Richard Hughes Gibson in The Hedgehog Review:

“Now he is scattered among a hundred cities,” W.H. Auden wrote in 1939, “And wholly given over to unfamiliar affections.” Auden was ruminating on the recent death of the Irish poet W.B. Yeats, but the words could serve as an epitaph for any great author. Poets like to imagine that their creations confer afterlives—for themselves and their subjects—impervious to the assaults of “wasteful war” and “sluttish time” so ruinous to monuments of marble or metal (see Horace’s Ode 3.30 and Shakespeare’s Sonnet 55). But as Auden recognized, the moment an author dies, his or her legacy is on the loose. Any chance those poems have of a future depends on what readers make of them: “The words of a dead man,” Auden continues, “Are modified in the guts of the living.”

“Now he is scattered among a hundred cities,” W.H. Auden wrote in 1939, “And wholly given over to unfamiliar affections.” Auden was ruminating on the recent death of the Irish poet W.B. Yeats, but the words could serve as an epitaph for any great author. Poets like to imagine that their creations confer afterlives—for themselves and their subjects—impervious to the assaults of “wasteful war” and “sluttish time” so ruinous to monuments of marble or metal (see Horace’s Ode 3.30 and Shakespeare’s Sonnet 55). But as Auden recognized, the moment an author dies, his or her legacy is on the loose. Any chance those poems have of a future depends on what readers make of them: “The words of a dead man,” Auden continues, “Are modified in the guts of the living.”

In Dante’s Divine Comedy: A Biography, Joseph Luzzi, literature professor at Bard College, offers a vivid account of this process of cultural digestion, and, at times, indigestion, from the Middle Ages to the present day. At first glance, such a slim book—little more than two hundred pages, including notes—would hardly seem adequate to the task, given the number, ardor, and productivity of Dante’s devotees over the centuries. Yet, as Luzzi argues in the introduction, those are exactly the reasons against attempting a truly comprehensive reception history of the Comedy (as Dante called it—Divine was added later by a Venetian printer). Such a study’s girth would be measured in hundreds of thousands of pages. No one would read it.

Instead, across ten chapters, Luzzi mixes passage analysis and brief case studies to illustrate the major trends in the Comedy’s reception.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Fourteen years ago, Noam Chomsky

Fourteen years ago, Noam Chomsky  Fragile quantum states might seem incompatible with the messy world of biology. But researchers have now coaxed cells to produce quantum sensors made of proteins. Quantum states are incredibly sensitive to changes in the environment. This is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they can

Fragile quantum states might seem incompatible with the messy world of biology. But researchers have now coaxed cells to produce quantum sensors made of proteins. Quantum states are incredibly sensitive to changes in the environment. This is a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they can  For women with breast cancer, stressors are associated with deleterious alterations to the systemic and tumor immune environment, according to a study

For women with breast cancer, stressors are associated with deleterious alterations to the systemic and tumor immune environment, according to a study  “Now he is scattered among a hundred cities,” W.H. Auden wrote in 1939, “And wholly given over to unfamiliar affections.” Auden was ruminating on the recent death of the Irish poet W.B. Yeats, but the words could serve as an epitaph for any great author. Poets like to imagine that their creations confer afterlives—for themselves and their subjects—impervious to the assaults of “wasteful war” and “sluttish time” so ruinous to monuments of marble or metal (see Horace’s Ode 3.30 and Shakespeare’s Sonnet 55). But as Auden recognized, the moment an author dies, his or her legacy is on the loose. Any chance those poems have of a future depends on what readers make of them: “The words of a dead man,” Auden continues, “Are modified in the guts of the living.”

“Now he is scattered among a hundred cities,” W.H. Auden wrote in 1939, “And wholly given over to unfamiliar affections.” Auden was ruminating on the recent death of the Irish poet W.B. Yeats, but the words could serve as an epitaph for any great author. Poets like to imagine that their creations confer afterlives—for themselves and their subjects—impervious to the assaults of “wasteful war” and “sluttish time” so ruinous to monuments of marble or metal (see Horace’s Ode 3.30 and Shakespeare’s Sonnet 55). But as Auden recognized, the moment an author dies, his or her legacy is on the loose. Any chance those poems have of a future depends on what readers make of them: “The words of a dead man,” Auden continues, “Are modified in the guts of the living.” The modern concept of GDP was developed in the 1930s and became firmly established during World War II, as it served a national purpose. While Germany was working on its own methods for gauging economic capacity, the United States and the United Kingdom gained a decisive strategic edge by being the first to define total output and compile reliable statistics. This enabled the Allies to maximize production and manage the sacrifices required of their citizens more effectively.

The modern concept of GDP was developed in the 1930s and became firmly established during World War II, as it served a national purpose. While Germany was working on its own methods for gauging economic capacity, the United States and the United Kingdom gained a decisive strategic edge by being the first to define total output and compile reliable statistics. This enabled the Allies to maximize production and manage the sacrifices required of their citizens more effectively. How will AI affect American workers? There are two major narratives floating around. The “

How will AI affect American workers? There are two major narratives floating around. The “ On Wednesday

On Wednesday The visible effects of ageing on our body are in part linked to invisible changes in gene activity. The epigenetic process of DNA methylation — the addition or removal of tags called methyl groups — becomes less precise as we age. The result is changes to gene expression that are linked to reduced organ function and increased susceptibility to disease as people age. Now, a meta-analysis of epigenetic changes in 17 types of human tissue throughout the entire adult lifespan provides the most comprehensive picture to date of how ageing modifies our genes.

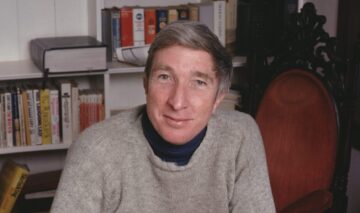

The visible effects of ageing on our body are in part linked to invisible changes in gene activity. The epigenetic process of DNA methylation — the addition or removal of tags called methyl groups — becomes less precise as we age. The result is changes to gene expression that are linked to reduced organ function and increased susceptibility to disease as people age. Now, a meta-analysis of epigenetic changes in 17 types of human tissue throughout the entire adult lifespan provides the most comprehensive picture to date of how ageing modifies our genes. Few American authors of the past century churned out as many words. Even peers who matched or exceeded Updike’s productivity when it came to novels, such as Philip Roth, could not keep pace when factoring in the numerous other modes in which he regularly put pen to paper: short stories, poems, book reviews, essays, a play, a memoir, and even five books for children. Multiple books appeared after his death, including a final volume of short stories, My Father’s Tears.

Few American authors of the past century churned out as many words. Even peers who matched or exceeded Updike’s productivity when it came to novels, such as Philip Roth, could not keep pace when factoring in the numerous other modes in which he regularly put pen to paper: short stories, poems, book reviews, essays, a play, a memoir, and even five books for children. Multiple books appeared after his death, including a final volume of short stories, My Father’s Tears. In 1974, five years before he wrote his Pulitzer Prize–winning book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid,

In 1974, five years before he wrote his Pulitzer Prize–winning book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid,  A postwar plan for Gaza circulating within the Trump administration, modeled on President Donald Trump’s vow to “take over” the enclave, would turn it into a trusteeship administered by the United States for at least 10 years while it is transformed into a gleaming tourism resort and high-tech manufacturing and technology hub.

A postwar plan for Gaza circulating within the Trump administration, modeled on President Donald Trump’s vow to “take over” the enclave, would turn it into a trusteeship administered by the United States for at least 10 years while it is transformed into a gleaming tourism resort and high-tech manufacturing and technology hub.