Oliver Milman in WIRED:

WHAT, THOUGH, IF we don’t act quickly enough? If the fall of insects’ tiny empires causes whole ecosystems to unravel, toppling previously solid certainties about the way our world functions, what then? It’s easy to foresee how diminishing supplies of certain foods and crashing wildlife populations will heap cascading suffering on the poor and vulnerable, given the lopsided nature of societies, and perhaps even stoke embers of resentment and nationalism as foundational resources become scarcer. It’s also reasonable to anticipate that we will reflexively grasp for a technological fix to the mess we’ve created.

WHAT, THOUGH, IF we don’t act quickly enough? If the fall of insects’ tiny empires causes whole ecosystems to unravel, toppling previously solid certainties about the way our world functions, what then? It’s easy to foresee how diminishing supplies of certain foods and crashing wildlife populations will heap cascading suffering on the poor and vulnerable, given the lopsided nature of societies, and perhaps even stoke embers of resentment and nationalism as foundational resources become scarcer. It’s also reasonable to anticipate that we will reflexively grasp for a technological fix to the mess we’ve created.

Expectation is already being ladled upon projects, still in their infancy, to create genetically modified pollinators resistant to disease and chemicals or to fashion machines topped with tiny cannons that fire pollen at plants and therefore address some of the causes of the climate collapse. Other scientists have turned their ingenuity to replicating the form and function of winged insects—researchers at Harvard University have devised diminutive robots that can swim before exploding out of the water into flight,

More here.

THERE IS AN ALMOST CHARMING

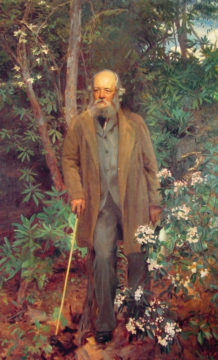

THERE IS AN ALMOST CHARMING What would Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903) make of his works today, in the bicentennial year of his birth? No doubt he would be delighted by the survival and continued popularity of so many of his big-city parks, particularly Central Park and Prospect Park, but also parks in Boston, Chicago, and Montreal, as well as Buffalo, Detroit, Rochester, and Louisville. He might be surprised by the bewildering range of activities these parks now accommodate—not only boating and ice-skating, as in his day, but exercising, jogging, picnicking, and games, as well as popular theatrical and musical events. I don’t think this variety would displease him. After all, it was he who introduced free band concerts in Central Park, over the objections of many of his strait-laced colleagues. He would be pleased by the banning of automobiles; his winding carriage drives were never intended for fast—and noisy—traffic.

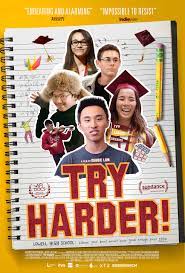

What would Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903) make of his works today, in the bicentennial year of his birth? No doubt he would be delighted by the survival and continued popularity of so many of his big-city parks, particularly Central Park and Prospect Park, but also parks in Boston, Chicago, and Montreal, as well as Buffalo, Detroit, Rochester, and Louisville. He might be surprised by the bewildering range of activities these parks now accommodate—not only boating and ice-skating, as in his day, but exercising, jogging, picnicking, and games, as well as popular theatrical and musical events. I don’t think this variety would displease him. After all, it was he who introduced free band concerts in Central Park, over the objections of many of his strait-laced colleagues. He would be pleased by the banning of automobiles; his winding carriage drives were never intended for fast—and noisy—traffic. These anxieties about status are acutely felt among a cohort for whom going to college can seem a foregone conclusion. Asian Americans are often held up as a “model minority,” a group whose presence on campuses like Harvard or M.I.T., where forty per cent of incoming first-years self-identify as Asian American, far outpaces their percentage of the U.S. population. The figure of the model minority emerged in the fifties, a reflection of Cold War-era policies that were designed to attract highly educated immigrants from Asia. Over time, this stereotype ossified. American meritocracy held up the immigrant as proof that its rules were fair, and many high achievers were flattered to play along. Even though many of the gains for Asian Americans could be explained through policy—and even as studies showed how entire swaths of the community were left behind in poverty—the experience of being Asian in America has been rigidly defined by a framework of success and failure. As the scholar erin Khuê Ninh argues in “

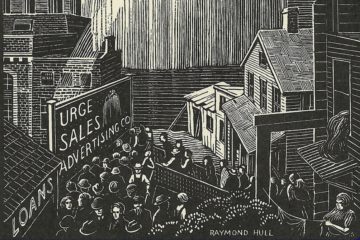

These anxieties about status are acutely felt among a cohort for whom going to college can seem a foregone conclusion. Asian Americans are often held up as a “model minority,” a group whose presence on campuses like Harvard or M.I.T., where forty per cent of incoming first-years self-identify as Asian American, far outpaces their percentage of the U.S. population. The figure of the model minority emerged in the fifties, a reflection of Cold War-era policies that were designed to attract highly educated immigrants from Asia. Over time, this stereotype ossified. American meritocracy held up the immigrant as proof that its rules were fair, and many high achievers were flattered to play along. Even though many of the gains for Asian Americans could be explained through policy—and even as studies showed how entire swaths of the community were left behind in poverty—the experience of being Asian in America has been rigidly defined by a framework of success and failure. As the scholar erin Khuê Ninh argues in “ “Those who can, do science,” the economist Paul Samuelson once remarked. “Those who can’t, prattle on about methodology.” Until fairly recently this seemed to be the dominant attitude among mainstream economists, but a sea change came when the global financial system began to unravel in 2007. In the decade and a half since—painful years of sluggish recovery, stagnating real wages, yawning inequality, and populist upheaval—reflexive talk has exploded. Why was the crash not widely predicted? Was the “efficient market hypothesis” to blame? Have lessons from the Great Depression been forgotten? And why are core questions about finance, power, inequality, and capitalism still largely missing from Economics 101?

“Those who can, do science,” the economist Paul Samuelson once remarked. “Those who can’t, prattle on about methodology.” Until fairly recently this seemed to be the dominant attitude among mainstream economists, but a sea change came when the global financial system began to unravel in 2007. In the decade and a half since—painful years of sluggish recovery, stagnating real wages, yawning inequality, and populist upheaval—reflexive talk has exploded. Why was the crash not widely predicted? Was the “efficient market hypothesis” to blame? Have lessons from the Great Depression been forgotten? And why are core questions about finance, power, inequality, and capitalism still largely missing from Economics 101? The united states

The united states “Why is Ukraine the West’s fault?” This is the provocative title of a talk by Professor John Mearsheimer – a famous exponent of international relations (IR) realism – given at an alumni gathering of the University of Chicago in 2015. Since it was first posted on

“Why is Ukraine the West’s fault?” This is the provocative title of a talk by Professor John Mearsheimer – a famous exponent of international relations (IR) realism – given at an alumni gathering of the University of Chicago in 2015. Since it was first posted on  “Does Anyone Have the Right to Sex?” was a shrewd yet compassionate essay, marked by rigorous thinking as well as the hope that we might make room for desires that don’t follow patriarchy’s scripts, without blaming people for desiring what they’ve been told to want. Srinivasan gestured in the essay toward a new feminist perspective, one that would draw on the work of the second-wave feminists of the 1960s and ’70s, who took questions of sexual desire seriously, without replicating some of their blind spots concerning race and class. Such a perspective would also preserve aspects of more recent feminist thinking—an emphasis on individual freedom, an awareness of the ways different forms of oppression intersect—without suggesting that desire is inherently good or just. Her aim was not to legislate anyone’s desires—that would be authoritarian—but rather to encourage readers to question their sexual preferences, to see their own desires as a starting point for inquiry rather than its end. There is no right to sex, she wrote, but there may be “a duty to transfigure, as best we can, our desires” so that they better align with our political goals

“Does Anyone Have the Right to Sex?” was a shrewd yet compassionate essay, marked by rigorous thinking as well as the hope that we might make room for desires that don’t follow patriarchy’s scripts, without blaming people for desiring what they’ve been told to want. Srinivasan gestured in the essay toward a new feminist perspective, one that would draw on the work of the second-wave feminists of the 1960s and ’70s, who took questions of sexual desire seriously, without replicating some of their blind spots concerning race and class. Such a perspective would also preserve aspects of more recent feminist thinking—an emphasis on individual freedom, an awareness of the ways different forms of oppression intersect—without suggesting that desire is inherently good or just. Her aim was not to legislate anyone’s desires—that would be authoritarian—but rather to encourage readers to question their sexual preferences, to see their own desires as a starting point for inquiry rather than its end. There is no right to sex, she wrote, but there may be “a duty to transfigure, as best we can, our desires” so that they better align with our political goals Understanding this complex tangle of overlapping titles and jurisdictions is here essential. For although Maria Theresa was sovereign in her own right of the archduchy of Austria and queen of Hungary, in legal theory she ranked lower than her husband, the newly elected emperor. Yet having regained her realms as a woman against one set of male rivals, Maria Theresa was determined not to cede authority to another set closer to home. She insisted that her power within her inherited possessions was absolute. Stollberg-Rilinger argues that even within the Holy Roman Empire, nominally her husband’s domain, it was Maria Theresa, not the emperor, who decided the direction of policy. This female primacy would be continued, with even sharper resentment on the part of the subordinated male, after Francis’s death in 1765 and the election of her eldest son, Joseph II, as his successor as Holy Roman Emperor.

Understanding this complex tangle of overlapping titles and jurisdictions is here essential. For although Maria Theresa was sovereign in her own right of the archduchy of Austria and queen of Hungary, in legal theory she ranked lower than her husband, the newly elected emperor. Yet having regained her realms as a woman against one set of male rivals, Maria Theresa was determined not to cede authority to another set closer to home. She insisted that her power within her inherited possessions was absolute. Stollberg-Rilinger argues that even within the Holy Roman Empire, nominally her husband’s domain, it was Maria Theresa, not the emperor, who decided the direction of policy. This female primacy would be continued, with even sharper resentment on the part of the subordinated male, after Francis’s death in 1765 and the election of her eldest son, Joseph II, as his successor as Holy Roman Emperor. THE HARVARD

THE HARVARD When guests used to visit Vladimir Putin in his office in the Kremlin’s Senate Palace, he’d point at the bookshelves and ask them to choose a book from Joseph Stalin’s library. Half of Stalin’s books – usually marked up by the Soviet leader himself with red or green crayons – remain in Putin’s office. As one of his ministers told me, Putin would ask the visitor to open the book and they would look together at whatever marginalia Stalin had written: sometimes it was a grim laugh: “xa-xa-xa!”; sometimes a snort of disdain: “green steam!”; at others it was just a word: “teacher” was written on the biography of Ivan the Terrible.

When guests used to visit Vladimir Putin in his office in the Kremlin’s Senate Palace, he’d point at the bookshelves and ask them to choose a book from Joseph Stalin’s library. Half of Stalin’s books – usually marked up by the Soviet leader himself with red or green crayons – remain in Putin’s office. As one of his ministers told me, Putin would ask the visitor to open the book and they would look together at whatever marginalia Stalin had written: sometimes it was a grim laugh: “xa-xa-xa!”; sometimes a snort of disdain: “green steam!”; at others it was just a word: “teacher” was written on the biography of Ivan the Terrible. Are there unrappable words? Not words that can’t be gerrymandered into rhyme by tricks of truncation or pronunciation, but words so ungainly, so unwieldy, so unhip, so unhip-hop, as to definitively resist rap’s tractor-beam powers of assimilation. Do such words exist? No! says the wide-eyed idealist in me. I mean, probably, says the grizzled skeptic, who doubts I’ll hear pulchritude or amortize or hoarfrost or chilblains dropped over a beat before I die.

Are there unrappable words? Not words that can’t be gerrymandered into rhyme by tricks of truncation or pronunciation, but words so ungainly, so unwieldy, so unhip, so unhip-hop, as to definitively resist rap’s tractor-beam powers of assimilation. Do such words exist? No! says the wide-eyed idealist in me. I mean, probably, says the grizzled skeptic, who doubts I’ll hear pulchritude or amortize or hoarfrost or chilblains dropped over a beat before I die. Intelligent decision-making doesn’t require a brain. You were capable of it before you even had one. Beginning life as a single fertilised egg, you divided and became a mass of genetically identical cells. They chattered among themselves to fashion a complex anatomical structure – your body. Even more remarkably, if you had split in two as an embryo, each half would have been able to replace what was missing, leaving you as one of two identical (monozygotic) twins. Likewise, if two mouse embryos are mushed together like a snowball, a single, normal mouse results. Just how do these embryos know what to do? We have no technology yet that has this degree of plasticity – recognising a deviation from the normal course of events and responding to achieve the same outcome overall.

Intelligent decision-making doesn’t require a brain. You were capable of it before you even had one. Beginning life as a single fertilised egg, you divided and became a mass of genetically identical cells. They chattered among themselves to fashion a complex anatomical structure – your body. Even more remarkably, if you had split in two as an embryo, each half would have been able to replace what was missing, leaving you as one of two identical (monozygotic) twins. Likewise, if two mouse embryos are mushed together like a snowball, a single, normal mouse results. Just how do these embryos know what to do? We have no technology yet that has this degree of plasticity – recognising a deviation from the normal course of events and responding to achieve the same outcome overall. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine took much of the world by surprise. It is an unprovoked and unjustified attack that will go down in history as one of the major war crimes of the 21st century, argues Noam Chomsky in the exclusive interview for Truthout that follows. Political considerations, such as those cited by Russian President Vladimir Putin, cannot be used as arguments to justify the launching of an invasion against a sovereign nation. In the face of this horrific invasion, though, the U.S. must choose urgent diplomacy over military escalation, as the latter could constitute a “death warrant for the species, with no victors,” Chomsky says.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine took much of the world by surprise. It is an unprovoked and unjustified attack that will go down in history as one of the major war crimes of the 21st century, argues Noam Chomsky in the exclusive interview for Truthout that follows. Political considerations, such as those cited by Russian President Vladimir Putin, cannot be used as arguments to justify the launching of an invasion against a sovereign nation. In the face of this horrific invasion, though, the U.S. must choose urgent diplomacy over military escalation, as the latter could constitute a “death warrant for the species, with no victors,” Chomsky says.