Tadeg Quillien in Aeon:

As a quick stroll on social media reveals, most people love showing that they are good. Whether by expressing compassion for disaster victims, sharing a post to support a social movement, or denouncing a celebrity’s racist comment, many people are eager to broadcast their high moral standing.

As a quick stroll on social media reveals, most people love showing that they are good. Whether by expressing compassion for disaster victims, sharing a post to support a social movement, or denouncing a celebrity’s racist comment, many people are eager to broadcast their high moral standing.

Critics sometimes dismiss these acts as mere ‘virtue signalling’. As the British journalist James Bartholomew (who popularised the term in a magazine article in 2015) remarks, virtue signallers enjoy the privilege of feeling better about themselves by doing very little. Unlike the kind of helping where you have to do something – help an old lady cross the street, volunteer to give meals to the dispossessed, go door-to-door to fundraise for a cause – virtue signalling often consists of completely costless actions, such as changing your profile picture or saying you don’t like a politician’s stance on immigration. Bartholomew complains that ‘saying the right things violently on Twitter is much easier than real kindness’.

Virtue signalling can be easy – but why does that make it seem bad?

More here.

One way to read this unwieldy book, with its sixty-two-page bibliography, is as a grand tour of societies from prehistory to the eighteenth century once classed by anthropologists as “primitive” according to the evolutionary model that Dawn blows to smithereens. The Kwakiutl peoples of the Northwest Coast practiced chattel slavery; their neighbors to the south in what is now California, the Yurok, did not. At Göbekli Tepe in modern Turkey, foragers erected intricately carved megaliths six thousand years before Stonehenge. The Natchez Great Sun wielded absolute power over his subjects but rarely left the Great Village, so most Natchez just stayed out of his reach. The Kwakiutl were aristocratic during winter but splintered into clan formations for the summer fishing season. Cheyenne and Lakota appointed an authoritarian police force to keep order during the buffalo hunt then dispersed into small, “anarchic” bands. The ancient Mesoamerican Olmec of present-day Mexico appear to have organized their society in part around ball games, erecting colossal stone heads depicting helmeted champions. And Chavín de Huántar in northern Peru in the first millennium BCE, with its sophisticated cut-stone architecture and monumental sculpture—well, if the authors are to be believed, it was a gigantic memory palace, a storehouse for imagistic records of shamanic journeys and hallucinogenic visions.

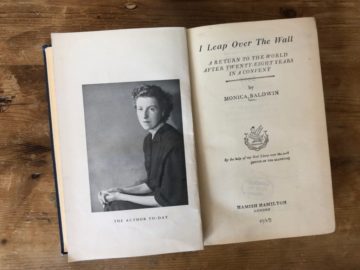

One way to read this unwieldy book, with its sixty-two-page bibliography, is as a grand tour of societies from prehistory to the eighteenth century once classed by anthropologists as “primitive” according to the evolutionary model that Dawn blows to smithereens. The Kwakiutl peoples of the Northwest Coast practiced chattel slavery; their neighbors to the south in what is now California, the Yurok, did not. At Göbekli Tepe in modern Turkey, foragers erected intricately carved megaliths six thousand years before Stonehenge. The Natchez Great Sun wielded absolute power over his subjects but rarely left the Great Village, so most Natchez just stayed out of his reach. The Kwakiutl were aristocratic during winter but splintered into clan formations for the summer fishing season. Cheyenne and Lakota appointed an authoritarian police force to keep order during the buffalo hunt then dispersed into small, “anarchic” bands. The ancient Mesoamerican Olmec of present-day Mexico appear to have organized their society in part around ball games, erecting colossal stone heads depicting helmeted champions. And Chavín de Huántar in northern Peru in the first millennium BCE, with its sophisticated cut-stone architecture and monumental sculpture—well, if the authors are to be believed, it was a gigantic memory palace, a storehouse for imagistic records of shamanic journeys and hallucinogenic visions. Ten years after Monica Baldwin voluntarily entered an enclosed religious order of Augustinian nuns, she began to think she might have made a mistake. She had entered the order on October 26, 1914, shortly after the outbreak of the World War I, when she was just twenty-one years old. At thirty-one, she hadn’t lost her faith, but she had begun to doubt her vocation; the sacrifices that cloistered life entailed did not come easily to her, and unlike many around her, she hadn’t experienced a “vital encounter” between her soul and God. Eighteen years later, she finally knew for sure: it was time to leave. Granted special dispensation from the Vatican to leave the order but remain a Roman Catholic, Baldwin—who was now forty-nine years old—quit the only adult life she’d known, that of the “strictest possible enclosure,” and emerged back into the world in 1941, into a world that had just plunged, once again, into war.

Ten years after Monica Baldwin voluntarily entered an enclosed religious order of Augustinian nuns, she began to think she might have made a mistake. She had entered the order on October 26, 1914, shortly after the outbreak of the World War I, when she was just twenty-one years old. At thirty-one, she hadn’t lost her faith, but she had begun to doubt her vocation; the sacrifices that cloistered life entailed did not come easily to her, and unlike many around her, she hadn’t experienced a “vital encounter” between her soul and God. Eighteen years later, she finally knew for sure: it was time to leave. Granted special dispensation from the Vatican to leave the order but remain a Roman Catholic, Baldwin—who was now forty-nine years old—quit the only adult life she’d known, that of the “strictest possible enclosure,” and emerged back into the world in 1941, into a world that had just plunged, once again, into war. W

W Cancer drugs usually take a scattergun approach. Chemotherapies inevitably hit healthy bystander cells while blasting tumours, sparking a slew of side effects. It is also a big ask for an anticancer drug to find and destroy an entire tumour — some are difficult to reach, or hard to penetrate once located. A long-dreamed-of alternative is to inject a battalion of tiny robots into a person with cancer. These miniature machines could navigate directly to a tumour and smartly deploy a therapeutic payload right where it is needed. “It is very difficult for drugs to penetrate through biological barriers, such as the blood–brain barrier or mucus of the gut, but a microrobot can do that,” says Wei Gao, a medical engineer at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

Cancer drugs usually take a scattergun approach. Chemotherapies inevitably hit healthy bystander cells while blasting tumours, sparking a slew of side effects. It is also a big ask for an anticancer drug to find and destroy an entire tumour — some are difficult to reach, or hard to penetrate once located. A long-dreamed-of alternative is to inject a battalion of tiny robots into a person with cancer. These miniature machines could navigate directly to a tumour and smartly deploy a therapeutic payload right where it is needed. “It is very difficult for drugs to penetrate through biological barriers, such as the blood–brain barrier or mucus of the gut, but a microrobot can do that,” says Wei Gao, a medical engineer at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. I have been doing a great deal of publicity these past weeks for my new book,

I have been doing a great deal of publicity these past weeks for my new book,  The

The  Over the years, I’ve read quite a few books about the brain, most of them written by academic neuroscientists who view it through the lens of sophisticated lab experiments. Recently, I picked up a brain book that’s much more theoretical. It’s called A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence, by a tech entrepreneur named Jeff Hawkins.

Over the years, I’ve read quite a few books about the brain, most of them written by academic neuroscientists who view it through the lens of sophisticated lab experiments. Recently, I picked up a brain book that’s much more theoretical. It’s called A Thousand Brains: A New Theory of Intelligence, by a tech entrepreneur named Jeff Hawkins. R

R In 2017, Karen Kostroff, a renowned oncology surgeon at Northwell Health in the New York Metropolitan area added a new talking point to her standard conversation with breast cancer patients facing tumor removal surgery. These conversations are never easy, because a cancer diagnosis is devastating news. But the new topic seemed to give her patients a sense of purpose, a feeling that their medical misfortune had the potential to do something good for other people.

In 2017, Karen Kostroff, a renowned oncology surgeon at Northwell Health in the New York Metropolitan area added a new talking point to her standard conversation with breast cancer patients facing tumor removal surgery. These conversations are never easy, because a cancer diagnosis is devastating news. But the new topic seemed to give her patients a sense of purpose, a feeling that their medical misfortune had the potential to do something good for other people.  Alex Kane in Jewish Currents:

Alex Kane in Jewish Currents: