Adam Tooze in Chartbook:

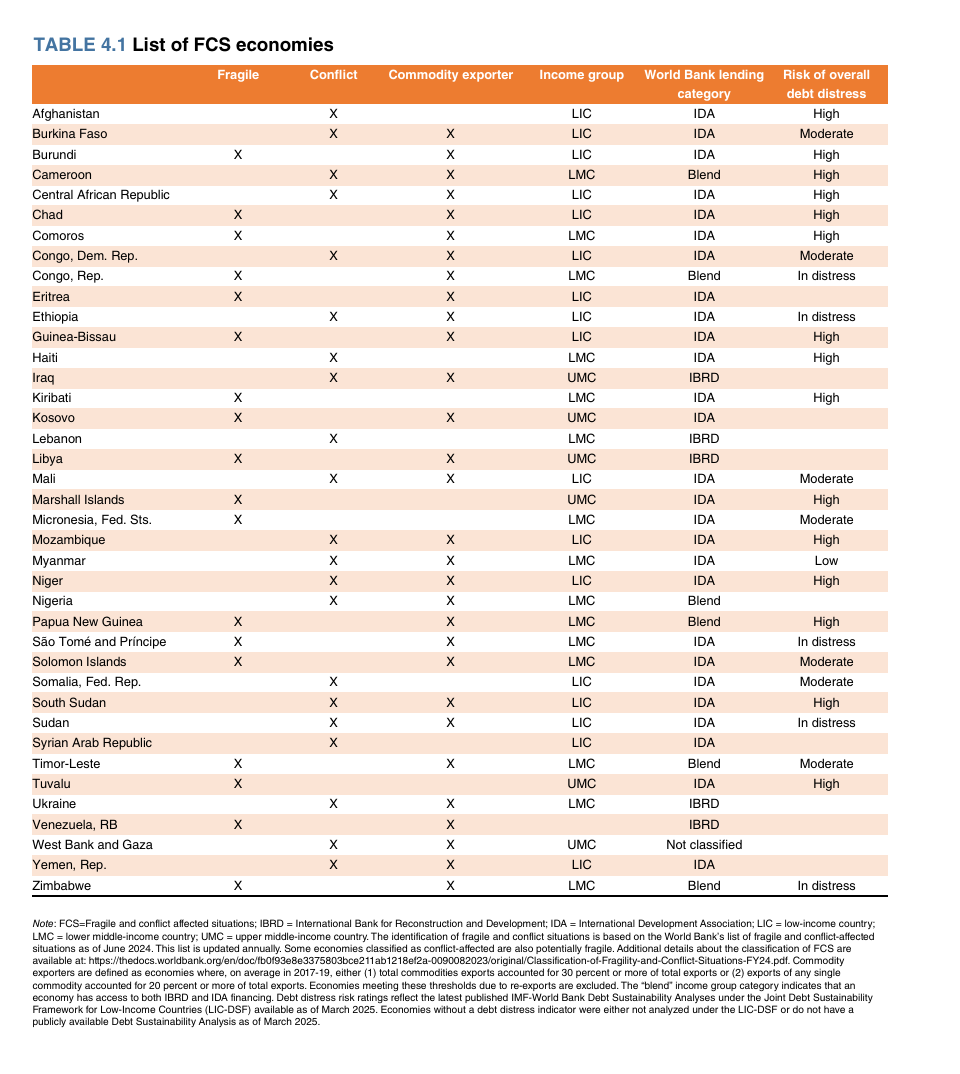

Starting with Gaza and asking where else people starve and fight for their lives is an urgent and productive task. I wrote about the question a few weeks ago. I am prompted to return to it by a new publication by a team at the World Bank.

As I argued in the previous post: Gaza is an extreme case because it involves a rich and powerful state victimizing a tightly controlled and largely defenseless population under a state of siege with the explicit intent of ethnic cleansing in conjunction with an ongoing settler-colonial project. Writing in the 1940s Raphael Lemkin struggled to find categories to describe just such a case in Nazi occupied Poland. The neologism he coined was genocide.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

When I was a girl in the 1950s women, for the most part, got married, gave birth, and stayed home; if necessary, they went to work as schoolteachers or secretaries or salesgirls. They did not enter the professions, start a business, serve in government, or become university professors; nor did they climb a telephone pole, go down in the mines, or compete in a marathon. Today a girl is born with the knowledge that not only can she do any or all of the above, it is even assumed that she will pursue a working life as well as a domestic one. The change in social expectations for women, nothing short of monumental, is due to the Second Wave of American feminism (otherwise known as the Women’s Liberation Movement), a political and social development characterized by the twin efforts of liberals who worked throughout the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s to achieve equality for women under the law and radicals who worked to eradicate deep-dyed, historic sexism through a change in cultural consciousness. Among the leading figures in this second group was Shulamith Firestone, of whom it was said, “I think of her as a shooting star. She flashed brightly across the midnight sky, and then she disappeared.” That’s exactly how I remember her.

When I was a girl in the 1950s women, for the most part, got married, gave birth, and stayed home; if necessary, they went to work as schoolteachers or secretaries or salesgirls. They did not enter the professions, start a business, serve in government, or become university professors; nor did they climb a telephone pole, go down in the mines, or compete in a marathon. Today a girl is born with the knowledge that not only can she do any or all of the above, it is even assumed that she will pursue a working life as well as a domestic one. The change in social expectations for women, nothing short of monumental, is due to the Second Wave of American feminism (otherwise known as the Women’s Liberation Movement), a political and social development characterized by the twin efforts of liberals who worked throughout the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s to achieve equality for women under the law and radicals who worked to eradicate deep-dyed, historic sexism through a change in cultural consciousness. Among the leading figures in this second group was Shulamith Firestone, of whom it was said, “I think of her as a shooting star. She flashed brightly across the midnight sky, and then she disappeared.” That’s exactly how I remember her. ‘I

‘I  When democracy seems everywhere in crisis, it may sound paradoxical, to say the least, that the solution to our troubles is to scrap elections altogether. But that is precisely what political philosopher Alexander Guerrero proposes in his bold and illuminating book, Lottocracy: Democracy Without Elections. We should select political officials not by voting, he contends, but by lottery from among the entire adult citizenry.

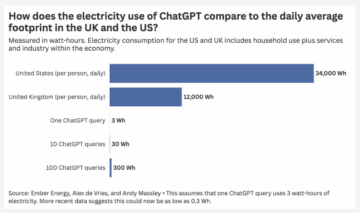

When democracy seems everywhere in crisis, it may sound paradoxical, to say the least, that the solution to our troubles is to scrap elections altogether. But that is precisely what political philosopher Alexander Guerrero proposes in his bold and illuminating book, Lottocracy: Democracy Without Elections. We should select political officials not by voting, he contends, but by lottery from among the entire adult citizenry. My main conclusion is no different from my initial post: individual usage of ChatGPT and other LLMs for most people is a small part of their carbon and energy footprint.

My main conclusion is no different from my initial post: individual usage of ChatGPT and other LLMs for most people is a small part of their carbon and energy footprint. d Antrobus is not the first poet in his family: on his mother’s side, he is descended from Thomas Gray, whose most famous poem, Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1751), is filled with sounds – lowing cows, the droning of a beetle in flight, twittering swallows and a crowing cock among them. These are the noises that, if he’s not wearing hearing aids, might escape Antrobus, who was born with what he often characterises as “missing sound” in the upper and lower registers: a whistling kettle or a doorbell disappears at one end, while at the other, syllables might get elided, rendering, for example, “suspicious” as “spacious” – words with problematically different meanings.

d Antrobus is not the first poet in his family: on his mother’s side, he is descended from Thomas Gray, whose most famous poem, Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1751), is filled with sounds – lowing cows, the droning of a beetle in flight, twittering swallows and a crowing cock among them. These are the noises that, if he’s not wearing hearing aids, might escape Antrobus, who was born with what he often characterises as “missing sound” in the upper and lower registers: a whistling kettle or a doorbell disappears at one end, while at the other, syllables might get elided, rendering, for example, “suspicious” as “spacious” – words with problematically different meanings. Today there are two popular images of Russian society. One, drawn by the Kremlin, presents a people united around the state, supporting the “special military operation,” demanding victory over Ukraine, and proclaiming the advent of a new era and a new world order. The other, deriving from the most radical part of the liberal class, depicts a fragmented and intimidated population mired in cowardly opportunism. Both images allude to totalitarianism, which is characterized by mobilization and atomization, bloodthirstiness and conformism.

Today there are two popular images of Russian society. One, drawn by the Kremlin, presents a people united around the state, supporting the “special military operation,” demanding victory over Ukraine, and proclaiming the advent of a new era and a new world order. The other, deriving from the most radical part of the liberal class, depicts a fragmented and intimidated population mired in cowardly opportunism. Both images allude to totalitarianism, which is characterized by mobilization and atomization, bloodthirstiness and conformism. There are inklings of greatness in Kate Riley’s first novel, “Ruth.” It claims a place on that high modern shelf next to the offbeat books of Ottessa Moshfegh, Sheila Heti, Elif Batuman and Nell Zink — those possessors of wrinkled comic sensibilities rooted in pain.

There are inklings of greatness in Kate Riley’s first novel, “Ruth.” It claims a place on that high modern shelf next to the offbeat books of Ottessa Moshfegh, Sheila Heti, Elif Batuman and Nell Zink — those possessors of wrinkled comic sensibilities rooted in pain. Nicole Spartano does not have diabetes. But the Boston University epidemiologist has occasionally worn a continuous glucose monitor, or CGM, a device once reserved for those with the condition. Her desire to understand how factors such as food, sleep and exercise influence her blood sugar levels stems from her own research into how CGMs might help individuals ward off diseases like diabetes and feel healthier overall. People with diabetes use CGMs to monitor their blood sugar level and need for supplementary insulin, the hormone (produced naturally in most people) that enables cells to consume that sugar for much-needed energy. Less is known, though, about how to interpret CGM readings in people without the condition, Spartano and others say.

Nicole Spartano does not have diabetes. But the Boston University epidemiologist has occasionally worn a continuous glucose monitor, or CGM, a device once reserved for those with the condition. Her desire to understand how factors such as food, sleep and exercise influence her blood sugar levels stems from her own research into how CGMs might help individuals ward off diseases like diabetes and feel healthier overall. People with diabetes use CGMs to monitor their blood sugar level and need for supplementary insulin, the hormone (produced naturally in most people) that enables cells to consume that sugar for much-needed energy. Less is known, though, about how to interpret CGM readings in people without the condition, Spartano and others say. The next manuscript by Indian writer Amitav Ghosh will not be read for 89 years, as he becomes the 12th author to contribute to the

The next manuscript by Indian writer Amitav Ghosh will not be read for 89 years, as he becomes the 12th author to contribute to the  When you think about the long history of life on Earth, you might think, “well, it’s been this progression.” Almost as though it had a direction, almost had a purpose, and that some things are predictable. Not at all. When you really unpack the geological history of the planet and the biological history of the planet, it’s been a random walk through all sorts of events.

When you think about the long history of life on Earth, you might think, “well, it’s been this progression.” Almost as though it had a direction, almost had a purpose, and that some things are predictable. Not at all. When you really unpack the geological history of the planet and the biological history of the planet, it’s been a random walk through all sorts of events.