Antonio Muñoz Molina at The Hudson Review:

I walk into the museum with a feeling of wonder as well as a slight sense of mistrust. I do not want to forget that it is a very recent invention. Thousands of years before the written book, or even before the birth of writing, the world was already filled with stories, with poems as elaborate as the Iliad, which in turn is almost new in comparison with Gilgamesh. The Prado, which was one of the first museums, is exactly two hundred years old, about the same age as the word “art” in the simultaneously sacral and restricted sense we bestow on it. The earliest known carved or painted images, on the other hand, were made over forty thousand years ago, and may have to be traced back still many more millennia if the dating of certain paintings attributed to Neanderthals is confirmed. If museums did not exist, if the term “art history” had never been coined, we would still have the wild horses of Chauvet, the heads and figures of the Cyclades, the whales, bears, and seals carved in ivory by the Inuit. We would still have Las Meninas, the wooden Christ of Medinaceli, the religious medals and cards that are worshipped and sold not far from here: Ladies of Sorrows; bloody effigies of Christ carried through town on the shoulders of a rapturously fervent Catholic crowd during Easter in the region where I was born; or the Holy Face, archaic and stern, that I used to see as a child in the cathedral of Jaén, a face that according to Church doctrine and common belief is not a painting made by the human hand but rather the true and miraculous impression of the face of Christ on the veil with which a woman named Veronica tried to wipe away his sweat and blood as he carried the Cross.

more here.

Feminist is not a descriptor she embraced until late in life (she died in 2002 at the age of seventy-one). Mostly, it’s a label that has been bestowed upon her in attempts to contend with her quixotic ambition. Her resistance to the term, though, derived not from a real quarrel with its meaning so much as from some murky combination of misunderstanding, eccentricity, and calculation. Her personal brand of rebellion emerged before the advent of the women’s movement proper, in the pregnant pause between the publication of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex in 1949 (when she was an eighteen-year-old fashion model about to marry her first husband, Harry Mathews) and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique in 1963, by which point Saint Phalle had already taken up arms against the church, the Father, and the picture plane. Her wrath against her family for her abusive, conformist upbringing, and her determination to revolt, in life and art, emerged independently of any movement or schooling. Hospitalized in 1953 after a suicide attempt—the low point of a psychic deterioration instigated by the realities of marriage and motherhood—she became an artist over the course of her six-week stay.

Feminist is not a descriptor she embraced until late in life (she died in 2002 at the age of seventy-one). Mostly, it’s a label that has been bestowed upon her in attempts to contend with her quixotic ambition. Her resistance to the term, though, derived not from a real quarrel with its meaning so much as from some murky combination of misunderstanding, eccentricity, and calculation. Her personal brand of rebellion emerged before the advent of the women’s movement proper, in the pregnant pause between the publication of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex in 1949 (when she was an eighteen-year-old fashion model about to marry her first husband, Harry Mathews) and Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique in 1963, by which point Saint Phalle had already taken up arms against the church, the Father, and the picture plane. Her wrath against her family for her abusive, conformist upbringing, and her determination to revolt, in life and art, emerged independently of any movement or schooling. Hospitalized in 1953 after a suicide attempt—the low point of a psychic deterioration instigated by the realities of marriage and motherhood—she became an artist over the course of her six-week stay. T

T The universe bets on disorder. Imagine, for example, dropping a thimbleful of red dye into a swimming pool. All of those dye molecules are going to slowly spread throughout the water. Physicists quantify this tendency to spread by counting the number of possible ways the dye molecules can be arranged. There’s one possible state where the molecules are crowded into the thimble. There’s another where, say, the molecules settle in a tidy clump at the pool’s bottom. But there are uncountable billions of permutations where the molecules spread out in different ways throughout the water. If the universe chooses from all the possible states at random, you can bet that it’s going to end up with one of the vast set of disordered possibilities. Seen in this way, the inexorable rise in entropy, or disorder, as quantified by the second law of thermodynamics, takes on an almost mathematical certainty. So of course physicists are constantly trying to break it.

The universe bets on disorder. Imagine, for example, dropping a thimbleful of red dye into a swimming pool. All of those dye molecules are going to slowly spread throughout the water. Physicists quantify this tendency to spread by counting the number of possible ways the dye molecules can be arranged. There’s one possible state where the molecules are crowded into the thimble. There’s another where, say, the molecules settle in a tidy clump at the pool’s bottom. But there are uncountable billions of permutations where the molecules spread out in different ways throughout the water. If the universe chooses from all the possible states at random, you can bet that it’s going to end up with one of the vast set of disordered possibilities. Seen in this way, the inexorable rise in entropy, or disorder, as quantified by the second law of thermodynamics, takes on an almost mathematical certainty. So of course physicists are constantly trying to break it. On arriving in Paris in 2013, I went to open a bank account. The personal banker assigned to me, who would remain with me for a few years after that, was a Senegalese immigrant, a proud professional, and most of all a proud Frenchwoman. When I showed her my immigration papers and my confirmation of employment by the University of Paris, she said something like, “Oh, sure, you’re one of the good immigrants.” I thought she had meant to speak damningly of the hypocrisy of her adoptive country, and I started to say, “You mean because I’m…”. But before I got to that color-coding adjective I wrongly presumed she had in mind, she completed her thought: “You’re one of the good immigrants, like me. You’ve got diplomas, you’ve got a job.” Then she pointed to the family of Roma people encamped on a styrofoam mattress on the sidewalk right outside: “Not like them,” she said, “they don’t want to work. It’s easier to just sit there and make people feel sorry for you.”

On arriving in Paris in 2013, I went to open a bank account. The personal banker assigned to me, who would remain with me for a few years after that, was a Senegalese immigrant, a proud professional, and most of all a proud Frenchwoman. When I showed her my immigration papers and my confirmation of employment by the University of Paris, she said something like, “Oh, sure, you’re one of the good immigrants.” I thought she had meant to speak damningly of the hypocrisy of her adoptive country, and I started to say, “You mean because I’m…”. But before I got to that color-coding adjective I wrongly presumed she had in mind, she completed her thought: “You’re one of the good immigrants, like me. You’ve got diplomas, you’ve got a job.” Then she pointed to the family of Roma people encamped on a styrofoam mattress on the sidewalk right outside: “Not like them,” she said, “they don’t want to work. It’s easier to just sit there and make people feel sorry for you.” “A way that math can make the world a better place is by making it a more interesting place to be a conscious being.” So says mathematician Emily Riehl near the start of this episode, and it’s a good summary of what’s to come. Emily works in realms of topology and category theory that are far away from practical applications, or even to some non-practical areas of theoretical physics. But they help us think about what is possible and how everything fits together, and what’s more interesting than that? We talk about what topology is, the specific example of homotopy — how things deform into other things — and how thinking about that leads us into groups, rings, groupoids, and ultimately to category theory, the most abstract of them all.

“A way that math can make the world a better place is by making it a more interesting place to be a conscious being.” So says mathematician Emily Riehl near the start of this episode, and it’s a good summary of what’s to come. Emily works in realms of topology and category theory that are far away from practical applications, or even to some non-practical areas of theoretical physics. But they help us think about what is possible and how everything fits together, and what’s more interesting than that? We talk about what topology is, the specific example of homotopy — how things deform into other things — and how thinking about that leads us into groups, rings, groupoids, and ultimately to category theory, the most abstract of them all. One idle Saturday afternoon I wreaked havoc on the virtual town of Harmony Square, “a green and pleasant place,” according to its founders, famous for its pond swan, living statue, and Pineapple Pizza Festival. Using a fake news site called Megaphone — tagged with the slogan “everything louder than everything else” — and an army of bots, I ginned up outrage and divided the citizenry. In the end, Harmony Square was in shambles.

One idle Saturday afternoon I wreaked havoc on the virtual town of Harmony Square, “a green and pleasant place,” according to its founders, famous for its pond swan, living statue, and Pineapple Pizza Festival. Using a fake news site called Megaphone — tagged with the slogan “everything louder than everything else” — and an army of bots, I ginned up outrage and divided the citizenry. In the end, Harmony Square was in shambles. Akomfrah plays fast and loose with time and place, the real and the constructed, to make larger, more complex narratives. A second three-screen video, Triptych, set in an unnamed location, is a panoply of street portraits. The title is taken from a track by jazz drummer and composer

Akomfrah plays fast and loose with time and place, the real and the constructed, to make larger, more complex narratives. A second three-screen video, Triptych, set in an unnamed location, is a panoply of street portraits. The title is taken from a track by jazz drummer and composer  Barbara Hepworth’s life was by any standard a remarkable one. It was a triumph of determination. She did not come from a deprived background: her father was a civil engineer who became a well-respected county surveyor for the West Riding of Yorkshire. She went to a good school and was exceptionally gifted musically. She wrote with great clarity and was an accomplished draughtswoman. She sailed into Leeds School of Art and in 1921 won a senior scholarship to the Royal College of Art, then under the invigorating leadership of the recently appointed William Rothenstein. At the college, which at the time occupied a building attached to the Victoria and Albert Museum, she chose to concentrate on sculpture, drawing from casts, modelling in clay, carving reliefs in plaster, with some stone and wood carving too. It was a traditional education, undertaken alongside another student from Yorkshire, Henry Moore.

Barbara Hepworth’s life was by any standard a remarkable one. It was a triumph of determination. She did not come from a deprived background: her father was a civil engineer who became a well-respected county surveyor for the West Riding of Yorkshire. She went to a good school and was exceptionally gifted musically. She wrote with great clarity and was an accomplished draughtswoman. She sailed into Leeds School of Art and in 1921 won a senior scholarship to the Royal College of Art, then under the invigorating leadership of the recently appointed William Rothenstein. At the college, which at the time occupied a building attached to the Victoria and Albert Museum, she chose to concentrate on sculpture, drawing from casts, modelling in clay, carving reliefs in plaster, with some stone and wood carving too. It was a traditional education, undertaken alongside another student from Yorkshire, Henry Moore. Few researchers have had the pop culture impact of Suzanne Simard. The University of British Columbia ecologist was the model for Patricia Westerford, a controversial tree scientist in Richard Powers’s 2019 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Overstory. Simard’s work also inspired James Cameron’s vision of the godlike “Tree of Souls” in his 2009 box office hit Avatar. And her research was prominently featured in German forester Peter Wohlleben’s 2016 nonfiction bestseller The Hidden Life of Trees.

Few researchers have had the pop culture impact of Suzanne Simard. The University of British Columbia ecologist was the model for Patricia Westerford, a controversial tree scientist in Richard Powers’s 2019 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Overstory. Simard’s work also inspired James Cameron’s vision of the godlike “Tree of Souls” in his 2009 box office hit Avatar. And her research was prominently featured in German forester Peter Wohlleben’s 2016 nonfiction bestseller The Hidden Life of Trees. Julia, her friends and family agreed, had style. When, out of the blue, the 18-year-old chimpanzee began inserting long, stiff blades of grass into one or both ears and then went about her day with her new statement accessories clearly visible to the world, the other chimpanzees at the Chimfunshi wildlife sanctuary in Zambia were dazzled.

Julia, her friends and family agreed, had style. When, out of the blue, the 18-year-old chimpanzee began inserting long, stiff blades of grass into one or both ears and then went about her day with her new statement accessories clearly visible to the world, the other chimpanzees at the Chimfunshi wildlife sanctuary in Zambia were dazzled. The bag of drugs is sitting untouched on the kitchen bench beside the cans of diced tomatoes and chickpeas I’d earlier quarantined. They – cans not drugs – may be useful, I think, although in less apocalyptic times, I might prefer to soak dried chickpeas to make hummus or chana masala. The chickpea glut follows a 9pm masked assault of Harris Farm Leichhardt and the fact the ex has recently turned up unannounced with a care package of more canned pulses, organic brown rice and greens than I have room to store. An Amma devotee never known to hug spontaneously, he’d stood at the mandated distance of one Kylie Minogue on the other side of my gate (less gateless gate than gate that never shuts properly, the broken latch, I observed as he handed me the box, one of the ten thousand things now unlikely to be repaired…).

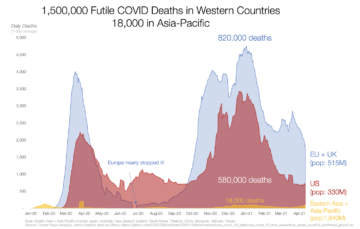

The bag of drugs is sitting untouched on the kitchen bench beside the cans of diced tomatoes and chickpeas I’d earlier quarantined. They – cans not drugs – may be useful, I think, although in less apocalyptic times, I might prefer to soak dried chickpeas to make hummus or chana masala. The chickpea glut follows a 9pm masked assault of Harris Farm Leichhardt and the fact the ex has recently turned up unannounced with a care package of more canned pulses, organic brown rice and greens than I have room to store. An Amma devotee never known to hug spontaneously, he’d stood at the mandated distance of one Kylie Minogue on the other side of my gate (less gateless gate than gate that never shuts properly, the broken latch, I observed as he handed me the box, one of the ten thousand things now unlikely to be repaired…). Soon, over 1.5 million people will have died of COVID in Western countries.

Soon, over 1.5 million people will have died of COVID in Western countries. Niall Ferguson’s new book,

Niall Ferguson’s new book,  It is a truth universally acknowledged—at least by those of the feline persuasion—that an empty box on the floor must be in want of a cat. Ditto for laundry baskets, suitcases, sinks, and even cat carriers (when not used as transport to the vet). This behavior is

It is a truth universally acknowledged—at least by those of the feline persuasion—that an empty box on the floor must be in want of a cat. Ditto for laundry baskets, suitcases, sinks, and even cat carriers (when not used as transport to the vet). This behavior is  The actual problem for India is huge. According to estimates, only 2.2 percent of the current population has been fully vaccinated. India needs 200 to 230 million vaccines a month to vaccinate its 1.5 billion population. Hardly any are available; the much-touted vaccination drive that would make the vaccine available to everyone over eighteen years old lies in disarray. Adar Poonawalla, the CEO of the Serum Institute, has come under fire for undersupply of vaccines and “profiteering” from Covishield, a version of the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine. (India

The actual problem for India is huge. According to estimates, only 2.2 percent of the current population has been fully vaccinated. India needs 200 to 230 million vaccines a month to vaccinate its 1.5 billion population. Hardly any are available; the much-touted vaccination drive that would make the vaccine available to everyone over eighteen years old lies in disarray. Adar Poonawalla, the CEO of the Serum Institute, has come under fire for undersupply of vaccines and “profiteering” from Covishield, a version of the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine. (India