Alexandra Jacobs at the New York Times:

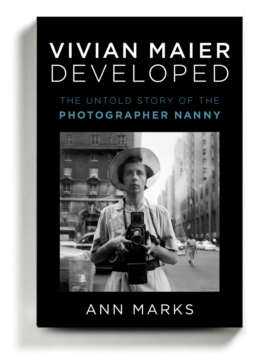

If a picture were still worth a thousand words, we’d know more than enough by now about Vivian Maier, the so-called photographer nanny whose vast trove of images was discovered piecemeal and not fully processed, in all senses of the word, after her death at 83 in 2009, just as the iPhone was going wide.

If a picture were still worth a thousand words, we’d know more than enough by now about Vivian Maier, the so-called photographer nanny whose vast trove of images was discovered piecemeal and not fully processed, in all senses of the word, after her death at 83 in 2009, just as the iPhone was going wide.

Long before we were all carrying around those little wafers of pleasure and misery, Maier made constant companions of her Brownies, Leicas and Rolleiflexes. The ensuing record of her movement throughout the world — at least 140,000 negatives of landscapes, common folk, celebrities, children, animals and garbage — has more range and rigor than any influencer’s. Despite recurring selfies, some in noirish shadow, Maier was in fact the anti-influencer: Her startling compositions were not only largely unshared and unsponsored during her lifetime — she made abortive attempts to start a postcard business — but almost entirely unseen.

more here.

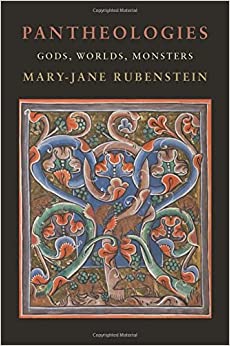

In this book, she explores the history of intellectual discussions of pantheism, and raises questions about why so many Western philosophers and theologians have resisted this concept. Pantheism is combined of two Greek words, pan—which means ‘all’—and theism, which consists of belief in God. Here All is God, or God is All. In most of Western thought, pantheism functions as a limit concept. That is, if we want to think about or have faith in a divinity, it needs to be related to the world, the all or everything, but pantheism names the collapse of this God into everything else to the extent that there is nothing that is not God.

In this book, she explores the history of intellectual discussions of pantheism, and raises questions about why so many Western philosophers and theologians have resisted this concept. Pantheism is combined of two Greek words, pan—which means ‘all’—and theism, which consists of belief in God. Here All is God, or God is All. In most of Western thought, pantheism functions as a limit concept. That is, if we want to think about or have faith in a divinity, it needs to be related to the world, the all or everything, but pantheism names the collapse of this God into everything else to the extent that there is nothing that is not God.

If you’re wondering whether we’ll do anything about global warming before it destroys civilization, think about this ominous fact: It occupies barely any space in popular culture.

If you’re wondering whether we’ll do anything about global warming before it destroys civilization, think about this ominous fact: It occupies barely any space in popular culture. Researchers with the

Researchers with the  “P

“P The

The

Don Quixote is the Saturday Night Live of the Spanish Inquisition. Cervantes roasts everybody, including the Catholic Church and even the reader. This magnum opus—called by many the first Western novel—is really a book about reading: Carlos Fuentes famously said of Quixote: “Su lectura es su locura.” [“His reading is his madness.”] Quixote reads too much (if that’s possible) and wants to become the literary heroes of his books. But just who are those heroes?

Don Quixote is the Saturday Night Live of the Spanish Inquisition. Cervantes roasts everybody, including the Catholic Church and even the reader. This magnum opus—called by many the first Western novel—is really a book about reading: Carlos Fuentes famously said of Quixote: “Su lectura es su locura.” [“His reading is his madness.”] Quixote reads too much (if that’s possible) and wants to become the literary heroes of his books. But just who are those heroes? IN OSAKA, JAPAN,

IN OSAKA, JAPAN, In advanced economies, earnings for those with less education often stagnated despite gains in overall labor productivity. Since 1979, for example, US production workers’ compensation has risen by

In advanced economies, earnings for those with less education often stagnated despite gains in overall labor productivity. Since 1979, for example, US production workers’ compensation has risen by  There have been many English Baudelaires through the 150 years since his death, two dozen reasonably ample selected poems, and a dozen or so Les Fleurs du mal (a new one arrives next month, translated by

There have been many English Baudelaires through the 150 years since his death, two dozen reasonably ample selected poems, and a dozen or so Les Fleurs du mal (a new one arrives next month, translated by  Religion and sincerity go hand in hand, and neither one is particularly associated with Andy Warhol, whose name is synonymous with ironic, detached irreverence. But you don’t have to dig very deep in Warhol’s biography or catalog to find plenty of both. Warhol was Byzantine Catholic, a denomination combining aspects of both Western and Eastern rites. He went to church with his mother almost every Sunday until her death in 1974 and attended regularly in the years after. One of his last diary entries, two months before his death, records that he “went to the Church of Heavenly Rest to pass out Interviews and feed the poor.” It’s impossible to know for sure where the limit of irony lies with an artist like Warhol; maybe he went to Church as a bit. But his deep superstitions and his fear of dying, at least, seem to have been very real, even before he was nearly assassinated.

Religion and sincerity go hand in hand, and neither one is particularly associated with Andy Warhol, whose name is synonymous with ironic, detached irreverence. But you don’t have to dig very deep in Warhol’s biography or catalog to find plenty of both. Warhol was Byzantine Catholic, a denomination combining aspects of both Western and Eastern rites. He went to church with his mother almost every Sunday until her death in 1974 and attended regularly in the years after. One of his last diary entries, two months before his death, records that he “went to the Church of Heavenly Rest to pass out Interviews and feed the poor.” It’s impossible to know for sure where the limit of irony lies with an artist like Warhol; maybe he went to Church as a bit. But his deep superstitions and his fear of dying, at least, seem to have been very real, even before he was nearly assassinated.