Anne Applebaum in The Atlantic:

“It was no great distance, in those days, from the prison-door to the market-place. Measured by the prisoner’s experience, however, it might be reckoned a journey of some length.”

“It was no great distance, in those days, from the prison-door to the market-place. Measured by the prisoner’s experience, however, it might be reckoned a journey of some length.”

So begins the tale of Hester Prynne, as recounted in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s most famous novel, The Scarlet Letter. As readers of this classic American text know, the story begins after Hester gives birth to a child out of wedlock and refuses to name the father. As a result, she is sentenced to be mocked by a jeering crowd, undergoing “an agony from every footstep of those that thronged to see her, as if her heart had been flung into the street for them all to spurn and trample upon.” After that, she must wear a scarlet A—for adulterer—pinned to her dress for the rest of her life. On the outskirts of Boston, she lives in exile. No one will socialize with her—not even those who have quietly committed similar sins, among them the father of her child, the saintly village preacher. The scarlet letter has “the effect of a spell, taking her out of the ordinary relations with humanity, and enclosing her in a sphere by herself.”

We read that story with a certain self-satisfaction: Such an old-fashioned tale! Even Hawthorne sneered at the Puritans, with their “sad-colored garments and grey steeple-crowned hats,” their strict conformism, their narrow minds and their hypocrisy. And today we are not just hip and modern; we live in a land governed by the rule of law; we have procedures designed to prevent the meting-out of unfair punishment. Scarlet letters are a thing of the past.

More here.

To be even remotely plausible, a computer model of the human mind must warp — and restrict — our commonsense definitions of intelligence, knowledge, understanding, and action. Larson discusses the renowned computer scientist Stuart Russell, who

To be even remotely plausible, a computer model of the human mind must warp — and restrict — our commonsense definitions of intelligence, knowledge, understanding, and action. Larson discusses the renowned computer scientist Stuart Russell, who  “We never said the welfare state is a substitute for socialism.” This staple of Harrington’s lecture tours had a flipside, his retort to old-school socialists: “Any idiot can nationalize a bank.” He said both things frequently after Mitterrand retreated. Harrington relied on his core message: bureaucratic collectivism is an unavoidable reality. The question is whether it can be wrested into a democratic and ethically decent form. Freedom will survive the ascendance of globalized markets and corporations only if it achieves economic democracy. Harrington had long argued that the market should operate within a plan, but in the mid-1980s his actual position shifted to the opposite. He conceived planning within a market framework on the model of Swedish and German social democracy—solidarity wages, full employment, co-determination, and collective worker funds. To many critics that smacked of selling out socialism. He replied: “To think that ‘socialization’ is a panacea is to ignore the socialist history of the twentieth century, including the experience of France under Mitterrand. I am for worker- and community-controlled ownership and for an immediate and practical program for full employment which approximates as much of that ideal as possible. No more. No less.”

“We never said the welfare state is a substitute for socialism.” This staple of Harrington’s lecture tours had a flipside, his retort to old-school socialists: “Any idiot can nationalize a bank.” He said both things frequently after Mitterrand retreated. Harrington relied on his core message: bureaucratic collectivism is an unavoidable reality. The question is whether it can be wrested into a democratic and ethically decent form. Freedom will survive the ascendance of globalized markets and corporations only if it achieves economic democracy. Harrington had long argued that the market should operate within a plan, but in the mid-1980s his actual position shifted to the opposite. He conceived planning within a market framework on the model of Swedish and German social democracy—solidarity wages, full employment, co-determination, and collective worker funds. To many critics that smacked of selling out socialism. He replied: “To think that ‘socialization’ is a panacea is to ignore the socialist history of the twentieth century, including the experience of France under Mitterrand. I am for worker- and community-controlled ownership and for an immediate and practical program for full employment which approximates as much of that ideal as possible. No more. No less.” In April, the New York Times

In April, the New York Times  Physics is extremely good at describing simple systems with relatively few moving parts. Sadly, the world is not like that; many phenomena of interest are complex, with multiple interacting parts and interesting things happening at multiple scales of length and time. One area where the techniques of physics overlap with the multi-scale property of complex systems is in the study of phase transitions, when a composite system transitions from one phase to another. Nigel Goldenfeld has made important contributions to the study of phase transitions in their own right (and mathematical techniques for dealing with them), and has also been successful at leveraging that understanding to study biological systems, from the genetic code to the tree of life.

Physics is extremely good at describing simple systems with relatively few moving parts. Sadly, the world is not like that; many phenomena of interest are complex, with multiple interacting parts and interesting things happening at multiple scales of length and time. One area where the techniques of physics overlap with the multi-scale property of complex systems is in the study of phase transitions, when a composite system transitions from one phase to another. Nigel Goldenfeld has made important contributions to the study of phase transitions in their own right (and mathematical techniques for dealing with them), and has also been successful at leveraging that understanding to study biological systems, from the genetic code to the tree of life. Salar Abdoh: I’ve read my share of books and articles over the years about Afghanistan and talked to people who spent stretches of time there, but it’s no exaggeration to say that I’ve never come across one person who has more in-the-field experience than you have about a land that few understand but many weigh in on, far too irresponsibly.

Salar Abdoh: I’ve read my share of books and articles over the years about Afghanistan and talked to people who spent stretches of time there, but it’s no exaggeration to say that I’ve never come across one person who has more in-the-field experience than you have about a land that few understand but many weigh in on, far too irresponsibly. JÓZEF CZAPSKI was a reserve officer in the Polish army when German and Soviet forces invaded his country in September 1939. His unit surrendered to the Soviets toward the end of that month. In “Memories of Starobielsk,” the 40-page essay that gives this collection, translated by Alissa Valles, its title, Czapski tells how he and his comrades were deceived by the promise that they would be sent through neutral territory to France, from where they could continue the fight against the Germans. Instead, they were marched eastward as prisoners of war, over the Soviet frontier:

JÓZEF CZAPSKI was a reserve officer in the Polish army when German and Soviet forces invaded his country in September 1939. His unit surrendered to the Soviets toward the end of that month. In “Memories of Starobielsk,” the 40-page essay that gives this collection, translated by Alissa Valles, its title, Czapski tells how he and his comrades were deceived by the promise that they would be sent through neutral territory to France, from where they could continue the fight against the Germans. Instead, they were marched eastward as prisoners of war, over the Soviet frontier: Simone de Beauvoir’s rucksack invariably contained a candle, an alarm clock, a copy of the local Guide Bleu, a Michelin map, and a felt-covered water bottle filled with red wine. She hadn’t always walked with a rucksack: when she arrived in Marseilles, age twenty-three, to take up her first teaching post, she’d walked with a basket. It was here, among the mountains, valleys, and cliffs of Provence, that a passion for solitary rambles and “communion with nature” first took hold of her. “I derived a satisfaction I had never known in all the rush and bustle of my Paris life,” she wrote in her memoir.

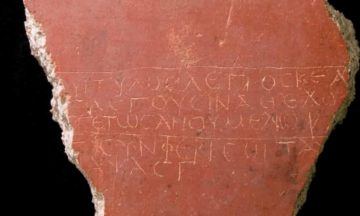

Simone de Beauvoir’s rucksack invariably contained a candle, an alarm clock, a copy of the local Guide Bleu, a Michelin map, and a felt-covered water bottle filled with red wine. She hadn’t always walked with a rucksack: when she arrived in Marseilles, age twenty-three, to take up her first teaching post, she’d walked with a basket. It was here, among the mountains, valleys, and cliffs of Provence, that a passion for solitary rambles and “communion with nature” first took hold of her. “I derived a satisfaction I had never known in all the rush and bustle of my Paris life,” she wrote in her memoir. For Taylor Swift, the “haters gonna hate”, but she’ll just “shake it off”. Now research by a Cambridge academic into a little-known ancient Greek text bearing much the same sentiment – “They say / What they like / Let them say it / I don’t care” – is set to cast a new light on the history of poetry and song.

For Taylor Swift, the “haters gonna hate”, but she’ll just “shake it off”. Now research by a Cambridge academic into a little-known ancient Greek text bearing much the same sentiment – “They say / What they like / Let them say it / I don’t care” – is set to cast a new light on the history of poetry and song. Twenty years ago, precisely on 9-11-2001, I was booked to fly out from NYC to Tehran. All flights were cancelled, so I witnessed the aftermath of the gruesome attack here in Manhattan. I wrote about what I saw and what I felt, drawing on what I then understood about the world. It was hardly a deep understanding especially about the Middle East, Iran, or Islamism, I admit. (That I was woefully unprepared to navigate the tumultuous waters of Middle Eastern geopolitics – which after 9-11 began churning with a new intensity – was something I would learn the hard way in the decade to come.) My essay “September 11: An Iranian In New York” was published in English in November after reaching Tehran. It was then published in Persian in one of Tehran’s main newspaper’s magazine edition. I have appended the Persian at the end this post.

Twenty years ago, precisely on 9-11-2001, I was booked to fly out from NYC to Tehran. All flights were cancelled, so I witnessed the aftermath of the gruesome attack here in Manhattan. I wrote about what I saw and what I felt, drawing on what I then understood about the world. It was hardly a deep understanding especially about the Middle East, Iran, or Islamism, I admit. (That I was woefully unprepared to navigate the tumultuous waters of Middle Eastern geopolitics – which after 9-11 began churning with a new intensity – was something I would learn the hard way in the decade to come.) My essay “September 11: An Iranian In New York” was published in English in November after reaching Tehran. It was then published in Persian in one of Tehran’s main newspaper’s magazine edition. I have appended the Persian at the end this post. The prose poem begins life as a paradox and a provocation. On Christmas Day 1861,

The prose poem begins life as a paradox and a provocation. On Christmas Day 1861,  Ideally there’d be a change in our norms of conversation. Relying on an anecdote, arguing ad hominem — these should be mortifying. Of course no one can engineer social norms explicitly. But we know that norms can change, and if there are seeds that try to encourage the process, then there is some chance that it could go viral. On the other hand, a conclusion that I came to in the book is that the most powerful means of getting people to be more rational is not to concentrate on the people. Because people are pretty rational when it comes to their own lives. They get the kids clothed and fed and off to school on time, and they keep their jobs and pay their bills. But people hold beliefs not because they are provably true or false but because they’re uplifting, they’re empowering, they’re good stories. The key, though, is what kind of species are we? How rational is Homo sapiens? The answer can’t be that we’re just irrational in our bones, otherwise we could never have established the benchmarks of rationality against which we could say some people some of the time are irrational.

Ideally there’d be a change in our norms of conversation. Relying on an anecdote, arguing ad hominem — these should be mortifying. Of course no one can engineer social norms explicitly. But we know that norms can change, and if there are seeds that try to encourage the process, then there is some chance that it could go viral. On the other hand, a conclusion that I came to in the book is that the most powerful means of getting people to be more rational is not to concentrate on the people. Because people are pretty rational when it comes to their own lives. They get the kids clothed and fed and off to school on time, and they keep their jobs and pay their bills. But people hold beliefs not because they are provably true or false but because they’re uplifting, they’re empowering, they’re good stories. The key, though, is what kind of species are we? How rational is Homo sapiens? The answer can’t be that we’re just irrational in our bones, otherwise we could never have established the benchmarks of rationality against which we could say some people some of the time are irrational. Although the aim of conflict is as it ever was—to destroy or degrade the enemy’s capacity and will to fight—at every level from the individual enemy soldier to the economic and political system behind them, war has changed in character. This evolution is prompting new and urgent ethical questions, particularly in relation to remote unmanned military machines. Surveillance and hunter-killer drones such as the Predator and the Reaper have become commonplace on the modern battlefield and their continued use suggests—perhaps indeed presages—a future of war in which the fighting is done by machines independent of direct human control. This scenario prompts great anxieties.

Although the aim of conflict is as it ever was—to destroy or degrade the enemy’s capacity and will to fight—at every level from the individual enemy soldier to the economic and political system behind them, war has changed in character. This evolution is prompting new and urgent ethical questions, particularly in relation to remote unmanned military machines. Surveillance and hunter-killer drones such as the Predator and the Reaper have become commonplace on the modern battlefield and their continued use suggests—perhaps indeed presages—a future of war in which the fighting is done by machines independent of direct human control. This scenario prompts great anxieties. America’s school board meetings are out of control.

America’s school board meetings are out of control.