Nathan Shields at The Baffler:

Mann contended that Wagner’s art was neither monolithically grand nor sinister but deeply, violently ambivalent. He cited Nietzsche’s swing from filial devotion to Oedipal rebellion as a case in point. In his first major work, The Birth of Tragedy (1872), Nietzsche hailed his friend’s art in terms that fused Wagner’s own revolutionary rhetoric with Schopenhauer’s metaphysics of self-annihilation: it broke the “spell of individuation,” reopening the way to “the innermost heart of things.” But over the following decade Nietzsche shifted slowly from acolyte to skeptic, estranged by Wagner’s growing nationalism, the spectacle of Bayreuth, and his own changing intellectual needs. The final breach, he wrote, was precipitated by the self-betrayal of Parsifal, in which “Wagner, seemingly the all-conquering, actually a decaying, despairing decadent, suddenly sank down helpless and shattered before the Christian cross.” Later, in The Case of Wagner (1888), Nietzsche concluded that there had been nothing there to betray in the first place. Wagner had always been a disease, a toxin, and a neurosis, even before the encounter with Schopenhauer. “Only the philosopher of decadence gave to the artist of decadence—himself.”

Mann contended that Wagner’s art was neither monolithically grand nor sinister but deeply, violently ambivalent. He cited Nietzsche’s swing from filial devotion to Oedipal rebellion as a case in point. In his first major work, The Birth of Tragedy (1872), Nietzsche hailed his friend’s art in terms that fused Wagner’s own revolutionary rhetoric with Schopenhauer’s metaphysics of self-annihilation: it broke the “spell of individuation,” reopening the way to “the innermost heart of things.” But over the following decade Nietzsche shifted slowly from acolyte to skeptic, estranged by Wagner’s growing nationalism, the spectacle of Bayreuth, and his own changing intellectual needs. The final breach, he wrote, was precipitated by the self-betrayal of Parsifal, in which “Wagner, seemingly the all-conquering, actually a decaying, despairing decadent, suddenly sank down helpless and shattered before the Christian cross.” Later, in The Case of Wagner (1888), Nietzsche concluded that there had been nothing there to betray in the first place. Wagner had always been a disease, a toxin, and a neurosis, even before the encounter with Schopenhauer. “Only the philosopher of decadence gave to the artist of decadence—himself.”

more here.

We were the unwanted, the unneeded and the unseen, invisible to all but ourselves.” And with those words he is back, the “man of two faces and two minds” as well as many guises: Vietnamese, French, American, soldier, academic, Japanese tourist, waiter, hoodlum, killer, communist, capitalist, spy. In 2016 the unnamed protagonist of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s first novel

We were the unwanted, the unneeded and the unseen, invisible to all but ourselves.” And with those words he is back, the “man of two faces and two minds” as well as many guises: Vietnamese, French, American, soldier, academic, Japanese tourist, waiter, hoodlum, killer, communist, capitalist, spy. In 2016 the unnamed protagonist of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s first novel  Deep in the

Deep in the The first time I heard the name Thomas Sowell was during that bitterly partisan—though in retrospect, comparatively tame—transition period from George W. Bush to Barack Obama. My mother’s younger sister, a gun-owning, born-again evangelical Christian and staunchly Republican voter from Southern California had by then become an active and vocal Facebook user. In those days, I was half a decade out of undergrad, living in New York City, making my first forays into the world of professional opinion-having. I felt my first (and, it would turn out, my last) stirrings of political romanticism in my exuberance over the candidacy and election of the first black president. Suffice it to say we locked digital horns on a regular basis. “It’s not about color for me,” my aunt said while railing against Obama. “For example, I love Thomas Sowell.”

The first time I heard the name Thomas Sowell was during that bitterly partisan—though in retrospect, comparatively tame—transition period from George W. Bush to Barack Obama. My mother’s younger sister, a gun-owning, born-again evangelical Christian and staunchly Republican voter from Southern California had by then become an active and vocal Facebook user. In those days, I was half a decade out of undergrad, living in New York City, making my first forays into the world of professional opinion-having. I felt my first (and, it would turn out, my last) stirrings of political romanticism in my exuberance over the candidacy and election of the first black president. Suffice it to say we locked digital horns on a regular basis. “It’s not about color for me,” my aunt said while railing against Obama. “For example, I love Thomas Sowell.” To that side of my extended family, I became the stereotype of a coastal liberal, writing for the New York Times and wholly out of touch with the real America. In fact, I’ve always prided and defined myself as an anti-tribal thinker, and sometime contrarian, working firmly within a left-of-center black tradition—a tradition populated by brave and brilliant minds from Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray to Harold Cruse, Stanley Crouch, Orlando Patterson, at times even Zadie Smith and James Baldwin.

To that side of my extended family, I became the stereotype of a coastal liberal, writing for the New York Times and wholly out of touch with the real America. In fact, I’ve always prided and defined myself as an anti-tribal thinker, and sometime contrarian, working firmly within a left-of-center black tradition—a tradition populated by brave and brilliant minds from Ralph Ellison and Albert Murray to Harold Cruse, Stanley Crouch, Orlando Patterson, at times even Zadie Smith and James Baldwin. JOAN MITCHELL’S PAINTINGS from the late 1950s have space in them. They are big surfaces covered with marks, like most Abstract Expressionist paintings made in New York in the same decade, and so they look much flatter than a carefully measured perspectival scene from the 1940s by, for example, Edward Hopper. But compared with almost everything her most productive and now famous peers were doing at the same time, Mitchell’s paintings are practically voluminous.

JOAN MITCHELL’S PAINTINGS from the late 1950s have space in them. They are big surfaces covered with marks, like most Abstract Expressionist paintings made in New York in the same decade, and so they look much flatter than a carefully measured perspectival scene from the 1940s by, for example, Edward Hopper. But compared with almost everything her most productive and now famous peers were doing at the same time, Mitchell’s paintings are practically voluminous. “EVERYBODY BEHAVES BADLY,” says Hemingway’s Jake Barnes. “Give them the proper chance.” Why read novels about people behaving badly? Can a novel about bad people do readers good? These questions about the real-world effects of fictional characters — not just their “reality effects” — have come to the fore in recent years with the ascendancy of autofiction, on the one hand, and the persistence of the stoutly character-driven novel, on the other: the kind where characters, and, by extension, readers, get to know, and accept, social others who are nothing like them. Whereas autofiction asserts a kind of apolitical license — it’s my life, so it doesn’t matter if my problems seem trivial and if everyone I know is exactly like me — it’s incumbent on the latter kind of novelist to make social difference legible, rather than erasing or tokenizing it. It’s a tall order, and between the demands of professional and lay critics, on and off Twitter, the bar for ethical fiction, in which characterization is the vehicle for moral instruction, keeps getting raised ever higher.

“EVERYBODY BEHAVES BADLY,” says Hemingway’s Jake Barnes. “Give them the proper chance.” Why read novels about people behaving badly? Can a novel about bad people do readers good? These questions about the real-world effects of fictional characters — not just their “reality effects” — have come to the fore in recent years with the ascendancy of autofiction, on the one hand, and the persistence of the stoutly character-driven novel, on the other: the kind where characters, and, by extension, readers, get to know, and accept, social others who are nothing like them. Whereas autofiction asserts a kind of apolitical license — it’s my life, so it doesn’t matter if my problems seem trivial and if everyone I know is exactly like me — it’s incumbent on the latter kind of novelist to make social difference legible, rather than erasing or tokenizing it. It’s a tall order, and between the demands of professional and lay critics, on and off Twitter, the bar for ethical fiction, in which characterization is the vehicle for moral instruction, keeps getting raised ever higher. Months of lockdowns and waves of surging Covid cases throughout last year shuttered clinics and testing labs, or reduced hours at other places, resulting in steep declines in the number of screenings, including for breast and colorectal cancers, experts have said. Numerous studies showed that the number of patients screened or given a diagnosis of cancer fell during the early months of the pandemic. By mid-June, the rate of screenings for breast, colon and cervical cancers were still 29 percent to 36 percent lower than their prepandemic levels, according to

Months of lockdowns and waves of surging Covid cases throughout last year shuttered clinics and testing labs, or reduced hours at other places, resulting in steep declines in the number of screenings, including for breast and colorectal cancers, experts have said. Numerous studies showed that the number of patients screened or given a diagnosis of cancer fell during the early months of the pandemic. By mid-June, the rate of screenings for breast, colon and cervical cancers were still 29 percent to 36 percent lower than their prepandemic levels, according to  Scientists have made fabrics from polythene in a move they say could reduce plastic pollution and make the fashion industry more sustainable. Polythene is a ubiquitous plastic, found in everything from plastic bags to food packaging. The new textiles have potential uses in sports wear, and even high-end fashion, according to US researchers. The plastic “cloth” is more environmentally-friendly than natural fibres, and can be recycled, they say. Dr Svetlana Boriskina, from the department of engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, US, said plastic bags that nobody wants can be turned into high-performance fabrics with a low environmental footprint. “There’s no reason why the simple plastic bag cannot be made into fibre and used as a high-end garment,” she told BBC News. “You can go literally from trash to a high-performance garment that provides comfort and can be recycled multiple times back into a new garment.”

Scientists have made fabrics from polythene in a move they say could reduce plastic pollution and make the fashion industry more sustainable. Polythene is a ubiquitous plastic, found in everything from plastic bags to food packaging. The new textiles have potential uses in sports wear, and even high-end fashion, according to US researchers. The plastic “cloth” is more environmentally-friendly than natural fibres, and can be recycled, they say. Dr Svetlana Boriskina, from the department of engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, US, said plastic bags that nobody wants can be turned into high-performance fabrics with a low environmental footprint. “There’s no reason why the simple plastic bag cannot be made into fibre and used as a high-end garment,” she told BBC News. “You can go literally from trash to a high-performance garment that provides comfort and can be recycled multiple times back into a new garment.” In the summer of 1973 Time magazine decided not to run a piece that it had commissioned,

In the summer of 1973 Time magazine decided not to run a piece that it had commissioned,  When Avi Wigderson and László Lovász began their careers in the 1970s, theoretical computer science and pure mathematics were almost entirely separate disciplines. Today, they’ve grown so close it’s hard to find the line between them. For their many fundamental contributions to both fields, and for their work drawing them together, today Lovász and Wigderson were awarded the

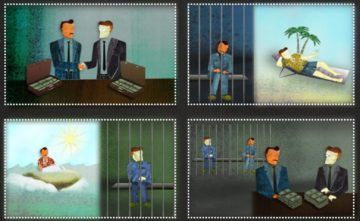

When Avi Wigderson and László Lovász began their careers in the 1970s, theoretical computer science and pure mathematics were almost entirely separate disciplines. Today, they’ve grown so close it’s hard to find the line between them. For their many fundamental contributions to both fields, and for their work drawing them together, today Lovász and Wigderson were awarded the  When and why do people cooperate or compete? Researchers at the RAND Corporation studied this question in the 1950s using what was then a new decision science called game theory. Game theory was developed during World War II by the Hungarian mathematical physicist and leading Manhattan Project contributor John von Neumann and the Austrian economist Oskar Morgenstern. It was immediately used by operations researchers for military logistics, and to develop a science of military decision making. By the late 1950s it was applied to nuclear deterrence, with the future Nobel laureate economist Thomas Schelling publishing The Strategy of Conflict in 1960.

When and why do people cooperate or compete? Researchers at the RAND Corporation studied this question in the 1950s using what was then a new decision science called game theory. Game theory was developed during World War II by the Hungarian mathematical physicist and leading Manhattan Project contributor John von Neumann and the Austrian economist Oskar Morgenstern. It was immediately used by operations researchers for military logistics, and to develop a science of military decision making. By the late 1950s it was applied to nuclear deterrence, with the future Nobel laureate economist Thomas Schelling publishing The Strategy of Conflict in 1960. In a paper published in Nature Neuroscience last week, University of Pittsburgh researchers described how reward signals in the brain are modulated by uncertainty. Dopamine signals are intertwined with reward learning; they teach the brain which cues or actions predict the best rewards. New findings from the Stauffer lab at Pitt School of Medicine indicate that dopamine signals also reflect the certainty surrounding reward predictions. In short, dopamine signals might teach the brain about the likelihood of getting a reward.

In a paper published in Nature Neuroscience last week, University of Pittsburgh researchers described how reward signals in the brain are modulated by uncertainty. Dopamine signals are intertwined with reward learning; they teach the brain which cues or actions predict the best rewards. New findings from the Stauffer lab at Pitt School of Medicine indicate that dopamine signals also reflect the certainty surrounding reward predictions. In short, dopamine signals might teach the brain about the likelihood of getting a reward. David Wyatt has worked in public relations for more than 20 years, having worked his way up to become a senior vice-president at an Austin, Texas-based firm. He recognises his privileges as a

David Wyatt has worked in public relations for more than 20 years, having worked his way up to become a senior vice-president at an Austin, Texas-based firm. He recognises his privileges as a  Mississippi John Hurt, Cab Calloway, Woody Guthrie, James Brown, Wilson Pickett, Tina Turner, Bob Dylan, and Beck are among the hundreds who have sung a version of Stagolee’s story. Lloyd Price took a rollicking rendition of “Stagger Lee” to the top of the pop charts in 1959. Such brushes with mainstream success never compromised Stag’s street cred, though. In bars, barbershops, and prisons, he remained “the baddest n—– who ever lived,” the antihero of profane epics and rhyming “toasts” whose exploits offered a fantasy of freedom from life’s indignities. Stagolee haunts the prose of Richard Wright and Toni Morrison; James Baldwin worked on a novel about the character and late in his life published a long poem called “Staggerlee Wonders.”

Mississippi John Hurt, Cab Calloway, Woody Guthrie, James Brown, Wilson Pickett, Tina Turner, Bob Dylan, and Beck are among the hundreds who have sung a version of Stagolee’s story. Lloyd Price took a rollicking rendition of “Stagger Lee” to the top of the pop charts in 1959. Such brushes with mainstream success never compromised Stag’s street cred, though. In bars, barbershops, and prisons, he remained “the baddest n—– who ever lived,” the antihero of profane epics and rhyming “toasts” whose exploits offered a fantasy of freedom from life’s indignities. Stagolee haunts the prose of Richard Wright and Toni Morrison; James Baldwin worked on a novel about the character and late in his life published a long poem called “Staggerlee Wonders.”