Rachel Cooke at The Guardian:

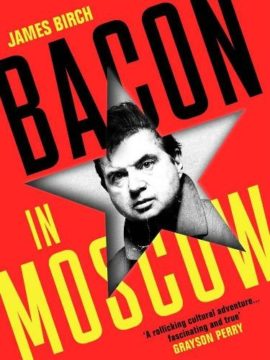

In July 1986, James Birch, a young London gallerist with vague designs on global domination, set off for the Soviet Union. It was his first visit and he had no idea what to expect. Mikhail Gorbachev had then been general secretary of the Communist party for one year: perestroika and glasnost were in the air (or, at any rate, in the British newspapers). But still, Moscow was a world apart. On the advice of his travelling companion, a “cultural entrepreneur” whose carpet business often took him to the USSR, Birch carried among his luggage a packet of chocolate digestives, just in case he found himself short of food, and cartons of Camel cigarettes, to be used as payment to all the drivers he would have to flag for a lift, there being virtually no taxis in the city.

In July 1986, James Birch, a young London gallerist with vague designs on global domination, set off for the Soviet Union. It was his first visit and he had no idea what to expect. Mikhail Gorbachev had then been general secretary of the Communist party for one year: perestroika and glasnost were in the air (or, at any rate, in the British newspapers). But still, Moscow was a world apart. On the advice of his travelling companion, a “cultural entrepreneur” whose carpet business often took him to the USSR, Birch carried among his luggage a packet of chocolate digestives, just in case he found himself short of food, and cartons of Camel cigarettes, to be used as payment to all the drivers he would have to flag for a lift, there being virtually no taxis in the city.

more here.

We’re in a room on the ground floor of a hotel, the bed facing a wall of curtained windows that in turn faces the street. It is nighttime. Rain is coming down, steadily, reflectively, a stream of passersby visible through the curtains, which are sheer. Everyone is moving in the same direction, bent slightly forward and holding an umbrella, from left to right, the good direction, from past to future, the opposite of where Death leads the knight and the squire and the monk and the smith and the mute in their final dance against the backdrop of time in Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. The umbrella is the canopy of the heavens; the rain is never going to let up. We can see the passersby but they can’t see us, though Eric has turned a light on above his side of the bed.

We’re in a room on the ground floor of a hotel, the bed facing a wall of curtained windows that in turn faces the street. It is nighttime. Rain is coming down, steadily, reflectively, a stream of passersby visible through the curtains, which are sheer. Everyone is moving in the same direction, bent slightly forward and holding an umbrella, from left to right, the good direction, from past to future, the opposite of where Death leads the knight and the squire and the monk and the smith and the mute in their final dance against the backdrop of time in Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. The umbrella is the canopy of the heavens; the rain is never going to let up. We can see the passersby but they can’t see us, though Eric has turned a light on above his side of the bed. Here is a test. Scott, Shackleton, Mawson, Amundsen — who comes next? As surely as “10” follows the pattern 2, 4, 6, 8, by almost any measure “Fiennes” is the name that should come after the other four synonymous with Antarctic exploration. To give him his full moniker, Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes has probably man-hauled sledges farther, endured more blizzards and lost more fingertips to frostbite than the rest of them put together.

Here is a test. Scott, Shackleton, Mawson, Amundsen — who comes next? As surely as “10” follows the pattern 2, 4, 6, 8, by almost any measure “Fiennes” is the name that should come after the other four synonymous with Antarctic exploration. To give him his full moniker, Sir Ranulph Twisleton-Wykeham-Fiennes has probably man-hauled sledges farther, endured more blizzards and lost more fingertips to frostbite than the rest of them put together. The creature appears to be, at first glance, a parrot, with bright feathers in yellow, red, green, and blue. But another look, and one sees that it’s shaped more like a duck, or perhaps two ducks melded into one. What looks like an eye might really be the wing of a butterfly. The more closely one looks at the image, the more the creature is unrecognizable; it dissolves into a strange jumble of component parts, which seem to add up to nothing, and then cohere once again into something both familiar and unknown.

The creature appears to be, at first glance, a parrot, with bright feathers in yellow, red, green, and blue. But another look, and one sees that it’s shaped more like a duck, or perhaps two ducks melded into one. What looks like an eye might really be the wing of a butterfly. The more closely one looks at the image, the more the creature is unrecognizable; it dissolves into a strange jumble of component parts, which seem to add up to nothing, and then cohere once again into something both familiar and unknown. SHE CALLED HERSELF a minor writer. “I’m no Tolstoy,” said this woman whose parents named her after a character from War and Peace. One wishes Natalia Ginzburg hadn’t apologized for her gifts. Wishes that she had luxuriated in her standing as one of Italy’s finest postwar writers. The fact that her various novels, novellas, and essays are flying back into print—some freshly translated—thirty years after her passing is not unrelated to the extravagant success of the other Italian, the one whose books have become the stuff of prestige television. Ginzburg, alas, has no HBO series attached to her name, but surely her estate profits from the fumes of Ferrante fever. As publishers scramble to chart distinguished genealogies of Italian women writers, we are invited to “discover” Ginzburg’s work in essays like this one. As though it had not been hiding in plain sight for decades.

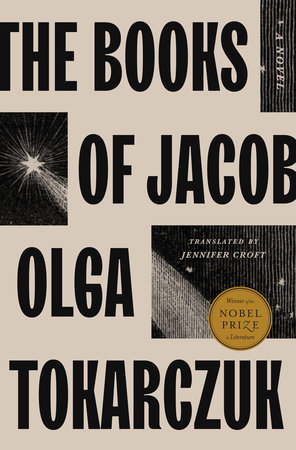

SHE CALLED HERSELF a minor writer. “I’m no Tolstoy,” said this woman whose parents named her after a character from War and Peace. One wishes Natalia Ginzburg hadn’t apologized for her gifts. Wishes that she had luxuriated in her standing as one of Italy’s finest postwar writers. The fact that her various novels, novellas, and essays are flying back into print—some freshly translated—thirty years after her passing is not unrelated to the extravagant success of the other Italian, the one whose books have become the stuff of prestige television. Ginzburg, alas, has no HBO series attached to her name, but surely her estate profits from the fumes of Ferrante fever. As publishers scramble to chart distinguished genealogies of Italian women writers, we are invited to “discover” Ginzburg’s work in essays like this one. As though it had not been hiding in plain sight for decades. The Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk was, in 2019, a youthful

The Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk was, in 2019, a youthful  Being a human is tricky. There are any number of unwritten rules and social cues that we have to learn as we go, but that we ultimately learn to take for granted. Camilla Pang, who was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at age eight, had a harder time than most, as she didn’t easily perceive the rules of etiquette and relationships that we need to deal with each other. But she ultimately figured them out, with the help of analogies and examples from different fields of science. We talk about these rules, and how science can help us think about them.

Being a human is tricky. There are any number of unwritten rules and social cues that we have to learn as we go, but that we ultimately learn to take for granted. Camilla Pang, who was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder at age eight, had a harder time than most, as she didn’t easily perceive the rules of etiquette and relationships that we need to deal with each other. But she ultimately figured them out, with the help of analogies and examples from different fields of science. We talk about these rules, and how science can help us think about them. According to a number of

According to a number of  David Byrne is all about connectedness these days. “Everybody’s

David Byrne is all about connectedness these days. “Everybody’s Researchers have explored the cellular changes that occur in human mammary tissue in lactating and non-lactating women, offering insight into the relationship between pregnancy, lactation, and breast cancer. The study was led by researchers from the Wellcome-MRC Cambridge Stem Cell Institute (CSCI) and the Department of Pharmacology at the University of Cambridge. Breast tissue is dynamic, changing over time during puberty, pregnancy, breastfeeding, and aging. The paper, published today in the journal Nature Communications, focuses on the changes that take place during lactation by investigating

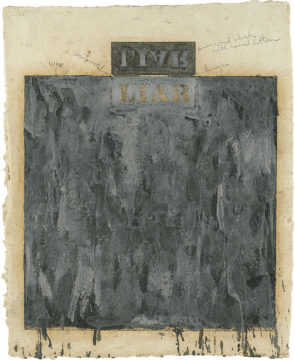

Researchers have explored the cellular changes that occur in human mammary tissue in lactating and non-lactating women, offering insight into the relationship between pregnancy, lactation, and breast cancer. The study was led by researchers from the Wellcome-MRC Cambridge Stem Cell Institute (CSCI) and the Department of Pharmacology at the University of Cambridge. Breast tissue is dynamic, changing over time during puberty, pregnancy, breastfeeding, and aging. The paper, published today in the journal Nature Communications, focuses on the changes that take place during lactation by investigating  In contrast with this array of translucence, viscosity, gleam, Johns exploits the matte, the opaque, the alkaline. His wax encaustic, charcoal, grease, paint stick all militate—it would seem—against sheen.

In contrast with this array of translucence, viscosity, gleam, Johns exploits the matte, the opaque, the alkaline. His wax encaustic, charcoal, grease, paint stick all militate—it would seem—against sheen. McLuhan’s impact on journalism was significant. His message was that all the techniques and values of Victorian liberal journalism should be discarded. The old-fashioned search for truth, using the tools of balance, objectivity, and impartiality, no longer applied. Although greeted with indifference or derision by older journalists, McLuhan’s insight was a Damascene moment for many young writers. As one underground journalist explained in 1966:

McLuhan’s impact on journalism was significant. His message was that all the techniques and values of Victorian liberal journalism should be discarded. The old-fashioned search for truth, using the tools of balance, objectivity, and impartiality, no longer applied. Although greeted with indifference or derision by older journalists, McLuhan’s insight was a Damascene moment for many young writers. As one underground journalist explained in 1966: In the fall

In the fall Mis- and disinformation, partisanship and polarization, crisis points and public trust—the big problems of 2022 were tackled by Walter Lippmann in his book

Mis- and disinformation, partisanship and polarization, crisis points and public trust—the big problems of 2022 were tackled by Walter Lippmann in his book