Brandon Kiem in Nautilus:

In the annals of transportation history persists a tale of how automobiles in the early 20th century helped cities conquer their waste problems. It’s a tidy story, so to speak, about dirty horses and clean cars and technological innovation. As typically told, it’s a lesson we can learn from today, now that cars are their own environmental disaster, and one that technology can no doubt solve. The story makes perfect sense to modern ears and noses: After all, Americans love their cars! And who’d want to walk through ankle-deep horse manure to buy a newspaper? There’s just one problem with the story. It’s wrong.

In the annals of transportation history persists a tale of how automobiles in the early 20th century helped cities conquer their waste problems. It’s a tidy story, so to speak, about dirty horses and clean cars and technological innovation. As typically told, it’s a lesson we can learn from today, now that cars are their own environmental disaster, and one that technology can no doubt solve. The story makes perfect sense to modern ears and noses: After all, Americans love their cars! And who’d want to walk through ankle-deep horse manure to buy a newspaper? There’s just one problem with the story. It’s wrong.

For a recent telling, you can turn to SuperFreakonomics, the best-selling 2009 book by economist Steven D. Levitt and journalist Stephen J. Dubner. The authors describe how, in the late 19th century, the streets of fast-industrializing cities were congested with horses, each pulling a cart or a coach, one after the other, in some places three abreast. There were something like 200,000 horses in New York City alone, depositing manure at a rate of roughly 35 pounds per day, per horse. It piled high in vacant lots and “lined city streets like banks of snow.” The elegant brownstone stoops so beloved of contemporary city-dwellers allowed homeowners to “rise above a sea of manure.” In Rochester, N. Y., health officials calculated that the city’s annual horse waste would, if collected on a single acre, make a 175-foot-tall tower.

“The world had seemingly reached the point where its largest cities could not survive without the horse but couldn’t survive with it, either,” write Levitt and Dubner. A main solution, as they portray it, came in the form of cars, which, compared to horses, were a godsend, their adoption inevitable. “The automobile, cheaper to own and operate than a horse-drawn vehicle was proclaimed an ‘environmental savior.’ Cities around the world were able to take a deep breath—without holding their noses at last—and resume their march of progress.” To Levitt and Dubner, this historical turnabout teaches that technological innovation solves problems, and if it creates new problems, innovation will solve those, too.

It’s far too simplistic an interpretation. Cars didn’t replace horses, at least not in the way we usually think, and it was social as much as technological progress that solved the era’s pollution problems. As we confront our current car troubles—particulate and greenhouse gas pollutions, accidents and deaths, wasteful swaths of the landscape dedicated to automobiles—these are lessons we’d do well to recall.

More here.

Gazing with recognition at this pig, Burhan also noticed the painted silhouettes of two human hands toward its rear. The over-all look of the art work suggested to Burhan that it was very old—but how old?

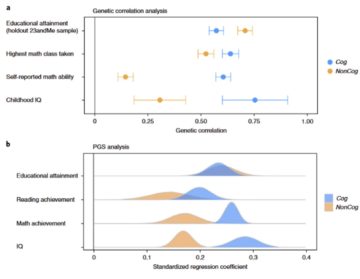

Gazing with recognition at this pig, Burhan also noticed the painted silhouettes of two human hands toward its rear. The over-all look of the art work suggested to Burhan that it was very old—but how old? Educational attainment is closely correlated with intelligence, but not perfectly correlated. How far you go in school depends not just on your IQ, but on other skills: how hard-working and motivated you are, how well you can cope with adversity – and arguably also less desirable qualities, like whether you so desperately seek societal approval that you’re willing to throw away your entire twenties on a PhD with no job prospects at the end of it. “Genes for educational attainment” will be a combination of genes for intelligence, and genes for this other stuff.

Educational attainment is closely correlated with intelligence, but not perfectly correlated. How far you go in school depends not just on your IQ, but on other skills: how hard-working and motivated you are, how well you can cope with adversity – and arguably also less desirable qualities, like whether you so desperately seek societal approval that you’re willing to throw away your entire twenties on a PhD with no job prospects at the end of it. “Genes for educational attainment” will be a combination of genes for intelligence, and genes for this other stuff. “Arabs” are not real people in these works of fiction. Arrakis in Dune are not Iraqis in their homeland. They are figurative, metaphoric and metonymic. They are a mere synecdoche for a literary historiography of American Orientalism. They are tropes – mockups that are there for the white narrator to tell his triumphant story.

“Arabs” are not real people in these works of fiction. Arrakis in Dune are not Iraqis in their homeland. They are figurative, metaphoric and metonymic. They are a mere synecdoche for a literary historiography of American Orientalism. They are tropes – mockups that are there for the white narrator to tell his triumphant story. H

H A friend of mine

A friend of mine Adam Shatz in the LRB’s blog:

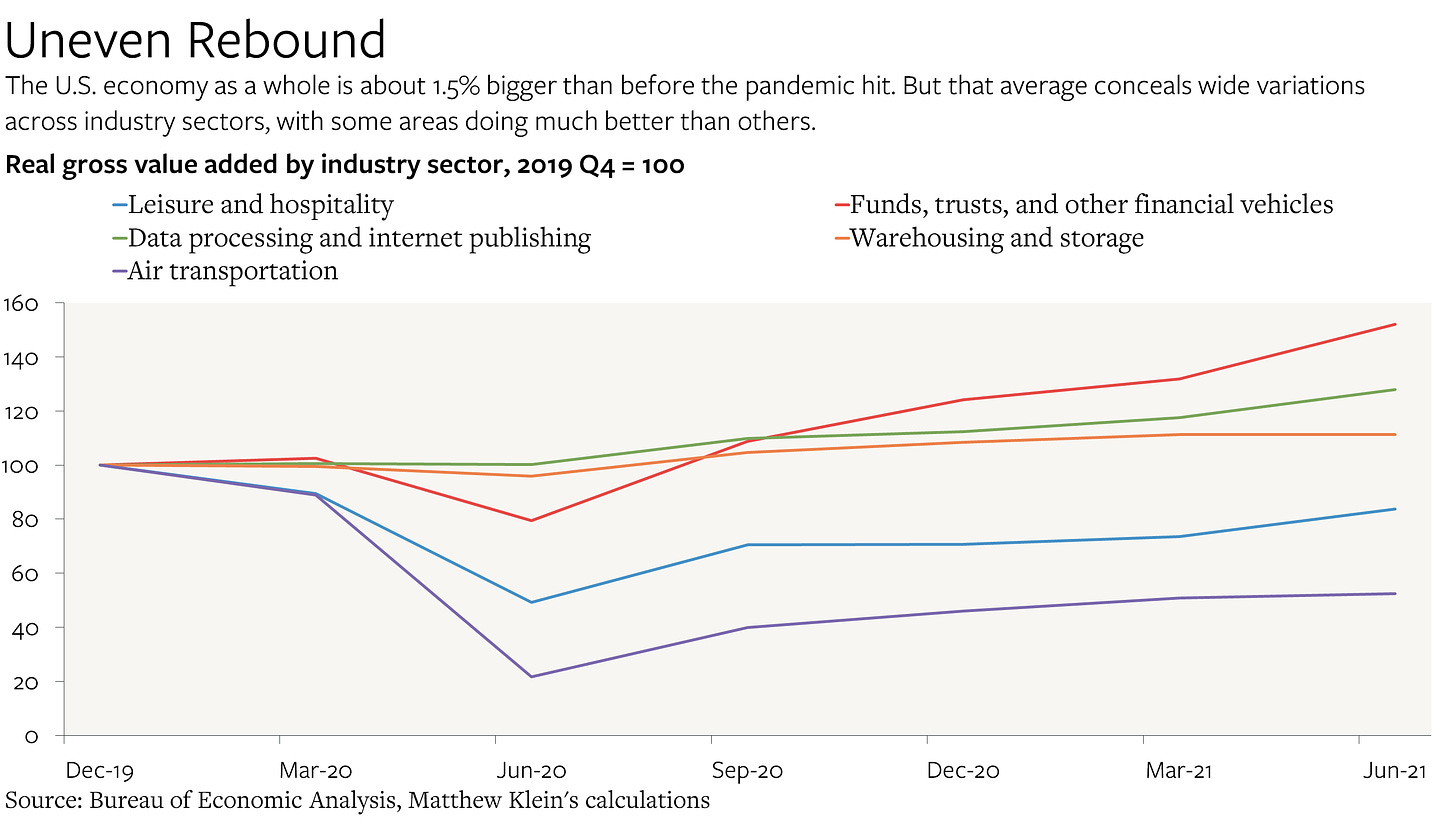

Adam Shatz in the LRB’s blog: Ho-fung Hung in Phenomenal World:

Ho-fung Hung in Phenomenal World:

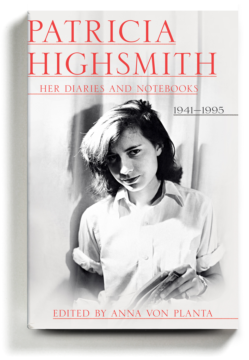

The future author of “Strangers on a Train,” the Ripley series and many other novels was learning to mediate between her intense appetite for work — few writers, these diaries make clear, had a stronger sense of vocation — and her need to lose herself in art, gin, music and warm bodies, most of them belonging to women.

The future author of “Strangers on a Train,” the Ripley series and many other novels was learning to mediate between her intense appetite for work — few writers, these diaries make clear, had a stronger sense of vocation — and her need to lose herself in art, gin, music and warm bodies, most of them belonging to women. I didn’t choose “Roadrunner” because its recording timeline and its image of a person literally circulating through the night allowed me to discuss these things. I chose it because it’s magic. I have felt its magic for a long time but never had a good story about it. And because I couldn’t figure out a path to a book about “Tell Me Something Good,” a song at least as magical. That book goes “Something something—wait! Did you know that Chaka Khan got the name ‘Chaka’ when she joined the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Chicago?” And I am not sure I know how to tell that story in a way that does justice to Chaka, and Rufus, and the BPPSD, and Chairman Fred. So there I was with “Roadrunner.” And once I set out along Route 128, there was no way for me not to situate it within what is for me the true metanarrative of the U.S. present: the catastrophic trajectory of capitalism.

I didn’t choose “Roadrunner” because its recording timeline and its image of a person literally circulating through the night allowed me to discuss these things. I chose it because it’s magic. I have felt its magic for a long time but never had a good story about it. And because I couldn’t figure out a path to a book about “Tell Me Something Good,” a song at least as magical. That book goes “Something something—wait! Did you know that Chaka Khan got the name ‘Chaka’ when she joined the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Chicago?” And I am not sure I know how to tell that story in a way that does justice to Chaka, and Rufus, and the BPPSD, and Chairman Fred. So there I was with “Roadrunner.” And once I set out along Route 128, there was no way for me not to situate it within what is for me the true metanarrative of the U.S. present: the catastrophic trajectory of capitalism. There’s an idea, particularly popular with some comedians, that the very point of comedy is to say the unsayable, to push boundaries and envelopes by articulating uncomfortable truths.

There’s an idea, particularly popular with some comedians, that the very point of comedy is to say the unsayable, to push boundaries and envelopes by articulating uncomfortable truths.  Imagine you are in a meadow picking flowers. You know that some flowers are safe, while others have a bee inside that will sting you. How would you react to this environment and, more importantly, how would your brain react? This is the scene in a virtual-reality environment used by researchers to understand the impact anxiety has on the brain and how brain regions interact with one another to shape behavior.

Imagine you are in a meadow picking flowers. You know that some flowers are safe, while others have a bee inside that will sting you. How would you react to this environment and, more importantly, how would your brain react? This is the scene in a virtual-reality environment used by researchers to understand the impact anxiety has on the brain and how brain regions interact with one another to shape behavior.