Joan Didion at The New Yorker:

The message Martha is actually sending, the reason large numbers of American women count watching her a comforting and obscurely inspirational experience, seems not very well understood. There has been a flurry of academic work done on the cultural meaning of her success (in the summer of 1998, the New York Times reported that “about two dozen scholars across the United States and Canada” were producing such studies as “A Look at Linen Closets: Liminality, Structure and Anti-Structure in Martha Stewart Living” and locating “the fear of transgression” in the magazine’s “recurrent images of fences, hedges and garden walls”), but there remains, both in the bond she makes and in the outrage she provokes, something unaddressed, something pitched, like a dog whistle, too high for traditional textual analysis. The outrage, which reaches sometimes startling levels, centers on the misconception that she has somehow tricked her admirers into not noticing the ambition that brought her to their attention. To her critics, she seems to represent a fraud to be exposed, a wrong to be righted. “She’s a shark,” one declares in Salon. “However much she’s got, Martha wants more. And she wants it her way and in her world, not in the balls-out boys’ club realms of real estate or technology, but in the delicate land of doily hearts and wedding cakes.”

The message Martha is actually sending, the reason large numbers of American women count watching her a comforting and obscurely inspirational experience, seems not very well understood. There has been a flurry of academic work done on the cultural meaning of her success (in the summer of 1998, the New York Times reported that “about two dozen scholars across the United States and Canada” were producing such studies as “A Look at Linen Closets: Liminality, Structure and Anti-Structure in Martha Stewart Living” and locating “the fear of transgression” in the magazine’s “recurrent images of fences, hedges and garden walls”), but there remains, both in the bond she makes and in the outrage she provokes, something unaddressed, something pitched, like a dog whistle, too high for traditional textual analysis. The outrage, which reaches sometimes startling levels, centers on the misconception that she has somehow tricked her admirers into not noticing the ambition that brought her to their attention. To her critics, she seems to represent a fraud to be exposed, a wrong to be righted. “She’s a shark,” one declares in Salon. “However much she’s got, Martha wants more. And she wants it her way and in her world, not in the balls-out boys’ club realms of real estate or technology, but in the delicate land of doily hearts and wedding cakes.”

more here.

Vaccines don’t last forever. This is by design: Like many of the microbes they mimic, the contents of the shots stick around only as long as it takes the body to eliminate them, a tenure on the order of

Vaccines don’t last forever. This is by design: Like many of the microbes they mimic, the contents of the shots stick around only as long as it takes the body to eliminate them, a tenure on the order of  In the spring of 1880, in the midst of what felt like a political tipping point, a new monument dedicated to the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin was unveiled in Moscow. Alexander II’s Great Reforms of the 1860s — including the emancipation of the serfs — had not satisfied the appetites of radicals for change. Most alarming to moderate Russians were the women who had begun joining the ranks of the self-described Nihilists. They smoked cigarettes, cut their hair short, preferred Feuerbach to romance novels and spurned marriage in favor of careers in science and medicine (or, occasionally, terrorism).

In the spring of 1880, in the midst of what felt like a political tipping point, a new monument dedicated to the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin was unveiled in Moscow. Alexander II’s Great Reforms of the 1860s — including the emancipation of the serfs — had not satisfied the appetites of radicals for change. Most alarming to moderate Russians were the women who had begun joining the ranks of the self-described Nihilists. They smoked cigarettes, cut their hair short, preferred Feuerbach to romance novels and spurned marriage in favor of careers in science and medicine (or, occasionally, terrorism). Amitava Kumar tends to talk about his forthcoming novel,

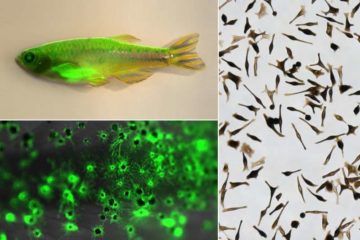

Amitava Kumar tends to talk about his forthcoming novel,  While the explosion in food allergies is well documented, there is no agreement on why it’s happened. Theories abound: one of the most enduring has been the so-called “hygiene hypothesis,” put forward by the epidemiologist David Strachan in 1989, which suggested that modern society’s obsession with cleanliness was at the root of the problem. The hypothesis proposed that a lack of exposure to dirt and bugs leads to a badly calibrated immune system prone to misfires. But though the idea feels intuitive, and has thus found a willing public audience, evidence for it has been lacking. Scientists now say that over-enthusiastic hygiene practices are unlikely to be the cause, although exposure to the lungs of particular cleaning products might be.

While the explosion in food allergies is well documented, there is no agreement on why it’s happened. Theories abound: one of the most enduring has been the so-called “hygiene hypothesis,” put forward by the epidemiologist David Strachan in 1989, which suggested that modern society’s obsession with cleanliness was at the root of the problem. The hypothesis proposed that a lack of exposure to dirt and bugs leads to a badly calibrated immune system prone to misfires. But though the idea feels intuitive, and has thus found a willing public audience, evidence for it has been lacking. Scientists now say that over-enthusiastic hygiene practices are unlikely to be the cause, although exposure to the lungs of particular cleaning products might be. On February 9, 1967, hours after the US Air Force pounded Haiphong Harbor and several Vietnamese airfields, NBC television screened a politically momentous episode of Star Trek. Entitled “

On February 9, 1967, hours after the US Air Force pounded Haiphong Harbor and several Vietnamese airfields, NBC television screened a politically momentous episode of Star Trek. Entitled “ The fifteenth-century Italian artist Fra Angelico invented emotional interiority in art; laid the stylistic groundwork for Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Mark Rothko; and theorized a utopian world, one in which everything and everyone is ultimately linked.

The fifteenth-century Italian artist Fra Angelico invented emotional interiority in art; laid the stylistic groundwork for Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Mark Rothko; and theorized a utopian world, one in which everything and everyone is ultimately linked. A botanist’s quest for new medicines takes her deep into the Amazon. A computer scientist and a sci-fi author peer into the future of artificial intelligence. An anthropologist confronts changing attitudes about death. From an ambitious road map for the future of physics to a whirlwind tour of animal outlaws, the books on this year’s fall reading list—reviewed by alumni of the AAAS Science and Technology Policy Fellowship program—challenge readers to see the topics under consideration in a new light. Join a neurologist on a journey to understand the myriad causes of psychogenic illnesses, gain a better grasp of the origins of the climate crisis, and confront the ways ideas about gender have shaped innovation, all with the help of the books reviewed below. —Valerie Thompson

A botanist’s quest for new medicines takes her deep into the Amazon. A computer scientist and a sci-fi author peer into the future of artificial intelligence. An anthropologist confronts changing attitudes about death. From an ambitious road map for the future of physics to a whirlwind tour of animal outlaws, the books on this year’s fall reading list—reviewed by alumni of the AAAS Science and Technology Policy Fellowship program—challenge readers to see the topics under consideration in a new light. Join a neurologist on a journey to understand the myriad causes of psychogenic illnesses, gain a better grasp of the origins of the climate crisis, and confront the ways ideas about gender have shaped innovation, all with the help of the books reviewed below. —Valerie Thompson In his 1591 treatise De monade, numero et figura liber (On the Monad, Number, and Figure), Bruno described three types of monads: God, souls, and atoms. Much later, the concept of the monad was popularized by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. In Leibniz’s system, monads are the basic, irreducible components of the universe. Each monad is a unique, indestructible soul-like entity. Monads cannot interact, but all are perfectly synchronized with one another by God.

In his 1591 treatise De monade, numero et figura liber (On the Monad, Number, and Figure), Bruno described three types of monads: God, souls, and atoms. Much later, the concept of the monad was popularized by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. In Leibniz’s system, monads are the basic, irreducible components of the universe. Each monad is a unique, indestructible soul-like entity. Monads cannot interact, but all are perfectly synchronized with one another by God. February, 1991. The first night on the ship, I wore a cobalt velvet jacket with a shawl collar, stonewashed jeans, and a necklace bearing three tiers of iridescent orbs, an unintentional nod to the disco ball that would cast the ballroom in a glittering glow. I was barely a teen-ager, and, from my view across the dining room, I appeared to be the sole female passenger on the cruise ship carrying several hundred gay men from Miami, Florida, to San Juan, Puerto Rico, over the course of seven days—and definitely the only kid. I was travelling with my father, who, less than eighteen months later, would die after a five-year battle with aids. But, for the moment, he was well—at least well enough to take his daughter on a Caribbean vacation.

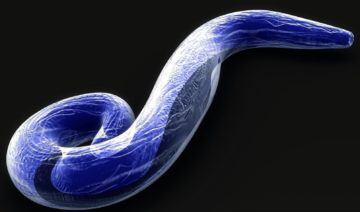

February, 1991. The first night on the ship, I wore a cobalt velvet jacket with a shawl collar, stonewashed jeans, and a necklace bearing three tiers of iridescent orbs, an unintentional nod to the disco ball that would cast the ballroom in a glittering glow. I was barely a teen-ager, and, from my view across the dining room, I appeared to be the sole female passenger on the cruise ship carrying several hundred gay men from Miami, Florida, to San Juan, Puerto Rico, over the course of seven days—and definitely the only kid. I was travelling with my father, who, less than eighteen months later, would die after a five-year battle with aids. But, for the moment, he was well—at least well enough to take his daughter on a Caribbean vacation. Memes become omnipresent for a variety of reasons. They might be fodder for entertaining video footage. They might provide a tool for people to express themselves, or cater to deep-seated hopes or anxieties. Ivermectin, which is used for some human applications as well as horse deworming, answered the desire for a covid miracle cure in the face of the United States’ recent surge in

Memes become omnipresent for a variety of reasons. They might be fodder for entertaining video footage. They might provide a tool for people to express themselves, or cater to deep-seated hopes or anxieties. Ivermectin, which is used for some human applications as well as horse deworming, answered the desire for a covid miracle cure in the face of the United States’ recent surge in  Right now, in your body, lurk thousands of cells with DNA mistakes that could cause cancer. Yet only in rare instances do these DNA mistakes, called genetic mutations, lead to a full-blown cancer. Why? The standard explanation is that it takes a certain number of genetic “hits” to a cell’s DNA to push a cell over the edge. But there are well-known cases in which the same set of mutations clearly causes cancer in one context, but not in another. A good example is a mole. The cells making up a mole are genetically abnormal. Quite often, they contain a mutated DNA version of the BRAF gene that, when found in cells located outside of a mole, will often lead to melanoma. But the vast majority of moles will never turn cancerous. It’s a conundrum that has scientists looking to cellular context for clues to explain the difference.

Right now, in your body, lurk thousands of cells with DNA mistakes that could cause cancer. Yet only in rare instances do these DNA mistakes, called genetic mutations, lead to a full-blown cancer. Why? The standard explanation is that it takes a certain number of genetic “hits” to a cell’s DNA to push a cell over the edge. But there are well-known cases in which the same set of mutations clearly causes cancer in one context, but not in another. A good example is a mole. The cells making up a mole are genetically abnormal. Quite often, they contain a mutated DNA version of the BRAF gene that, when found in cells located outside of a mole, will often lead to melanoma. But the vast majority of moles will never turn cancerous. It’s a conundrum that has scientists looking to cellular context for clues to explain the difference. I AM ON MY FOURTH HURRICANE

I AM ON MY FOURTH HURRICANE I know that many liberals, and not a few leftists, will dismiss this account as wildly hyperbolic. Liberals have an abiding faith in the solidity of American democratic institutions; leftists have internally consistent arguments demonstrating why a putsch can’t happen because it wouldn’t be in capital’s interests. It always seems most reasonable to project the future as a straight-line extrapolation from the recent past and present; inertia and path dependence are powerful forces. But that’s why political scientists nearly all were caught flat-footed by the collapse of the Soviet Union. To be clear, I’m not predicting the possible outcome I’ve laid out. My objective is to indicate dangerous, opportunistic tendencies and dynamics at work in this political moment which I think liberals and whatever counts as a left in the United States have been underestimating or, worse, dismissing entirely. If forced to bet, based on the perspective on American political history since 1980, or even 1964, that I’ve laid out here, I’d speculate that the nightmare outline I’ve sketched is between possible and likely, I imagine and hope closer to the former than the latter.

I know that many liberals, and not a few leftists, will dismiss this account as wildly hyperbolic. Liberals have an abiding faith in the solidity of American democratic institutions; leftists have internally consistent arguments demonstrating why a putsch can’t happen because it wouldn’t be in capital’s interests. It always seems most reasonable to project the future as a straight-line extrapolation from the recent past and present; inertia and path dependence are powerful forces. But that’s why political scientists nearly all were caught flat-footed by the collapse of the Soviet Union. To be clear, I’m not predicting the possible outcome I’ve laid out. My objective is to indicate dangerous, opportunistic tendencies and dynamics at work in this political moment which I think liberals and whatever counts as a left in the United States have been underestimating or, worse, dismissing entirely. If forced to bet, based on the perspective on American political history since 1980, or even 1964, that I’ve laid out here, I’d speculate that the nightmare outline I’ve sketched is between possible and likely, I imagine and hope closer to the former than the latter. At the end of June, the World Health Organization certified China as having eliminated malaria. The announcement may have gotten a little drowned out by the mass spectacles surrounding the Communist Party’s 100th birthday, but make no mistake: going from 30 million cases annually to zero really is a reason to be cheerful.

At the end of June, the World Health Organization certified China as having eliminated malaria. The announcement may have gotten a little drowned out by the mass spectacles surrounding the Communist Party’s 100th birthday, but make no mistake: going from 30 million cases annually to zero really is a reason to be cheerful.