Slavoj Žižek in The Philosophical Salon:

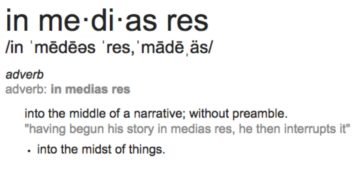

One of Mao Zedong’s best-known sayings is: “There is great disorder under heaven; the situation is excellent.” It is easy to understand what Mao meant here: when the existing social order is disintegrating, the ensuing chaos offers revolutionary forces a great chance to act decisively and assume political power. Today, there certainly is great disorder under heaven: the Covid-19 pandemic, global warming, signs of a new Cold War, and the eruption of popular protests and social antagonisms are just a few of the crises that beset us. But does this chaos still make the situation excellent, or is the danger of self-destruction too high? The difference between the situation that Mao had in mind and our own situation can be best rendered by a tiny terminological distinction. Mao speaks about disorder UNDER heaven, wherein “heaven,” or the big Other in whatever form—the inexorable logic of historical processes, the laws of social development—still exists and discreetly regulates social chaos. Today, we should talk about HEAVEN ITSELF as being in disorder. What do I mean by this?

One of Mao Zedong’s best-known sayings is: “There is great disorder under heaven; the situation is excellent.” It is easy to understand what Mao meant here: when the existing social order is disintegrating, the ensuing chaos offers revolutionary forces a great chance to act decisively and assume political power. Today, there certainly is great disorder under heaven: the Covid-19 pandemic, global warming, signs of a new Cold War, and the eruption of popular protests and social antagonisms are just a few of the crises that beset us. But does this chaos still make the situation excellent, or is the danger of self-destruction too high? The difference between the situation that Mao had in mind and our own situation can be best rendered by a tiny terminological distinction. Mao speaks about disorder UNDER heaven, wherein “heaven,” or the big Other in whatever form—the inexorable logic of historical processes, the laws of social development—still exists and discreetly regulates social chaos. Today, we should talk about HEAVEN ITSELF as being in disorder. What do I mean by this?

More here.

The term “gaslighting” has returned to the popular lexicon over the past decade, when as recently as the turn of the millennium it had fallen into near-complete disuse. It was then that I first heard the word myself, in the context of a Steely Dan song from 2000, “Gaslighting Abbie.” Not only did I have no idea what it meant, I had only the vaguest sense of who Steely Dan were. But I was, at least, in the right place: a university-district high-end stereo shop, the kind of audiophile’s sacred space that has provided countless “Danfans” their first proper experience of the band — that is, of the band’s records, played back on a sound system of high enough fidelity to do justice to the enormously costly, complex, and time-consuming labors of recording and production that went into them. “Gaslighting Abbie” alone required 26 straight eight-hour days in the studio to get right.

The term “gaslighting” has returned to the popular lexicon over the past decade, when as recently as the turn of the millennium it had fallen into near-complete disuse. It was then that I first heard the word myself, in the context of a Steely Dan song from 2000, “Gaslighting Abbie.” Not only did I have no idea what it meant, I had only the vaguest sense of who Steely Dan were. But I was, at least, in the right place: a university-district high-end stereo shop, the kind of audiophile’s sacred space that has provided countless “Danfans” their first proper experience of the band — that is, of the band’s records, played back on a sound system of high enough fidelity to do justice to the enormously costly, complex, and time-consuming labors of recording and production that went into them. “Gaslighting Abbie” alone required 26 straight eight-hour days in the studio to get right. In his essay Sexual Objectification, Timo Jütten explains how sexual objectification teaches men and women to assume roles as superiors and subordinates, roles that disadvantage women and leave them vulnerable to gender-specific harms, such as sexual assault and rape. While I knew this already, it is a small relief to read it in print. Most women instinctively know that their bodies are a hair’s breadth away from violence. The artist Marina Abramović demonstrated this by laying seventy-two objects on a table—a tube of lipstick, a feather, a knife, and a gun—and invited gallery viewers to do whatever they wanted to her for six hours. At first the people were shy, presenting her with the flower, kissing her, draping her in cloth; then as the hours ticked off, one man snipped off her clothes with the scissors so that she was bare, and another sliced her with the knife. Someone else picked up the gun from the table, wrapped her hand around it, and pointed it at her neck. At the end she stood up to leave, bare, and bleeding, and the audience fled.

In his essay Sexual Objectification, Timo Jütten explains how sexual objectification teaches men and women to assume roles as superiors and subordinates, roles that disadvantage women and leave them vulnerable to gender-specific harms, such as sexual assault and rape. While I knew this already, it is a small relief to read it in print. Most women instinctively know that their bodies are a hair’s breadth away from violence. The artist Marina Abramović demonstrated this by laying seventy-two objects on a table—a tube of lipstick, a feather, a knife, and a gun—and invited gallery viewers to do whatever they wanted to her for six hours. At first the people were shy, presenting her with the flower, kissing her, draping her in cloth; then as the hours ticked off, one man snipped off her clothes with the scissors so that she was bare, and another sliced her with the knife. Someone else picked up the gun from the table, wrapped her hand around it, and pointed it at her neck. At the end she stood up to leave, bare, and bleeding, and the audience fled. Readers of Edgar Allan Poe’s most famous prose and poetry might be unaware of how often he wrote about science. As John Tresch explains in “The Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science,” in the late 1840s, near the end of his life, Poe had established for himself “a unique position as fiction writer, poet, critic, and expert on scientific matters – crossing paths with and learning from those who were producing the ‘apparent miracles’ of modern science.”

Readers of Edgar Allan Poe’s most famous prose and poetry might be unaware of how often he wrote about science. As John Tresch explains in “The Reason for the Darkness of the Night: Edgar Allan Poe and the Forging of American Science,” in the late 1840s, near the end of his life, Poe had established for himself “a unique position as fiction writer, poet, critic, and expert on scientific matters – crossing paths with and learning from those who were producing the ‘apparent miracles’ of modern science.” Daniela Gabor in Phenomenal World:

Daniela Gabor in Phenomenal World: Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar:

Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar: Adam Tooze over at site Chartbook:

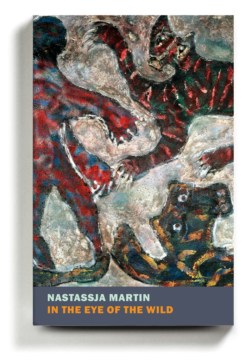

Adam Tooze over at site Chartbook: “Attack” didn’t seem like the right word, and neither did “mauling.” In Nastassja Martin’s new book, “In the Eye of the Wild,” she calls it “combat” before eventually settling on “the encounter between the bear and me.” She suggests that what happened on Aug. 25, 2015, in the mountains of Kamchatka, in eastern Siberia, wasn’t simply a matter of a fierce animal overpowering a terrified human — though Martin almost died before she pulled out the ice ax she was carrying and drove it into the bear’s leg. Waiting for help, she saw that everything was red: her face, her hands, the ground.

“Attack” didn’t seem like the right word, and neither did “mauling.” In Nastassja Martin’s new book, “In the Eye of the Wild,” she calls it “combat” before eventually settling on “the encounter between the bear and me.” She suggests that what happened on Aug. 25, 2015, in the mountains of Kamchatka, in eastern Siberia, wasn’t simply a matter of a fierce animal overpowering a terrified human — though Martin almost died before she pulled out the ice ax she was carrying and drove it into the bear’s leg. Waiting for help, she saw that everything was red: her face, her hands, the ground. W

W Stephen Sondheim, one of Broadway history’s songwriting titans, whose music and lyrics raised and reset the artistic standard for the American stage musical, died early Friday at his home in Roxbury, Conn. He was 91. His lawyer and friend, F. Richard Pappas, announced the death. He said he did not know the cause but added that Mr. Sondheim had not been known to be ill and that the death was sudden. The day before, Mr. Sondheim had celebrated Thanksgiving with a dinner with friends in Roxbury, Mr. Pappas said.

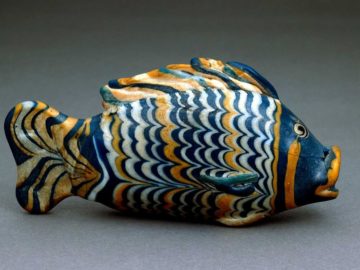

Stephen Sondheim, one of Broadway history’s songwriting titans, whose music and lyrics raised and reset the artistic standard for the American stage musical, died early Friday at his home in Roxbury, Conn. He was 91. His lawyer and friend, F. Richard Pappas, announced the death. He said he did not know the cause but added that Mr. Sondheim had not been known to be ill and that the death was sudden. The day before, Mr. Sondheim had celebrated Thanksgiving with a dinner with friends in Roxbury, Mr. Pappas said. Today, glass is ordinary, on-the-kitchen-shelf stuff. But early in its history, glass was bling for kings. Thousands of years ago, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt surrounded themselves with the stuff, even in death, leaving stunning specimens for archaeologists to uncover. King Tutankhamen’s tomb housed a

Today, glass is ordinary, on-the-kitchen-shelf stuff. But early in its history, glass was bling for kings. Thousands of years ago, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt surrounded themselves with the stuff, even in death, leaving stunning specimens for archaeologists to uncover. King Tutankhamen’s tomb housed a

Fraud in biomedical research, though relatively uncommon, damages the scientific community by diminishing the integrity of the ecosystem and sending other scientists down fruitless paths. When exposed and publicized, fraud also reduces public respect for the research enterprise, which is required for its success. Although the human frailties that contribute to fraud are as old as our species, the response of the research community to allegations of fraud has dramatically changed. This is well illustrated by three prominent cases known to the author over 40 years. In the first, I participated as auditor in an ad hoc process that, lacking institutional definition and oversight, was open to abuse, though it eventually produced an appropriate result. In the second, I was a faculty colleague of a key participant whose case helped shape guidelines for management of future cases. The third transpired during my time overseeing the well-developed if sometimes overly bureaucratized investigatory process for research misconduct at Harvard Medical School, designed in accordance with prevailing regulations. These cases illustrate many of the factors contributing to fraudulent biomedical research in the modern era and the changing institutional responses to it, which should further evolve to be more efficient and transparent.

Fraud in biomedical research, though relatively uncommon, damages the scientific community by diminishing the integrity of the ecosystem and sending other scientists down fruitless paths. When exposed and publicized, fraud also reduces public respect for the research enterprise, which is required for its success. Although the human frailties that contribute to fraud are as old as our species, the response of the research community to allegations of fraud has dramatically changed. This is well illustrated by three prominent cases known to the author over 40 years. In the first, I participated as auditor in an ad hoc process that, lacking institutional definition and oversight, was open to abuse, though it eventually produced an appropriate result. In the second, I was a faculty colleague of a key participant whose case helped shape guidelines for management of future cases. The third transpired during my time overseeing the well-developed if sometimes overly bureaucratized investigatory process for research misconduct at Harvard Medical School, designed in accordance with prevailing regulations. These cases illustrate many of the factors contributing to fraudulent biomedical research in the modern era and the changing institutional responses to it, which should further evolve to be more efficient and transparent.