Vladimir Nabokov in the New York Review of Books:

Silence fell. Pitilessly illuminated by the lamplight, young and plump-faced, wearing a side-buttoned Russian blouse under his black jacket, his eyes tensely downcast, Anton Golïy began gathering the manuscript pages that he had discarded helter-skelter during his reading. His mentor, the critic from Red Reality, stared at the floor as he patted his pockets in search of some matches. The writer Novodvortsev was silent too, but his was a different, venerable, silence. Wearing a substantial pince-nez, exceptionally large of forehead, two strands of his sparse dark hair pulled across his bald pate, gray streaks on his close-cropped temples, he sat with closed eyes as if he were still listening, his heavy legs crossed and one hand compressed between a kneecap and a hamstring. This was not the first time he had been subjected to such glum, earnest rustic fictionists. And not the first time he had detected, in their immature narratives, echoes—not yet noted by the critics—of his own twenty-five years of writing; for Golïy’s story was a clumsy rehash of one of his subjects, that of The Verge, a novella he had excitedly and hopefully composed, whose publication the previous year had done nothing to enhance his secure but pallid reputation.

Silence fell. Pitilessly illuminated by the lamplight, young and plump-faced, wearing a side-buttoned Russian blouse under his black jacket, his eyes tensely downcast, Anton Golïy began gathering the manuscript pages that he had discarded helter-skelter during his reading. His mentor, the critic from Red Reality, stared at the floor as he patted his pockets in search of some matches. The writer Novodvortsev was silent too, but his was a different, venerable, silence. Wearing a substantial pince-nez, exceptionally large of forehead, two strands of his sparse dark hair pulled across his bald pate, gray streaks on his close-cropped temples, he sat with closed eyes as if he were still listening, his heavy legs crossed and one hand compressed between a kneecap and a hamstring. This was not the first time he had been subjected to such glum, earnest rustic fictionists. And not the first time he had detected, in their immature narratives, echoes—not yet noted by the critics—of his own twenty-five years of writing; for Golïy’s story was a clumsy rehash of one of his subjects, that of The Verge, a novella he had excitedly and hopefully composed, whose publication the previous year had done nothing to enhance his secure but pallid reputation.

More here.

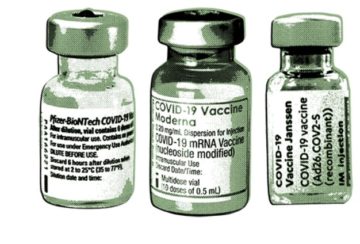

Imagine being in a pandemic, isolated and inert. Your life feels out of control, and you are stressed, not sleeping well. Then a raft of bewildering new symptoms arrive – perhaps your heart races unexpectedly, or you feel lightheaded. Maybe your stomach churns and parts of your body seem to have an alarming life of their own, all insisting something is badly wrong. You are less afraid of the pandemic than of the person you have now become.

Imagine being in a pandemic, isolated and inert. Your life feels out of control, and you are stressed, not sleeping well. Then a raft of bewildering new symptoms arrive – perhaps your heart races unexpectedly, or you feel lightheaded. Maybe your stomach churns and parts of your body seem to have an alarming life of their own, all insisting something is badly wrong. You are less afraid of the pandemic than of the person you have now become. Want a good, solid, rollicking laugh? Contemplate the end of the world—the whole existential shebang: the annihilation of civilization, the extinction of all species, the death of the entire Earthly biomass. Funny, right? Actually, yes—and arch and ironic and dark and smart, at least in the hands of

Want a good, solid, rollicking laugh? Contemplate the end of the world—the whole existential shebang: the annihilation of civilization, the extinction of all species, the death of the entire Earthly biomass. Funny, right? Actually, yes—and arch and ironic and dark and smart, at least in the hands of  When Dr. Wilson began his career in evolutionary biology in the 1950s, the study of animals and plants seemed to many scientists like a quaint, obsolete hobby. Molecular biologists were getting their first glimpses of DNA, proteins and other invisible foundations of life. Dr. Wilson made it his life’s work to put evolution on an equal footing. “How could our seemingly old-fashioned subjects achieve new intellectual rigor and originality compared to molecular biology?” he recalled in 2009. He answered his own question by pioneering new fields of research. As an expert on insects, Dr. Wilson studied the evolution of behavior, exploring how natural selection and other forces could produce something as extraordinarily complex as an ant colony. He then championed this kind of research as a way of making sense of all behavior — including our own. As part of his campaign, Dr. Wilson wrote a string of books that influenced his fellow scientists while also gaining a broad public audience. “On Human Nature” won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction in 1979; “The Ants,” which Dr. Wilson wrote with his longtime colleague Bert Hölldobler, won him his second Pulitzer, in 1991.

When Dr. Wilson began his career in evolutionary biology in the 1950s, the study of animals and plants seemed to many scientists like a quaint, obsolete hobby. Molecular biologists were getting their first glimpses of DNA, proteins and other invisible foundations of life. Dr. Wilson made it his life’s work to put evolution on an equal footing. “How could our seemingly old-fashioned subjects achieve new intellectual rigor and originality compared to molecular biology?” he recalled in 2009. He answered his own question by pioneering new fields of research. As an expert on insects, Dr. Wilson studied the evolution of behavior, exploring how natural selection and other forces could produce something as extraordinarily complex as an ant colony. He then championed this kind of research as a way of making sense of all behavior — including our own. As part of his campaign, Dr. Wilson wrote a string of books that influenced his fellow scientists while also gaining a broad public audience. “On Human Nature” won the Pulitzer Prize for general nonfiction in 1979; “The Ants,” which Dr. Wilson wrote with his longtime colleague Bert Hölldobler, won him his second Pulitzer, in 1991. On the afternoon of Christmas Day 1956, in a snow-covered field on the outskirts of the small Swiss town of Herisau, some children and their dog discovered the body of a dead man, hand clutched tight to his stilled heart. It was the writer Robert Walser, who had died that day, aged seventy-eight, while out walking far from the mental institution where he had dwelled for the previous two decades. A photograph taken by the local medical examiner Kurt Giezendanner shows the body at rest, left arm thrown out as in the style of a sleeper midway through a restless night, while two shadowy figures at the margins look on. The sorrow of the scene is rather gently assuaged by the odd fact that Walser’s hat, perhaps moved by a breeze, lies at a modest distance from his body, as if it has leapt off his head to cartoonishly express surprise at its owner’s death. A few distant trees squeeze into the top of the frame like awkward mourners paying their respects. The snow, even on the ground but for a few shaggy lumps close to his boots, appears at first to be nothing more than a dazzling absence, as if the dead Walser were floating on a white winter sky.

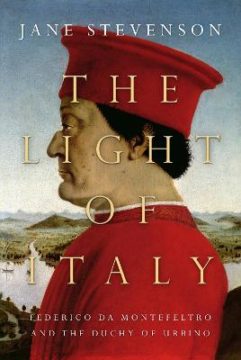

On the afternoon of Christmas Day 1956, in a snow-covered field on the outskirts of the small Swiss town of Herisau, some children and their dog discovered the body of a dead man, hand clutched tight to his stilled heart. It was the writer Robert Walser, who had died that day, aged seventy-eight, while out walking far from the mental institution where he had dwelled for the previous two decades. A photograph taken by the local medical examiner Kurt Giezendanner shows the body at rest, left arm thrown out as in the style of a sleeper midway through a restless night, while two shadowy figures at the margins look on. The sorrow of the scene is rather gently assuaged by the odd fact that Walser’s hat, perhaps moved by a breeze, lies at a modest distance from his body, as if it has leapt off his head to cartoonishly express surprise at its owner’s death. A few distant trees squeeze into the top of the frame like awkward mourners paying their respects. The snow, even on the ground but for a few shaggy lumps close to his boots, appears at first to be nothing more than a dazzling absence, as if the dead Walser were floating on a white winter sky. Federico is a figure well worthy of attention. Born on the wrongish side of the blanket in 1420s (it was a crowded part of the bed at that time in Italy), he became ruler of Urbino in his early twenties after the assassination of his unpopular half-brother. While there is no evidence that he was involved in the plot, he was hovering conveniently nearby when it happened. The citizens who approached him to take over presented him with a list of unnegotiable demands, the most stringent of which was to abolish a set of recently introduced taxes and promise not to impose new ones. In itself, this was an impressive demand in a country filled with minor despots. Even more impressively, Federico kept his word.

Federico is a figure well worthy of attention. Born on the wrongish side of the blanket in 1420s (it was a crowded part of the bed at that time in Italy), he became ruler of Urbino in his early twenties after the assassination of his unpopular half-brother. While there is no evidence that he was involved in the plot, he was hovering conveniently nearby when it happened. The citizens who approached him to take over presented him with a list of unnegotiable demands, the most stringent of which was to abolish a set of recently introduced taxes and promise not to impose new ones. In itself, this was an impressive demand in a country filled with minor despots. Even more impressively, Federico kept his word. This year, mercifully, saw quite a few notable improvements

This year, mercifully, saw quite a few notable improvements  Matthew Mehan

Matthew Mehan Cities are bastions of opportunity. They are filled with vast numbers of people meeting friends and family, visiting restaurants, museums, concert halls and sporting events, and travelling to and from jobs. Yet many of us who live in cities have occasionally been overwhelmed by the activity. At other times, we might feel ‘alone in the crowd’. For decades, the conflicting experiences of city living have led urbanites and scholars to ask: are cities bad for mental health?

Cities are bastions of opportunity. They are filled with vast numbers of people meeting friends and family, visiting restaurants, museums, concert halls and sporting events, and travelling to and from jobs. Yet many of us who live in cities have occasionally been overwhelmed by the activity. At other times, we might feel ‘alone in the crowd’. For decades, the conflicting experiences of city living have led urbanites and scholars to ask: are cities bad for mental health? NASA just got a $10 billion space telescope for Christmas.

NASA just got a $10 billion space telescope for Christmas.

If there’s one thing we’ve learned

If there’s one thing we’ve learned  Joe Bucciero in The Nation:

Joe Bucciero in The Nation: Lisa Herzog in The Raven:

Lisa Herzog in The Raven: Massimo Pigliucci in Aeon:

Massimo Pigliucci in Aeon: