Akhil Sharma in The New Yorker:

Not long after we began dating, my now wife, Christine, and I started making up stories about the child we might have.

Not long after we began dating, my now wife, Christine, and I started making up stories about the child we might have.

We named the child—or, in the stories we told about him, he named himself—Suzuki Noguchi. Among the things we liked about him was that he was cheerfully indifferent to us. He did not wish to be either Irish (like Christine) or Indian (like me). Suzuki was eight, and he chose this name because he was into Japanese high fashion. When we told him that he couldn’t just go around claiming to be Japanese, Suzuki said that he was a child of God and who were we to say that God was not Japanese. In addition to being a dandy, Suzuki was a criminal. He dealt in yellowcake uranium and trafficked in endangered animals. Sometimes we asked him how his day at school had gone and he would warn, “Do you really want to be an accessory after the fact?” We imagined him banging on our bedroom door when we were having sex and shouting, “Stop! You can’t get any child better than me.”

My wife was forty-eight and I was forty-seven, and we started inventing these stories as a form of play. It also soothed some hurt part of us.

More here.

Smashing the patriarchy in the human world has been easier said than done. But last year, a 9-year-old female Japanese macaque in a reserve in southern Japan showed humans how it’s done by violently overthrowing the alpha male of her troop to become its first female leader in the reserve’s 70-year history. The macaque, named Yakei, presides over a troop of 677 monkeys in Takasakiyama Natural Zoological Garden, which was established as a reserve for monkeys in 1952. There are two troops on the island reserve, and they spend most of their time roaming the forested mountain at its center. They also make daily visits to a park at the base of the mountain, where the staff provides food. Since the reserve opened, its staff has kept tabs on the romantic and political struggles of its simian residents.

Smashing the patriarchy in the human world has been easier said than done. But last year, a 9-year-old female Japanese macaque in a reserve in southern Japan showed humans how it’s done by violently overthrowing the alpha male of her troop to become its first female leader in the reserve’s 70-year history. The macaque, named Yakei, presides over a troop of 677 monkeys in Takasakiyama Natural Zoological Garden, which was established as a reserve for monkeys in 1952. There are two troops on the island reserve, and they spend most of their time roaming the forested mountain at its center. They also make daily visits to a park at the base of the mountain, where the staff provides food. Since the reserve opened, its staff has kept tabs on the romantic and political struggles of its simian residents. One of the primary sticking points that prevents me from being a Marxist, even as I think Marxist analysis is the most illuminating framework we have for making sense of history and economics, is that I could never abide the idea of false consciousness. Another way of putting this is that Marxism is pretty adequate for the study of history and economics, utterly inadequate for anthropology, which I tend to care about most of all, and for which I think an anarchist lens is most revealing. Do you really want to tell a Nuer herdsman that the cattle-centric cosmology he uses to understand his place in the world is just an artefact of ideology, flowing from the relations of labor that prevail in his society and of which he remains ignorant? Wouldn’t it perhaps be more interesting to see what happens when you take his word for it, about what a cow is, for example, and how cows relate to human beings? And if you are willing to approach a Nuer herdsman in this way, why not also a concitoyen of yours who thinks Nascar is the ultimate thrill, or a lower-bourgeois French person who thinks no holiday meal is complete without pigs’ feet in aspic and who simply adores Johann Strauss’s “Blue Danube”?

One of the primary sticking points that prevents me from being a Marxist, even as I think Marxist analysis is the most illuminating framework we have for making sense of history and economics, is that I could never abide the idea of false consciousness. Another way of putting this is that Marxism is pretty adequate for the study of history and economics, utterly inadequate for anthropology, which I tend to care about most of all, and for which I think an anarchist lens is most revealing. Do you really want to tell a Nuer herdsman that the cattle-centric cosmology he uses to understand his place in the world is just an artefact of ideology, flowing from the relations of labor that prevail in his society and of which he remains ignorant? Wouldn’t it perhaps be more interesting to see what happens when you take his word for it, about what a cow is, for example, and how cows relate to human beings? And if you are willing to approach a Nuer herdsman in this way, why not also a concitoyen of yours who thinks Nascar is the ultimate thrill, or a lower-bourgeois French person who thinks no holiday meal is complete without pigs’ feet in aspic and who simply adores Johann Strauss’s “Blue Danube”? Hailed as the

Hailed as the  Last spring, prominent Big Tech critic Lina Khan became the new chair of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)—an appointment widely seen as a coup for progressive reform. In her confirmation hearing, she characterized the agency’s overarching goal in terms of “fair competition.” This choice of emphasis is significant for understanding the antitrust reform project of which Khan is a leader. At its core, the project is a policy paradigm aimed at creating fair markets—markets characterized by socially beneficial competition, fair prices, and decent wages.

Last spring, prominent Big Tech critic Lina Khan became the new chair of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)—an appointment widely seen as a coup for progressive reform. In her confirmation hearing, she characterized the agency’s overarching goal in terms of “fair competition.” This choice of emphasis is significant for understanding the antitrust reform project of which Khan is a leader. At its core, the project is a policy paradigm aimed at creating fair markets—markets characterized by socially beneficial competition, fair prices, and decent wages. Previously, researchers focused on

Previously, researchers focused on  Forster began writing Maurice in 1913, when the British Empire governed nearly a quarter of the earth’s population and the question of nostalgia was beside the point. Forster was thirty-four, eighteen years had passed since

Forster began writing Maurice in 1913, when the British Empire governed nearly a quarter of the earth’s population and the question of nostalgia was beside the point. Forster was thirty-four, eighteen years had passed since  Arriving at the chess board is like entering an eagerly anticipated party. All my old friends are there: the royal couple, their associates, the reassuringly straight lines of noble infantry. I adjust them, ensuring that they are optimally located in the centre of their starting squares, an anxious fidgeting and tactile caress. I know these pieces, and care about them. They are my responsibility. And I’m grateful to my opponent for obliging me to treat them well on pain of death.

Arriving at the chess board is like entering an eagerly anticipated party. All my old friends are there: the royal couple, their associates, the reassuringly straight lines of noble infantry. I adjust them, ensuring that they are optimally located in the centre of their starting squares, an anxious fidgeting and tactile caress. I know these pieces, and care about them. They are my responsibility. And I’m grateful to my opponent for obliging me to treat them well on pain of death. Andrew Yamakawa Elrod in Phenomenal World (image: Reprint from the September 1966 issue of AFL-CIO American Federationist, Box 38, Folder 4, William Page Keeton Papers, Special Collections, Tarlton Law Library, The University of Texas at Austin):

Andrew Yamakawa Elrod in Phenomenal World (image: Reprint from the September 1966 issue of AFL-CIO American Federationist, Box 38, Folder 4, William Page Keeton Papers, Special Collections, Tarlton Law Library, The University of Texas at Austin): Katie J. M. Baker in Lux:

Katie J. M. Baker in Lux: Roosevelt Montás over at Aeon:

Roosevelt Montás over at Aeon:

I

I The literary scholar Christopher Ricks made a distinction between being “unenchanted” and “disenchanted.” The latter category implies that you have been let down in your hopes and dreams; the former that you never had any to begin with. Didion, of course, belongs to the first breed. Nothing ever seemed to excite her or faze her or disappoint her, largely because she set her sights so low to begin with. She cannot be disabused. Spotting Jim Morrison on a spring evening in 1968 recording a rhythm track leads her to comment on his outfit — “black vinyl pants and no underwear” — and the gnomic remark (one of her specialties) that his whole gestalt suggested “some range of the possible just beyond a suicide pact.” Didion was the archpriestess of cool — possessed of a corrosive sense of irony and an overriding habit of condescension — in a period of greater naïveté and belief than we live in now.

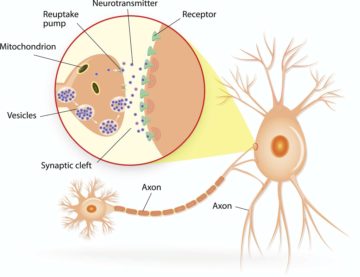

The literary scholar Christopher Ricks made a distinction between being “unenchanted” and “disenchanted.” The latter category implies that you have been let down in your hopes and dreams; the former that you never had any to begin with. Didion, of course, belongs to the first breed. Nothing ever seemed to excite her or faze her or disappoint her, largely because she set her sights so low to begin with. She cannot be disabused. Spotting Jim Morrison on a spring evening in 1968 recording a rhythm track leads her to comment on his outfit — “black vinyl pants and no underwear” — and the gnomic remark (one of her specialties) that his whole gestalt suggested “some range of the possible just beyond a suicide pact.” Didion was the archpriestess of cool — possessed of a corrosive sense of irony and an overriding habit of condescension — in a period of greater naïveté and belief than we live in now. Just after graduating from medical school, Carl Erik Fisher was on top of the world. He was winning awards and working day and night. But a lot of that frantic activity was really covering up his problems with addiction. Fisher – who says he comes from a family with a history of addiction – descended into an alcohol and Adderall binge during residency. A manic episode led to his admission to the Bellevue Hospital Psychiatry ward in New York, where just years ago, he’d interviewed for residency. “Because I was a doctor, because I’m white, because when the NYPD came to get me out of my apartment I was living in an upscale neighborhood —I got a lot of treatment and I got a lot of compassion,” he says. “Sadly, many people with addiction can’t even access services, let alone the kind of quality of services I was able to get.”

Just after graduating from medical school, Carl Erik Fisher was on top of the world. He was winning awards and working day and night. But a lot of that frantic activity was really covering up his problems with addiction. Fisher – who says he comes from a family with a history of addiction – descended into an alcohol and Adderall binge during residency. A manic episode led to his admission to the Bellevue Hospital Psychiatry ward in New York, where just years ago, he’d interviewed for residency. “Because I was a doctor, because I’m white, because when the NYPD came to get me out of my apartment I was living in an upscale neighborhood —I got a lot of treatment and I got a lot of compassion,” he says. “Sadly, many people with addiction can’t even access services, let alone the kind of quality of services I was able to get.”