Arik Kershenbaum in The New York Times:

Is anybody else out there? For as long as humans have recognized Earth as but one planet in a vast, orb-speckled universe, we have pondered the mystery of extraterrestrial life. After Nicolaus Copernicus introduced heliocentric theory to 16th century Europe, astronomers began to dream about “other worlds” — and populate them with imaginary creatures. Pioneering astronomers such as Johannes Kepler (father of planetary motion) and William Herschel (discoverer of Uranus) believed in the existence of alien life. Peering through his telescope, Herschel thought he spied towns and forests on the lunar surface. We’re still looking. In 2017, a mysterious object named “Oumuamua” was observed passing through our solar system and some astronomers have made the controversial suggestion that it may be a scout probe sent by an alien civilization. In February, the NASA Mars Perseverance Rover landed on the red planet to search for traces of ancient microbial life.

Is anybody else out there? For as long as humans have recognized Earth as but one planet in a vast, orb-speckled universe, we have pondered the mystery of extraterrestrial life. After Nicolaus Copernicus introduced heliocentric theory to 16th century Europe, astronomers began to dream about “other worlds” — and populate them with imaginary creatures. Pioneering astronomers such as Johannes Kepler (father of planetary motion) and William Herschel (discoverer of Uranus) believed in the existence of alien life. Peering through his telescope, Herschel thought he spied towns and forests on the lunar surface. We’re still looking. In 2017, a mysterious object named “Oumuamua” was observed passing through our solar system and some astronomers have made the controversial suggestion that it may be a scout probe sent by an alien civilization. In February, the NASA Mars Perseverance Rover landed on the red planet to search for traces of ancient microbial life.

The search field is incomprehensibly large: Astronomers estimate that there are more than 100 billion planets in the Milky Way alone — plus exponentially more in the rest of the universe.

What might we find elsewhere?

One zoologist suggests some answers actually may be hiding in plain sight, right here at home. In a provocative new book, “The Zoologist’s Guide to the Galaxy,” Arik Kershenbaum contends that life on Earth provides hints of what we might expect to find on other planets.

Kershenbaum, a scientist at the University of Cambridge, asserts that the “universal laws of biology” that govern life on Earth also apply to aliens. The most important is that species evolve by natural selection, the bedrock idea of evolutionary biology proposed by Charles Darwin. No matter how alien biochemistry might work and no matter how planetary environments might differ, Kershenbaum argues that some version of Darwinian selection would be at work — and would have channelled alien evolution to restricted menus of possibilities.

More here.

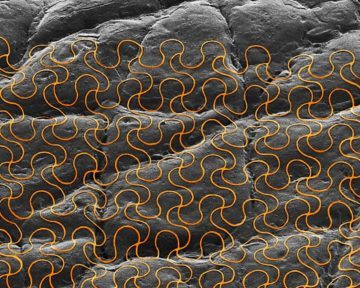

Materials scientists aren’t the first people you’d think would be pulled into the fight against COVID-19. But that’s what happened to John Rogers. He leads a team at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, that develops soft, flexible, skin-like materials with health-monitoring applications. One device, designed to sit in the hollow at the base of the throat, is a wireless, Bluetooth-connected piece of polymer and circuitry that provides real-time monitoring of talking, breathing, heart rate and other vital signs, which could be used in individuals who have had a stroke and require speech therapy

Materials scientists aren’t the first people you’d think would be pulled into the fight against COVID-19. But that’s what happened to John Rogers. He leads a team at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, that develops soft, flexible, skin-like materials with health-monitoring applications. One device, designed to sit in the hollow at the base of the throat, is a wireless, Bluetooth-connected piece of polymer and circuitry that provides real-time monitoring of talking, breathing, heart rate and other vital signs, which could be used in individuals who have had a stroke and require speech therapy At Vancouver’s University of British Columbia, the Brock Commons Tallwood House, sheathed in sleek blond wood, stands out among the neighboring gray concrete towers. This striking facade isn’t just an aesthetic choice. When it opened in 2017, the 18-story residence hall was the tallest building constructed of timber in the world. Erected from prefabricated components in just 70 days, it was faster and cheaper to build than a conventional building. What’s more, its material saved over 2,400 metric tons of carbon emissions.

At Vancouver’s University of British Columbia, the Brock Commons Tallwood House, sheathed in sleek blond wood, stands out among the neighboring gray concrete towers. This striking facade isn’t just an aesthetic choice. When it opened in 2017, the 18-story residence hall was the tallest building constructed of timber in the world. Erected from prefabricated components in just 70 days, it was faster and cheaper to build than a conventional building. What’s more, its material saved over 2,400 metric tons of carbon emissions. This is the “demarcation problem,” as the Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper famously called it. The solution is not at all obvious. You cannot just rely on those parts of science that are correct, since science is a work in progress. Much of what scientists claim is provisional, after all, and often turns out to be wrong. That does not mean those who were wrong were engaged in “pseudoscience,” or even that they were doing “bad science”—this is just how science operates. What makes a theory scientific is something other than the fact that it is right.

This is the “demarcation problem,” as the Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper famously called it. The solution is not at all obvious. You cannot just rely on those parts of science that are correct, since science is a work in progress. Much of what scientists claim is provisional, after all, and often turns out to be wrong. That does not mean those who were wrong were engaged in “pseudoscience,” or even that they were doing “bad science”—this is just how science operates. What makes a theory scientific is something other than the fact that it is right. In Muslim communities, homosexuality is intrinsically linked to anxiety, intimidation, violence, and, in some cases, death. For many, it involves living a closeted existence for fear of being ostracised or disowned. Islamic theological teachings, disseminated by religious institutions and espoused by community leaders, range from preaching for our execution to advising us to live a life of celibacy. Yet voices on the left, historically a stronghold of LGBTI support, do not sufficiently decry the abysmal treatment of gay and bi people of Muslim heritage, nor do they adequately mobilize against this specific and brutal form of homophobia.

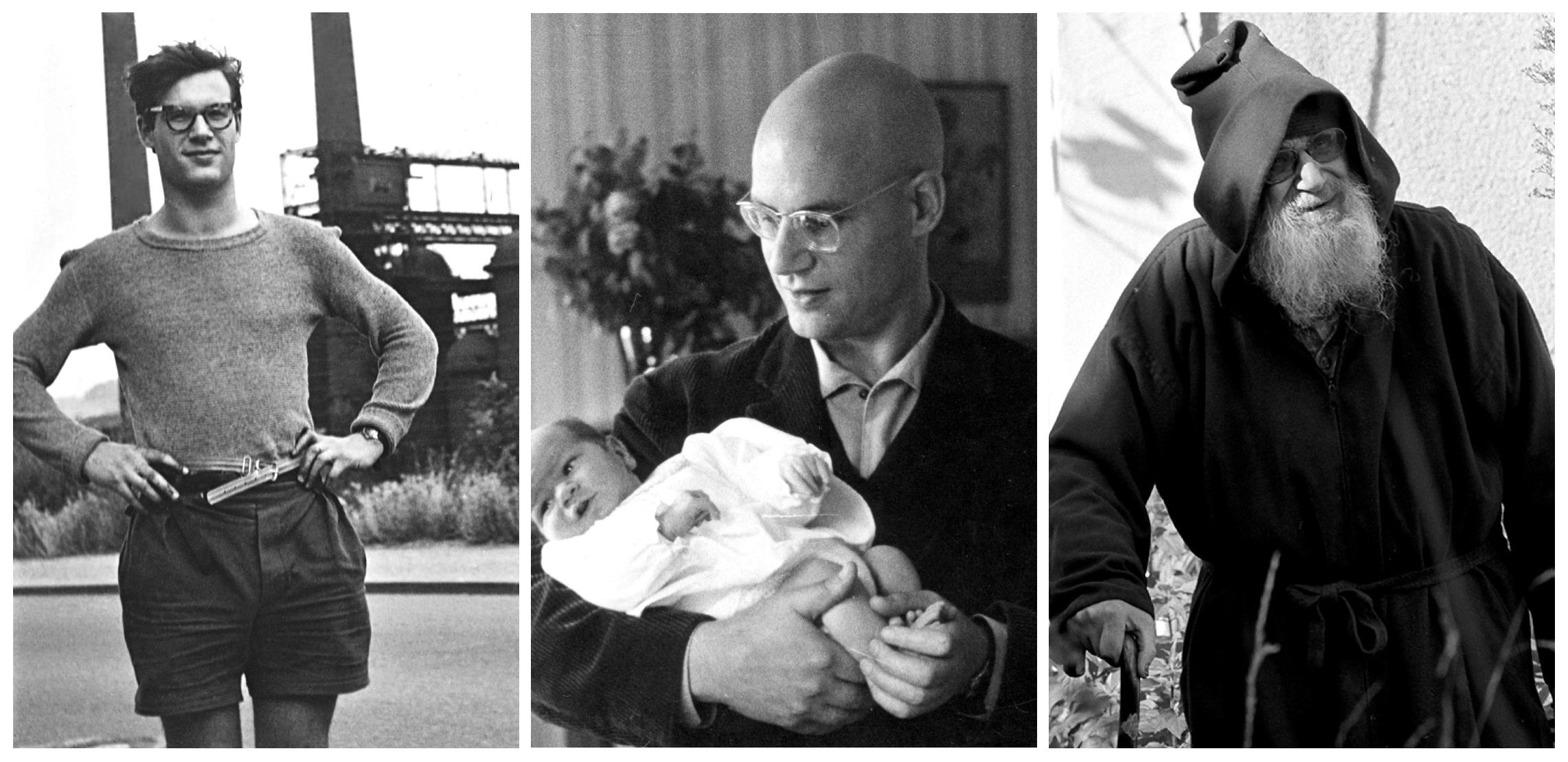

In Muslim communities, homosexuality is intrinsically linked to anxiety, intimidation, violence, and, in some cases, death. For many, it involves living a closeted existence for fear of being ostracised or disowned. Islamic theological teachings, disseminated by religious institutions and espoused by community leaders, range from preaching for our execution to advising us to live a life of celibacy. Yet voices on the left, historically a stronghold of LGBTI support, do not sufficiently decry the abysmal treatment of gay and bi people of Muslim heritage, nor do they adequately mobilize against this specific and brutal form of homophobia. In 1947, Kurt Gödel, Albert Einstein, and Oskar Morgenstern drove from Princeton to Trenton in Morgenstern’s car. The three men, who’d fled Nazi Europe and become close friends at the Institute for Advanced Study, were on their way to a courthouse where Gödel, an Austrian exile, was scheduled to take the U.S.-citizenship exam, something his two friends had done already. Morgenstern had founded game theory, Einstein had founded the theory of relativity, and Gödel, the greatest logician since Aristotle, had revolutionized mathematics and philosophy with his incompleteness theorems. Morgenstern drove. Gödel sat in the back. Einstein, up front with Morgenstern, turned around and said, teasing, “Now, Gödel, are you really well prepared for this examination?” Gödel looked stricken.

In 1947, Kurt Gödel, Albert Einstein, and Oskar Morgenstern drove from Princeton to Trenton in Morgenstern’s car. The three men, who’d fled Nazi Europe and become close friends at the Institute for Advanced Study, were on their way to a courthouse where Gödel, an Austrian exile, was scheduled to take the U.S.-citizenship exam, something his two friends had done already. Morgenstern had founded game theory, Einstein had founded the theory of relativity, and Gödel, the greatest logician since Aristotle, had revolutionized mathematics and philosophy with his incompleteness theorems. Morgenstern drove. Gödel sat in the back. Einstein, up front with Morgenstern, turned around and said, teasing, “Now, Gödel, are you really well prepared for this examination?” Gödel looked stricken. Natural selection seems, at first glance, to be so frustratingly inefficient. Generation after generation of baby gazelles are born, destined to be eaten by lions. Only by chance is one baby born with longer legs, able to run faster, and so escape being eaten. Of course, the very beauty of natural selection is that it doesn’t require any foresight; natural selection explains life in the universe precisely because there is no presumption of any prior knowledge. No Creator is necessary, because the evolutionary process is guaranteed to proceed even without any predefined rules. Life evolves—albeit slowly—without having to know where it’s going.

Natural selection seems, at first glance, to be so frustratingly inefficient. Generation after generation of baby gazelles are born, destined to be eaten by lions. Only by chance is one baby born with longer legs, able to run faster, and so escape being eaten. Of course, the very beauty of natural selection is that it doesn’t require any foresight; natural selection explains life in the universe precisely because there is no presumption of any prior knowledge. No Creator is necessary, because the evolutionary process is guaranteed to proceed even without any predefined rules. Life evolves—albeit slowly—without having to know where it’s going. An especially mysterious manifestation of the materiality of language in these poems is the projection of voice from, or into, the material world. Repeatedly, at special moments, things speak: “the hollyhocks spoke”; “Freezing rain with silver seems to be speaking”; “these colors speak”; “The sky speaks to me”; “The roofs speak”; “the room alive speaks when the corpse speaks… and the earth speaks”; “the trees and grass are speaking”; “the old sun / is speaking.” This eruption of voice from things—Gizzi calls it “thinging,” in a pun on “singing”—seems to mark that recovery of the world that Gizzi associates with elegy in the second “Now It’s Dark” poem. However, in the volume Now It’s Dark, that recovery is purchased at the price of another loss, that of “the speaking subject,” as it is called in psycholinguistic theory, or the one who says “I,” in the traditional view of lyric poetry. Drawing on that theory, Language writers accused lyric poetry of escaping into an illusory interior world inhabited by an equally illusory “I.”

An especially mysterious manifestation of the materiality of language in these poems is the projection of voice from, or into, the material world. Repeatedly, at special moments, things speak: “the hollyhocks spoke”; “Freezing rain with silver seems to be speaking”; “these colors speak”; “The sky speaks to me”; “The roofs speak”; “the room alive speaks when the corpse speaks… and the earth speaks”; “the trees and grass are speaking”; “the old sun / is speaking.” This eruption of voice from things—Gizzi calls it “thinging,” in a pun on “singing”—seems to mark that recovery of the world that Gizzi associates with elegy in the second “Now It’s Dark” poem. However, in the volume Now It’s Dark, that recovery is purchased at the price of another loss, that of “the speaking subject,” as it is called in psycholinguistic theory, or the one who says “I,” in the traditional view of lyric poetry. Drawing on that theory, Language writers accused lyric poetry of escaping into an illusory interior world inhabited by an equally illusory “I.” The world’s oldest known wooden sculpture — a nine-foot-tall totem pole thousands of years old — looms over a hushed chamber of an obscure Russian museum in the Ural Mountains, not far from the Siberian border. As mysterious as the huge stone figures of Easter Island, the Shigir Idol, as it is called, is a landscape of uneasy spirits that baffles the modern onlooker.

The world’s oldest known wooden sculpture — a nine-foot-tall totem pole thousands of years old — looms over a hushed chamber of an obscure Russian museum in the Ural Mountains, not far from the Siberian border. As mysterious as the huge stone figures of Easter Island, the Shigir Idol, as it is called, is a landscape of uneasy spirits that baffles the modern onlooker.

When you think about what separates humans from chimpanzees and other apes, you might think of our big brains, or the fact that we get around on two legs rather than four. But we have another distinguishing feature: water efficiency.

When you think about what separates humans from chimpanzees and other apes, you might think of our big brains, or the fact that we get around on two legs rather than four. But we have another distinguishing feature: water efficiency. Mathematician Alexander Grothendieck was born in 1928 to anarchist parents who left him to spend the majority of his formative years with foster parents. His father was murdered in Auschwitz. As his mother was detained, he grew up stateless, hiding from the Gestapo in occupied France. All the while, he taught himself mathematics from books and before his twentieth birthday had re-discovered for himself a proof of the

Mathematician Alexander Grothendieck was born in 1928 to anarchist parents who left him to spend the majority of his formative years with foster parents. His father was murdered in Auschwitz. As his mother was detained, he grew up stateless, hiding from the Gestapo in occupied France. All the while, he taught himself mathematics from books and before his twentieth birthday had re-discovered for himself a proof of the  Claudia Sahm over at INET:

Claudia Sahm over at INET: