Emily Tamkin in New Statesman:

WASHINGTON, DC – Donald Trump lost the 2020 presidential election.

Donald Trump, however, will not say this. He has spent the year since he lost insisting that he won. His supporters believe the same. According to an NBC News poll from November, 38 per cent of respondents did not believe that President Joe Biden was legitimately elected, and half of Republicans did not believe their ballots would be counted accurately the next time they went to vote. “There are always some sour grapes from the losing party after the election,” said Barry Burden, a political science professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “But this has gone to a new level of disbelief.” Just as troubling are the other steps that Trump and his supporters have taken in the past year to undermine American democracy, both for his own benefit and that of the Republicans aligned to him. They are not only refusing to accept reality but are trying to change the reality of how people vote in the future. “There really has not been anything like this in modern American history,” Burden said.

Donald Trump, however, will not say this. He has spent the year since he lost insisting that he won. His supporters believe the same. According to an NBC News poll from November, 38 per cent of respondents did not believe that President Joe Biden was legitimately elected, and half of Republicans did not believe their ballots would be counted accurately the next time they went to vote. “There are always some sour grapes from the losing party after the election,” said Barry Burden, a political science professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “But this has gone to a new level of disbelief.” Just as troubling are the other steps that Trump and his supporters have taken in the past year to undermine American democracy, both for his own benefit and that of the Republicans aligned to him. They are not only refusing to accept reality but are trying to change the reality of how people vote in the future. “There really has not been anything like this in modern American history,” Burden said.

Official intimidation

Over the past year, election officials in various places across the country have been threatened. A study conducted by Benenson Strategy Group found that a third of election officials expressed concern about facing harassment in the course of doing their job, and 17 per cent had already been threatened. The For the People Act, a voting rights bill passed by the House of Representatives, does contain some protections for election officials – but the bill is stalled in the Senate. Unless moderate Democrats Kyrsten Sinema and Joe Manchin agree to abolish the filibuster, it will not pass, since Republicans will not support it.

More here.

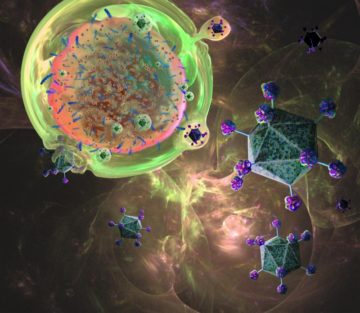

It seemed like a very promising cancer immunotherapy lead. CHO Pharma, in Taiwan, had discovered that it was possible to target solid tumours with an antibody against a cell-surface glycolipid called SSEA-4.

It seemed like a very promising cancer immunotherapy lead. CHO Pharma, in Taiwan, had discovered that it was possible to target solid tumours with an antibody against a cell-surface glycolipid called SSEA-4.

The detonation of the

The detonation of the  Jean Luc remembers how, when he was very young, his parents would leave their house in Kimihurura, a neighborhood of Kigali, once a month in a good mood. He didn’t know what they were smiling about.

Jean Luc remembers how, when he was very young, his parents would leave their house in Kimihurura, a neighborhood of Kigali, once a month in a good mood. He didn’t know what they were smiling about. Purgatory seems to be on people’s minds this year – we have several new translations of Dante’s canticle to consider in time for Christmas. Fortunately, we have Dantista

Purgatory seems to be on people’s minds this year – we have several new translations of Dante’s canticle to consider in time for Christmas. Fortunately, we have Dantista  Today in 1982, Gabriel García Márquez

Today in 1982, Gabriel García Márquez  “An argument without end” is how Joseph J. Ellis characterizes history in “The Cause: The American Revolution and Its Discontents, 1773-1783,” one of several notable fall releases on America’s Revolutionary War era. Like “The Cause,” new works by historians H.W. Brands and Woody Holton and novelist Matthew Pearl, making his nonfiction debut, are evidence that when it comes to the story of America’s origins, the argument continues to evolve. These books look beyond the Founding Fathers to consider early American history from a fascinating range of perspectives.

“An argument without end” is how Joseph J. Ellis characterizes history in “The Cause: The American Revolution and Its Discontents, 1773-1783,” one of several notable fall releases on America’s Revolutionary War era. Like “The Cause,” new works by historians H.W. Brands and Woody Holton and novelist Matthew Pearl, making his nonfiction debut, are evidence that when it comes to the story of America’s origins, the argument continues to evolve. These books look beyond the Founding Fathers to consider early American history from a fascinating range of perspectives. What do economics, biological evolution, and democracy have in common? They are all complex adaptive systems. This realization reflects one of the core strengths of a diverse intellectual background – there are meaningful commonalities underlying different systems and areas of knowledge. In fact, science and academia themselves are complex adaptive systems that benefit from diversity of knowledge and perspective. All such systems benefit from diversity, and suffer when that diversity is narrowed, possibly even fatally.

What do economics, biological evolution, and democracy have in common? They are all complex adaptive systems. This realization reflects one of the core strengths of a diverse intellectual background – there are meaningful commonalities underlying different systems and areas of knowledge. In fact, science and academia themselves are complex adaptive systems that benefit from diversity of knowledge and perspective. All such systems benefit from diversity, and suffer when that diversity is narrowed, possibly even fatally. For Ghosh, our insistence on carrying on as normal in the face of the unthinkable is the enabling madness at the centre of modernity’s addiction to extraction and consumption. At a time in which ‘the wild has become the norm,’ and ‘freak’ events such as tornadoes are becoming more common, he wrote, we are suffering in the ‘West’ from a ‘crisis of imagination’.

For Ghosh, our insistence on carrying on as normal in the face of the unthinkable is the enabling madness at the centre of modernity’s addiction to extraction and consumption. At a time in which ‘the wild has become the norm,’ and ‘freak’ events such as tornadoes are becoming more common, he wrote, we are suffering in the ‘West’ from a ‘crisis of imagination’. The bicycle, as we know it today, was not invented until the late 1800s. Yet it was a simple mechanical invention. It would seem to require no brilliant inventive insight, and certainly no scientific background.

The bicycle, as we know it today, was not invented until the late 1800s. Yet it was a simple mechanical invention. It would seem to require no brilliant inventive insight, and certainly no scientific background. My paternal grandfather Anis was born an Ottoman subject in 1885 but died an Arab citizen. He passed away in 1977 at the age of 92, two years into Lebanon’s civil war. Raised in Tripoli when all the Arab East lay under Ottoman sovereignty, and educated in American mission schools that dotted the Empire in its last century, Anis Khoury Makdisi became a distinguished professor of Arabic at the American University of Beirut. Best known for his works on Arabic literature, he was known as ‘Ustadh Anis’ – a teacher of generations of students of Arabic in the Middle East’s most renowned modern university. He was also a proud member of the Arabic language academies of Cairo and of Damascus, institutions that embodied a modern age of coexistence that shaped the Arab Muslims, Christians and Jews of my grandfather’s generation.

My paternal grandfather Anis was born an Ottoman subject in 1885 but died an Arab citizen. He passed away in 1977 at the age of 92, two years into Lebanon’s civil war. Raised in Tripoli when all the Arab East lay under Ottoman sovereignty, and educated in American mission schools that dotted the Empire in its last century, Anis Khoury Makdisi became a distinguished professor of Arabic at the American University of Beirut. Best known for his works on Arabic literature, he was known as ‘Ustadh Anis’ – a teacher of generations of students of Arabic in the Middle East’s most renowned modern university. He was also a proud member of the Arabic language academies of Cairo and of Damascus, institutions that embodied a modern age of coexistence that shaped the Arab Muslims, Christians and Jews of my grandfather’s generation. This story begins about two billion years ago, when the world, if not young, exactly, was a lot more impressionable. The planet spun faster, so the sun rose every twenty-one hours. The earliest continents were forming—Arctica, for instance, which persists as bits and pieces of Siberia. Most of the globe was given over to oceans, and the oceans teemed with microbes.

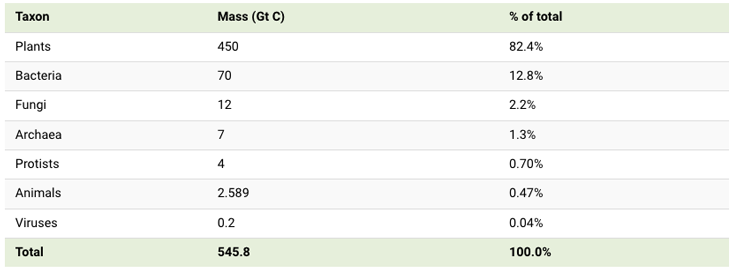

This story begins about two billion years ago, when the world, if not young, exactly, was a lot more impressionable. The planet spun faster, so the sun rose every twenty-one hours. The earliest continents were forming—Arctica, for instance, which persists as bits and pieces of Siberia. Most of the globe was given over to oceans, and the oceans teemed with microbes. Our planet supports approximately

Our planet supports approximately

Robert Lowell is, for me, the inescapable elder poet, and Day by Day is the inescapable book. It is where you go if you want to see where American poetry last set into major balance an art fully aware of its traditions and an experimental openness to unliterary raw material. Leaving behind the ruck and rubble of Notebook and History, it steps beyond the Cyclopean masonry blocks of the unrhymed sonnets of The Dolphin and ventures into irregular but adamantine shapes of feeling and thought. The smashed sonnets may suggest the smashed life or lives the book loosely recounts: aging friends, dead friends, dead parents, are summoned; a marriage is chronicled in its dilapidations; mental breakdown sends the suffering speaker once again to a hospital. From these wreckages and from the wreck of stricter verse form, Lowell has saved the aphoristic essentials, and broken through to poetic renewal in the very recognition of failure. Sacrifice, truly executed, earns recompense, and these poems do.

Robert Lowell is, for me, the inescapable elder poet, and Day by Day is the inescapable book. It is where you go if you want to see where American poetry last set into major balance an art fully aware of its traditions and an experimental openness to unliterary raw material. Leaving behind the ruck and rubble of Notebook and History, it steps beyond the Cyclopean masonry blocks of the unrhymed sonnets of The Dolphin and ventures into irregular but adamantine shapes of feeling and thought. The smashed sonnets may suggest the smashed life or lives the book loosely recounts: aging friends, dead friends, dead parents, are summoned; a marriage is chronicled in its dilapidations; mental breakdown sends the suffering speaker once again to a hospital. From these wreckages and from the wreck of stricter verse form, Lowell has saved the aphoristic essentials, and broken through to poetic renewal in the very recognition of failure. Sacrifice, truly executed, earns recompense, and these poems do. A

A