Kathryn Hughes at The Guardian:

The way Robert Peal describes Georgian England, you’d be mad not to want to live there yourself. In “Merrie Englande” – he uses the term without irony and a fair shot of wistfulness – everyone is high on a trifecta of chocolate, sugar and gin. No one seems cross, although there must have been some almighty hangovers, and sex sounds polymorphous and unproblematic. In the period known as the long 18th century, suggests Peal in his euphoric introduction, you could love any way you chose, get giddy on spirits and dress in a positive rainbow of new colours imported from Britain’s nascent empire. Religion, moreover, was reasonable and unflustered by sin.

The way Robert Peal describes Georgian England, you’d be mad not to want to live there yourself. In “Merrie Englande” – he uses the term without irony and a fair shot of wistfulness – everyone is high on a trifecta of chocolate, sugar and gin. No one seems cross, although there must have been some almighty hangovers, and sex sounds polymorphous and unproblematic. In the period known as the long 18th century, suggests Peal in his euphoric introduction, you could love any way you chose, get giddy on spirits and dress in a positive rainbow of new colours imported from Britain’s nascent empire. Religion, moreover, was reasonable and unflustered by sin.

Peal knows it’s not really like this of course – in the 18th century most people couldn’t afford sugar, homosexuals were hanged and John Wesley founded Methodism in order to make people feel guilty about absolutely everything. Still, Peal’s aim in this avowedly populist book is to rescue the Georgians from collective cultural amnesia.

more here.

Eastman died in 1990, at the age of forty-nine. Ebullient and confrontational in equal measure, he attended the Curtis Institute of Music, joined the Creative Associates program at the University of Buffalo, and found a degree of renown in avant-garde circles. In his final years, struggling with addiction, he faded from view. As a Black gay man, he encountered resistance and incomprehension during his lifetime. He is now experiencing a dizzying posthumous renaissance, to the point where his Symphony No. II is scheduled for the New York Philharmonic’s 2021-22 season.

Eastman died in 1990, at the age of forty-nine. Ebullient and confrontational in equal measure, he attended the Curtis Institute of Music, joined the Creative Associates program at the University of Buffalo, and found a degree of renown in avant-garde circles. In his final years, struggling with addiction, he faded from view. As a Black gay man, he encountered resistance and incomprehension during his lifetime. He is now experiencing a dizzying posthumous renaissance, to the point where his Symphony No. II is scheduled for the New York Philharmonic’s 2021-22 season. The United States is not in the midst of a “culture war” over race and racism. The animating force of our current conflict is not our differing values, beliefs, moral codes, or practices. The American people aren’t divided. The American people are being divided. Republican operatives have

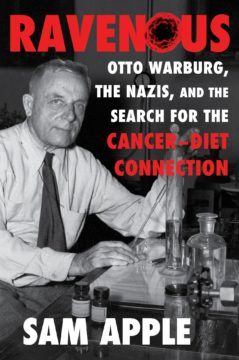

The United States is not in the midst of a “culture war” over race and racism. The animating force of our current conflict is not our differing values, beliefs, moral codes, or practices. The American people aren’t divided. The American people are being divided. Republican operatives have  When the Nazis seized power in March 1933, it was not unusual for major scientific institutes to be led by Nobel laureates with Jewish roots: Albert Einstein and Otto Meyerhof, both Jewish, ran prestigious centers of physics and medical research; Fritz Haber, who’d converted from Judaism in the late 19th century, ran a chemistry institute; and Otto Warburg, who was raised as a Protestant but had two Jewish grandparents, was the director of a recently opened center for cell physiology.

When the Nazis seized power in March 1933, it was not unusual for major scientific institutes to be led by Nobel laureates with Jewish roots: Albert Einstein and Otto Meyerhof, both Jewish, ran prestigious centers of physics and medical research; Fritz Haber, who’d converted from Judaism in the late 19th century, ran a chemistry institute; and Otto Warburg, who was raised as a Protestant but had two Jewish grandparents, was the director of a recently opened center for cell physiology. When critics write at length about the critics they admire, look out for self-portraiture. In a 2008 New Yorker essay, the critic and intellectual historian Louis Menand explored Lionel Trilling’s influence on the postwar era, during which Trilling was America’s preeminent literary critic and among its weightiest public intellectuals. One of the few aspects of Trilling’s career about which Menand had major reservations was the unfinished second novel Trilling began shortly after publishing his first, The Middle of the Journey, but abandoned about a third of the way through. This work, Menand found, “doesn’t have much literary interest, but it does have a lot of biographical interest, because it lets us see Trilling imagining his own world—the world of ambitious young critics, resentful middle-aged professors, pompous publishers and compromised foundation heads, intellectual femmes fatales, and the megalomaniacal editors of little magazines—as a nineteenth-century novel.”

When critics write at length about the critics they admire, look out for self-portraiture. In a 2008 New Yorker essay, the critic and intellectual historian Louis Menand explored Lionel Trilling’s influence on the postwar era, during which Trilling was America’s preeminent literary critic and among its weightiest public intellectuals. One of the few aspects of Trilling’s career about which Menand had major reservations was the unfinished second novel Trilling began shortly after publishing his first, The Middle of the Journey, but abandoned about a third of the way through. This work, Menand found, “doesn’t have much literary interest, but it does have a lot of biographical interest, because it lets us see Trilling imagining his own world—the world of ambitious young critics, resentful middle-aged professors, pompous publishers and compromised foundation heads, intellectual femmes fatales, and the megalomaniacal editors of little magazines—as a nineteenth-century novel.” Einstein completed his Ph.D. thesis in 1905 with Professor

Einstein completed his Ph.D. thesis in 1905 with Professor  Not too many 38-years-olds deserve their own biography, let alone two. But ever since Kim Jong Un became the third ruler of North Korea in 2011, he has fascinated the American media. A Seth Rogen movie, The New Yorker covers, and South Park cartoons have all made Kim — and his haircut — the target of much lampooning. And in one of the strangest twists in recent international diplomacy, Donald Trump caused a sensation by announcing the two “fell in love” with each other. All this publicity has ultimately resulted in a cartoonish version of Kim, which, however good for a chuckle, obscures how this enigmatic dictator and his family have ruled over the course of three generations.

Not too many 38-years-olds deserve their own biography, let alone two. But ever since Kim Jong Un became the third ruler of North Korea in 2011, he has fascinated the American media. A Seth Rogen movie, The New Yorker covers, and South Park cartoons have all made Kim — and his haircut — the target of much lampooning. And in one of the strangest twists in recent international diplomacy, Donald Trump caused a sensation by announcing the two “fell in love” with each other. All this publicity has ultimately resulted in a cartoonish version of Kim, which, however good for a chuckle, obscures how this enigmatic dictator and his family have ruled over the course of three generations. There is also a kind of ostentatious world-weariness in his writings that can be oddly enchanting. In one sense, his thought is burdened by that deep historical consciousness that seems to be the peculiar vocation of continental philosophy in its long post-Hegelian twilight. As a result, he possesses too keen a hermeneutical awareness of the fluidity, ambiguity, and cultural contingency of philosophy’s terms and concepts to mistake them for invariable properties that can be absorbed into some timeless propositional calculus in the way so much of Anglo-American philosophy imagines it can. But, in another sense, it is precisely this “burden” of historical consciousness that imparts a paradoxical levity to his project. Many of his books feel like expeditions in search of secrets from the past: forgotten cultural ancestries, effaced spiritual monuments, occult currents within the flow of social evolution. Whether one admires or deplores his thought—or has a distinctly mixed opinion of it, as I do—no one could plausibly claim that it is dull.

There is also a kind of ostentatious world-weariness in his writings that can be oddly enchanting. In one sense, his thought is burdened by that deep historical consciousness that seems to be the peculiar vocation of continental philosophy in its long post-Hegelian twilight. As a result, he possesses too keen a hermeneutical awareness of the fluidity, ambiguity, and cultural contingency of philosophy’s terms and concepts to mistake them for invariable properties that can be absorbed into some timeless propositional calculus in the way so much of Anglo-American philosophy imagines it can. But, in another sense, it is precisely this “burden” of historical consciousness that imparts a paradoxical levity to his project. Many of his books feel like expeditions in search of secrets from the past: forgotten cultural ancestries, effaced spiritual monuments, occult currents within the flow of social evolution. Whether one admires or deplores his thought—or has a distinctly mixed opinion of it, as I do—no one could plausibly claim that it is dull. Weil’s essential contribution to the theory of complaint comes by way of her distinction between ordinary suffering and something she calls “affliction.” Suffering is pain one can bear, pain that does not imprint itself on the soul. Sometimes, we even choose suffering, as in strenuous exercise, unmedicated childbirth or getting one’s ears pierced. Getting beat up in an alleyway by strangers is not like any of those forms of suffering. A violent attack, even one that does minimum physical damage, hurts in a distinctive way—in a way that, as Weil would put it, raises a question.

Weil’s essential contribution to the theory of complaint comes by way of her distinction between ordinary suffering and something she calls “affliction.” Suffering is pain one can bear, pain that does not imprint itself on the soul. Sometimes, we even choose suffering, as in strenuous exercise, unmedicated childbirth or getting one’s ears pierced. Getting beat up in an alleyway by strangers is not like any of those forms of suffering. A violent attack, even one that does minimum physical damage, hurts in a distinctive way—in a way that, as Weil would put it, raises a question. The duration of felt experience is between two and three seconds—about as long as it takes, the psychologist Marc Wittmann points out, for Paul McCartney to sing the words “Hey Jude.” Everything before belongs to memory; everything after is anticipation. It’s a strange, barely fathomable fact that our lives are lived through this small, moving window. Practitioners of mindfulness meditation often strive to rest their consciousness within it. The rest of us might encounter something similar during certain present-tense moments—perhaps while rock climbing, improvising music, making love. Being in the moment is said to be a perk of sadomasochism; as a devotee of B.D.S.M. once explained, “A whip is a great way to get someone to be here now. They can’t look away from it, and they can’t think about anything else!”

The duration of felt experience is between two and three seconds—about as long as it takes, the psychologist Marc Wittmann points out, for Paul McCartney to sing the words “Hey Jude.” Everything before belongs to memory; everything after is anticipation. It’s a strange, barely fathomable fact that our lives are lived through this small, moving window. Practitioners of mindfulness meditation often strive to rest their consciousness within it. The rest of us might encounter something similar during certain present-tense moments—perhaps while rock climbing, improvising music, making love. Being in the moment is said to be a perk of sadomasochism; as a devotee of B.D.S.M. once explained, “A whip is a great way to get someone to be here now. They can’t look away from it, and they can’t think about anything else!” Two compendiums of data unite genetic profiling with drug testing to create the most complete picture yet of how mutations can shape a cancer’s response to therapy. The results, published today in Nature

Two compendiums of data unite genetic profiling with drug testing to create the most complete picture yet of how mutations can shape a cancer’s response to therapy. The results, published today in Nature After her first novel, The God of Small Things (1997), Arundhati Roy did not publish another for twenty years, when The Ministry of Utmost Happiness was released in 2017. The intervening decades were nonetheless filled with writing: essays on dams, displacement, and democracy, which appeared in newspapers and magazines such as Outlook, Frontline, and the Guardian, and were collected in volumes that quickly came to outnumber the novels. Most of these essays were compiled in 2019 in My Seditious Heart, which, with footnotes, comes to nearly a thousand pages; less than a year later she published nine new essays in Azadi.

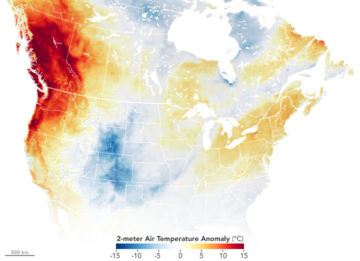

After her first novel, The God of Small Things (1997), Arundhati Roy did not publish another for twenty years, when The Ministry of Utmost Happiness was released in 2017. The intervening decades were nonetheless filled with writing: essays on dams, displacement, and democracy, which appeared in newspapers and magazines such as Outlook, Frontline, and the Guardian, and were collected in volumes that quickly came to outnumber the novels. Most of these essays were compiled in 2019 in My Seditious Heart, which, with footnotes, comes to nearly a thousand pages; less than a year later she published nine new essays in Azadi. The last week of June saw shocking temperatures in Oregon, Washington state, and British Columbia. Differentiating a forecast in Canada from a forecast in Phoenix is usually a breeze, but not in June. All-time high-temperature records—not just daily records—were smashed across the region. Portland International Airport broke its all-time record of 41.7°C (107°F) by a whopping 5°C (9°F). The small town of Lytton set a new record high for the entire country of Canada at 49.6°C (121.3°F) on June 29. In the days that followed,

The last week of June saw shocking temperatures in Oregon, Washington state, and British Columbia. Differentiating a forecast in Canada from a forecast in Phoenix is usually a breeze, but not in June. All-time high-temperature records—not just daily records—were smashed across the region. Portland International Airport broke its all-time record of 41.7°C (107°F) by a whopping 5°C (9°F). The small town of Lytton set a new record high for the entire country of Canada at 49.6°C (121.3°F) on June 29. In the days that followed,  This is how capitalism ends: not with a revolutionary bang, but with an evolutionary whimper. Just as it displaced feudalism gradually, surreptitiously, until one day the bulk of human relations were market-based and feudalism was swept away, so capitalism today is being toppled by a new economic mode: techno-feudalism.

This is how capitalism ends: not with a revolutionary bang, but with an evolutionary whimper. Just as it displaced feudalism gradually, surreptitiously, until one day the bulk of human relations were market-based and feudalism was swept away, so capitalism today is being toppled by a new economic mode: techno-feudalism.