, and Anzhelika Khyzhnia, have turned to the poet’s earlier poetry. The volume takes us through selections from Bazhan’s first three books, published in the giddy experimental atmosphere of the 1920s, before tackling some longer and more formally, thematically, and politically complex works from the early 1930s. Indeed, one of the most fascinating aspects of this book is the way it reveals the tension between Bazhan’s mercurial, untrammeled poetic genius and the creeping ideological strictures of Stalinism. It’s a little-known fact that Camus worked briefly as a meteorologist. For almost a year, from 1937-38, he wore a lab coat at the Algiers Geophysics Institute and catalogued measurements of atmospheric pressure from hundreds of weather stations across North Africa. The data had been piling up, and despite the arrogance of their imperial ambitions, the men who ran the Institute couldn’t attract enough funding. They didn’t have the money to hire a scientist trained for this “exacting and, in effect, stupefying task.”

It’s a little-known fact that Camus worked briefly as a meteorologist. For almost a year, from 1937-38, he wore a lab coat at the Algiers Geophysics Institute and catalogued measurements of atmospheric pressure from hundreds of weather stations across North Africa. The data had been piling up, and despite the arrogance of their imperial ambitions, the men who ran the Institute couldn’t attract enough funding. They didn’t have the money to hire a scientist trained for this “exacting and, in effect, stupefying task.” It’s early, but Republicans have already seized on their strategy for winning the 2022 and 2024 elections. Of course, it does not depend on mundane tactics like “running on their record” or “making robust arguments about how their policies are better than their opponents.” The GOP is instead returning to the well that has, time and again, paid off handsomely: feigning umbrage over culture war flashpoints, usually ones wholly invented by the right or propped up with lies, to distract from substantive policy debates that actually impact American lives.

It’s early, but Republicans have already seized on their strategy for winning the 2022 and 2024 elections. Of course, it does not depend on mundane tactics like “running on their record” or “making robust arguments about how their policies are better than their opponents.” The GOP is instead returning to the well that has, time and again, paid off handsomely: feigning umbrage over culture war flashpoints, usually ones wholly invented by the right or propped up with lies, to distract from substantive policy debates that actually impact American lives. A new study asks the question: Do conversations end when people want them to? The short answer, it turns out, is no. The study, published this week in the journal the

A new study asks the question: Do conversations end when people want them to? The short answer, it turns out, is no. The study, published this week in the journal the  How can we summarise the Covid year from a broad historical perspective? Many people believe that the terrible toll coronavirus has taken demonstrates humanity’s helplessness in the face of nature’s might. In fact, 2020 has shown that humanity is far from helpless. Epidemics are no longer uncontrollable forces of nature. Science has turned them into a manageable challenge.

How can we summarise the Covid year from a broad historical perspective? Many people believe that the terrible toll coronavirus has taken demonstrates humanity’s helplessness in the face of nature’s might. In fact, 2020 has shown that humanity is far from helpless. Epidemics are no longer uncontrollable forces of nature. Science has turned them into a manageable challenge.