Shaan Sachdev over at the LA Review of Books:

Shaan Sachdev over at the LA Review of Books:

A FEW YEARS AGO, I trekked, biked, and rode trains and buses through Weimar, Frankfurt, Heidelberg, Stuttgart, Freiburg, Todtnauberg, Basel, and, finally, Sils Maria. I was in Germany and Switzerland, with a servile sort of eros, to gape and touch and stroll through the universities and apartments at which some of our grandest modern philosophers had once lived: Goethe, Hegel, Husserl, Schopenhauer, Heidegger, Nietzsche, Jaspers, and Arendt. Locals and students expressed little surprise when they learned I was poking around the Hegel Haus or peeking inside classrooms at Freiburg where Edmund Husserl taught phenomenology. The manager of a prim restaurant inside Todtnauberg’s nicest hotel excitedly interrupted my dinner of white fish and potatoes to show me the photographs on his office walls of his father together with Martin Heidegger; then he poured me a few glasses of Spätburgunder on the house.

Curiously, the only name of the lot that elicited more confusion than ratification — also the only woman and the only one to have persistently rebuffed the ascription of “philosopher” — was Hannah Arendt. There was less consensus about her legacy and allure. “Why her?” asked a young woman at the University of Freiburg who had spiritedly agreed to sneak me into Kollegiengebäude I, which hosted the philology, theology, and philosophy departments. “Was she one of the greats?”

More here.

Branko Milanovic over at his substack:

Branko Milanovic over at his substack: Kim Phillips-Fein in The New Republic:

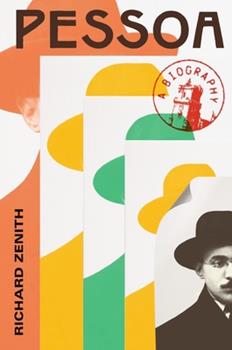

Kim Phillips-Fein in The New Republic: Three heteronyms in particular enabled Pessoa to work through the history of poetry. Impersonating a simple shepherd called Alberto Caeiro, he wrote naive pastoral lyrics; as the refined classicist Ricardo Reis, he composed Latinate homages to the gods; giving voice to the futurist Álvaro de Campos, supposedly an engineer by trade, he celebrated mechanised urban modernity. Commuting between these aliases was like metempsychosis or perhaps, as Pessoa confessed to a critic, like changing sex. His alter egos had extra-literary uses too. To extricate himself from a flirtation with a clingy young woman, Pessoa made Campos write a letter warning her off and when she telephoned in the hope of making a date he answered the call as Reis and informed her that Fernando was not available.

Three heteronyms in particular enabled Pessoa to work through the history of poetry. Impersonating a simple shepherd called Alberto Caeiro, he wrote naive pastoral lyrics; as the refined classicist Ricardo Reis, he composed Latinate homages to the gods; giving voice to the futurist Álvaro de Campos, supposedly an engineer by trade, he celebrated mechanised urban modernity. Commuting between these aliases was like metempsychosis or perhaps, as Pessoa confessed to a critic, like changing sex. His alter egos had extra-literary uses too. To extricate himself from a flirtation with a clingy young woman, Pessoa made Campos write a letter warning her off and when she telephoned in the hope of making a date he answered the call as Reis and informed her that Fernando was not available. The title of Rebecca Donner’s astonishing new book is a line by Goethe, from a volume of his poems that had been smuggled into the cell of Mildred Harnack — an American woman who was shackled in a Berlin prison, awaiting her death sentence by the Nazi regime. On Feb. 16, 1943, the day she would be taken to the execution shed and beheaded, a chaplain found Mildred hunched over the poems, scribbling in the margins. The heavy gothic font of the German original was accompanied by the ghostly script of her English translation, written with a pencil stub.

The title of Rebecca Donner’s astonishing new book is a line by Goethe, from a volume of his poems that had been smuggled into the cell of Mildred Harnack — an American woman who was shackled in a Berlin prison, awaiting her death sentence by the Nazi regime. On Feb. 16, 1943, the day she would be taken to the execution shed and beheaded, a chaplain found Mildred hunched over the poems, scribbling in the margins. The heavy gothic font of the German original was accompanied by the ghostly script of her English translation, written with a pencil stub. T

T O

O The better machines become at transferring equivalent words and even almost correct syntax and grammatical structures from one language to another, the more the mechanics of translation matter less, and the more we are aware of inflections and innuendoes; what we don’t know what to call, we call beauty.

The better machines become at transferring equivalent words and even almost correct syntax and grammatical structures from one language to another, the more the mechanics of translation matter less, and the more we are aware of inflections and innuendoes; what we don’t know what to call, we call beauty. Vaclav Smil is my favorite author, but I sometimes hesitate to recommend his books to other people. His writing, while brilliant, is often too detailed or obscure for a general audience. (Deep dives on

Vaclav Smil is my favorite author, but I sometimes hesitate to recommend his books to other people. His writing, while brilliant, is often too detailed or obscure for a general audience. (Deep dives on  The shift in Washington is undeniable: the Middle East is no longer a top priority for the United States. The U.S. withdrawal from the broader region is evident in the departure of troops from Afghanistan and reductions in U.S. military commitments to Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia, alongside a heightened focus on China and Russia. There are good reasons for this shift in strategy, especially given the woeful recent history of U.S. involvement in the region, but it also brings risks of its own. The United States’ precipitous departure from Iraq in 2011, for example, paved the way for the rise of the Islamic State (also known as ISIS) and the expansion of Iran’s regional footprint. To avert similar damage this time, Washington must find a way to pair reductions in military commitments with gains in regional stability. One of the best opportunities for achieving those gains lies in emerging talks between the region’s two most consequential antagonists: Iran and Saudi Arabia.

The shift in Washington is undeniable: the Middle East is no longer a top priority for the United States. The U.S. withdrawal from the broader region is evident in the departure of troops from Afghanistan and reductions in U.S. military commitments to Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia, alongside a heightened focus on China and Russia. There are good reasons for this shift in strategy, especially given the woeful recent history of U.S. involvement in the region, but it also brings risks of its own. The United States’ precipitous departure from Iraq in 2011, for example, paved the way for the rise of the Islamic State (also known as ISIS) and the expansion of Iran’s regional footprint. To avert similar damage this time, Washington must find a way to pair reductions in military commitments with gains in regional stability. One of the best opportunities for achieving those gains lies in emerging talks between the region’s two most consequential antagonists: Iran and Saudi Arabia. Pessoa has a telling line in his sequence of poems “Slanting Rain” that provides a good way of approaching this: “I don’t know who I dream I am.” Zenith doesn’t reference it, yet I’ve always thought the quotation succinctly gets at the impetus behind Pessoa’s use of heteronyms, among them his three principal and stylistically distinct poetry-writing pseudoselves: Alvaro de Campos (a naval engineer by trade with a lyrical bent), Alberto Caeiro (a rustic and believer in the essence of nature), and Ricardo Reis (a doctor who produced philosophical Horatian odes). And, true, in the poetry there is often the dreamlike element of being “the other,” a ghostly, untethered feeling marked by searingly honest searching.

Pessoa has a telling line in his sequence of poems “Slanting Rain” that provides a good way of approaching this: “I don’t know who I dream I am.” Zenith doesn’t reference it, yet I’ve always thought the quotation succinctly gets at the impetus behind Pessoa’s use of heteronyms, among them his three principal and stylistically distinct poetry-writing pseudoselves: Alvaro de Campos (a naval engineer by trade with a lyrical bent), Alberto Caeiro (a rustic and believer in the essence of nature), and Ricardo Reis (a doctor who produced philosophical Horatian odes). And, true, in the poetry there is often the dreamlike element of being “the other,” a ghostly, untethered feeling marked by searingly honest searching. The economic machine is breaking down, retail businesses are almost bankrupt, and yet the city has been seized by a frenzy of activity since this morning, just like in the glory days of its suddenly vanished opulence. The gridlock is no worse than it was back then, even though the traffic lights are out because of the electricity shortages. And where the lights are actually working, police officers are controlling traffic and encouraging drivers to ignore them, directing everyone to move at the same time with grand, raging gestures, as if they were vengefully making a point of reminding us that order no longer reigns, so why should anyone even bother respecting these last damned surviving traffic lights. The drivers are astonished. Some, like me, resist, under the officers’ resentful eyes. They seem aware and ashamed that they have become representatives of the general chaos and the failure of the state, and are going above and beyond what’s actually necessary, as if they were furiously smashing a prized object to pieces to punish themselves for having carelessly chipped it. I talked to my wife about this when I got home, she didn’t seem to care about the feelings I was ascribing to the traffic officers. She doesn’t like them and even before the economic crisis she thought that they actually tend to be the cause of the gridlock rather than anything else, that they always complicate any situation they are in, that city traffic is like a natural process, it always ends up regulating itself, and that human intervention only disturbs it and makes it more complicated.

The economic machine is breaking down, retail businesses are almost bankrupt, and yet the city has been seized by a frenzy of activity since this morning, just like in the glory days of its suddenly vanished opulence. The gridlock is no worse than it was back then, even though the traffic lights are out because of the electricity shortages. And where the lights are actually working, police officers are controlling traffic and encouraging drivers to ignore them, directing everyone to move at the same time with grand, raging gestures, as if they were vengefully making a point of reminding us that order no longer reigns, so why should anyone even bother respecting these last damned surviving traffic lights. The drivers are astonished. Some, like me, resist, under the officers’ resentful eyes. They seem aware and ashamed that they have become representatives of the general chaos and the failure of the state, and are going above and beyond what’s actually necessary, as if they were furiously smashing a prized object to pieces to punish themselves for having carelessly chipped it. I talked to my wife about this when I got home, she didn’t seem to care about the feelings I was ascribing to the traffic officers. She doesn’t like them and even before the economic crisis she thought that they actually tend to be the cause of the gridlock rather than anything else, that they always complicate any situation they are in, that city traffic is like a natural process, it always ends up regulating itself, and that human intervention only disturbs it and makes it more complicated. Steven Weinberg

Steven Weinberg It was tempting to dismiss the show unfolding inside the Dream City Church in Phoenix, Arizona, as an unintended comedy. One night in June, a few hundred people gathered for the première of “The Deep Rig,” a film financed by the multimillionaire founder of Overstock.com,

It was tempting to dismiss the show unfolding inside the Dream City Church in Phoenix, Arizona, as an unintended comedy. One night in June, a few hundred people gathered for the première of “The Deep Rig,” a film financed by the multimillionaire founder of Overstock.com,