Elizabeth Pain in Science:

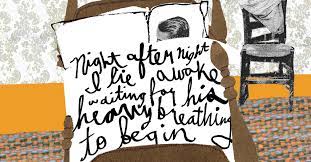

It’s common for graduate students to feel overwhelmed, frustrated, and burned out. But as social scientist Sharon Mallon neared the end of her Ph.D., she also felt emotionally drained by her research topic: suicide. The work felt intensely important, but she soon found that conducting sensitive interviews and synthesizing what she learned took a toll on her mental health.

One day, desperately needing a break, she rented two movies from a video shop. As she put on the first, a suicide scene burst onto the screen. She immediately stopped watching and put on the second, only to be confronted with another suicide scene halfway through. “I wanted to distract myself from this topic, but here it is, following me,” Mallon recalls. A few months later, she got to the point “where I just thought, ‘I’m going to drop out; I can’t do this.’”

Many scientists, like Mallon, work on topics that have the potential to be personally upsetting—for instance, wildlife biologists who study endangered species and health researchers who study devastating diseases. Working in such fields can give researchers a strong sense of purpose, but the emotional challenges can also make an already arduous job even more difficult. Science Careers spoke with three researchers who have experienced these challenges to find out how they deal with the emotional toll.

More here.

In thinking about technology, three questions are fundamental. What is technology for? What are we for? And how is our answer to the first question related to our answer to the second?

In thinking about technology, three questions are fundamental. What is technology for? What are we for? And how is our answer to the first question related to our answer to the second? The health workers try to explain to Dolhare that his relative succumbed to Covid-19, and that he, too, should be inoculated to protect himself from infection. “But how will I get corona if it doesn’t exist?” he asks, repeating the false claim.

The health workers try to explain to Dolhare that his relative succumbed to Covid-19, and that he, too, should be inoculated to protect himself from infection. “But how will I get corona if it doesn’t exist?” he asks, repeating the false claim. For years, I played basketball with a humanities skeptic. He was an endowment manager at the Ivy League university from which he had graduated with a degree in economics. He knew I was a professor of literature, and one day he asked what I taught—and did I by any chance teach Moby-Dick? I nodded, and he said, “You don’t believe the hype, do you?” His proudest moment in college had come when, required to read the novel for a first-year class, he developed a firm belief that Moby-Dick’s reputation was explainable chiefly by its obscurity. The emperor had no clothes: The novel was taught because it was revered, and revered because it was taught. Baffled readers took their incomprehension as a sign of its elusive greatness. Teachers followed blind tradition and enjoyed the aura of solemn stupefaction.

For years, I played basketball with a humanities skeptic. He was an endowment manager at the Ivy League university from which he had graduated with a degree in economics. He knew I was a professor of literature, and one day he asked what I taught—and did I by any chance teach Moby-Dick? I nodded, and he said, “You don’t believe the hype, do you?” His proudest moment in college had come when, required to read the novel for a first-year class, he developed a firm belief that Moby-Dick’s reputation was explainable chiefly by its obscurity. The emperor had no clothes: The novel was taught because it was revered, and revered because it was taught. Baffled readers took their incomprehension as a sign of its elusive greatness. Teachers followed blind tradition and enjoyed the aura of solemn stupefaction. A reader who opens a volume of Šalamun to any page is likely to find a startling line: “Bees rustle like a fifth column”; “I am a volcano that needs no sandals.” His images cascade in bewildering but thrilling torrents: “Wreaths shut in butter, shut in a glassy / casket in the hydra’s snout under the tree-tooth, / left shadow, microbes, blown up by / Job, flushed tender shivering gelatinous / Law morphing into socage.” Tonally, he can shift abruptly from the silly (“the soul of earth jacks off the skeleton key”) to the breathtaking (“My heart / beats like the heart of a hare who will die of fear”). He is a poet of wild and strange delights; to love Šalamun, readers must want to be invited into uncharted territory.

A reader who opens a volume of Šalamun to any page is likely to find a startling line: “Bees rustle like a fifth column”; “I am a volcano that needs no sandals.” His images cascade in bewildering but thrilling torrents: “Wreaths shut in butter, shut in a glassy / casket in the hydra’s snout under the tree-tooth, / left shadow, microbes, blown up by / Job, flushed tender shivering gelatinous / Law morphing into socage.” Tonally, he can shift abruptly from the silly (“the soul of earth jacks off the skeleton key”) to the breathtaking (“My heart / beats like the heart of a hare who will die of fear”). He is a poet of wild and strange delights; to love Šalamun, readers must want to be invited into uncharted territory. Owen Hatherley blithely claims that this massive tour de force is ‘a guide to the place … you’re visiting, or a place you want to visit’. Pull the other one, squire. The notion of Owen Hatherley, Tripadvisor, is sheerly preposterous, though it may appeal to a tremulous publisher figuring out how to market this behemoth. He is really a polemicist, ready to take issue with anyone, including himself. His insistent invitations to look are heavy with allusions, catholic comparisons and quiet asides. The result of his tireless labour is an oblique, partial, lopsided survey of Britain throughout the long modernist century; and no matter what a platoon of celluloid collars and triple-breasted waistcoats may have wished for, modernism did triumph, in many guises. Its variety goes unnoticed by its antagonists, who have no ability to discern the kinship of much modernist architecture to its medieval and Victorian precursors. What they do have, in abundance, is torpid prejudice. This approximate gazetteer will not convince the obstinate to change their minds. But that really is not its point. It is a gorgeous treat for the already converted and, maybe, for those impaled on the spikes of equivocation. Hatherley’s only historical blunder is to describe Art Nouveau as ‘a mechanized sub-species of the Arts and Crafts’. The latter was pretty much exclusively English; the former was its flashy contemporary in places such as Belgium, Catalonia and Nancy. They hardly infected each other.

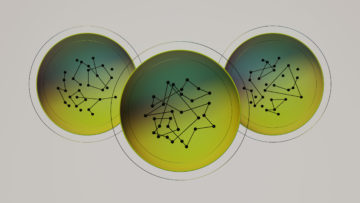

Owen Hatherley blithely claims that this massive tour de force is ‘a guide to the place … you’re visiting, or a place you want to visit’. Pull the other one, squire. The notion of Owen Hatherley, Tripadvisor, is sheerly preposterous, though it may appeal to a tremulous publisher figuring out how to market this behemoth. He is really a polemicist, ready to take issue with anyone, including himself. His insistent invitations to look are heavy with allusions, catholic comparisons and quiet asides. The result of his tireless labour is an oblique, partial, lopsided survey of Britain throughout the long modernist century; and no matter what a platoon of celluloid collars and triple-breasted waistcoats may have wished for, modernism did triumph, in many guises. Its variety goes unnoticed by its antagonists, who have no ability to discern the kinship of much modernist architecture to its medieval and Victorian precursors. What they do have, in abundance, is torpid prejudice. This approximate gazetteer will not convince the obstinate to change their minds. But that really is not its point. It is a gorgeous treat for the already converted and, maybe, for those impaled on the spikes of equivocation. Hatherley’s only historical blunder is to describe Art Nouveau as ‘a mechanized sub-species of the Arts and Crafts’. The latter was pretty much exclusively English; the former was its flashy contemporary in places such as Belgium, Catalonia and Nancy. They hardly infected each other. Infectious diseases such as malaria remain a leading cause of death in many regions. This is partly because people there don’t have access to medical diagnostic tools that can detect these diseases (along with a range of non-infectious diseases) at an early stage, when there is more scope for treatment. It’s a challenge scientists have risen to, with a goal to democratize

Infectious diseases such as malaria remain a leading cause of death in many regions. This is partly because people there don’t have access to medical diagnostic tools that can detect these diseases (along with a range of non-infectious diseases) at an early stage, when there is more scope for treatment. It’s a challenge scientists have risen to, with a goal to democratize  In 2013, the French economist Thomas Piketty, in his best seller “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” a book eagerly received in the wake of the 2008 economic collapse, put forth the notion that returns on capital historically outstrip economic growth (his famous r>g formula). The upshot? The rich get richer, while the rest of us stay stuck in the mud. Now, nearly a decade later, Piketty is set to publish “A Brief History of Equality,” in which he argues that we’re on a trajectory of greater, not less, equality and lays out his prescriptions for remedying our current corrosive wealth disparities. (In short: Tax the rich.) If the line from one book to the other looks slightly askew given the state of the world, then, Piketty suggests, you’re looking from the wrong vantage point. “I am relatively optimistic,” says Piketty, who is 50, “about the fact that there is a long-run movement toward more equality, which goes beyond the little details of what happens within a specific decade.”

In 2013, the French economist Thomas Piketty, in his best seller “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” a book eagerly received in the wake of the 2008 economic collapse, put forth the notion that returns on capital historically outstrip economic growth (his famous r>g formula). The upshot? The rich get richer, while the rest of us stay stuck in the mud. Now, nearly a decade later, Piketty is set to publish “A Brief History of Equality,” in which he argues that we’re on a trajectory of greater, not less, equality and lays out his prescriptions for remedying our current corrosive wealth disparities. (In short: Tax the rich.) If the line from one book to the other looks slightly askew given the state of the world, then, Piketty suggests, you’re looking from the wrong vantage point. “I am relatively optimistic,” says Piketty, who is 50, “about the fact that there is a long-run movement toward more equality, which goes beyond the little details of what happens within a specific decade.” If Sir Kingsley Amis was still alive today, on the occasion of his centenary — an event that would owe a quite remarkable amount to medical science, and might, given the context of this particular weekend, even be seen as a second Resurrection narrative — he might be amused by the way that he has been treated by posterity. I’ve written about the decline in Kingers’ fortunes, justified or not, for the May issue of The Critic, but one area that I was only able to touch on in the most passing of fashions was one that many Amis aficionados prefer not to dwell on. Yes — oh dear yes — Kingsley Amis wrote poetry. Many may have wished that it were not so.

If Sir Kingsley Amis was still alive today, on the occasion of his centenary — an event that would owe a quite remarkable amount to medical science, and might, given the context of this particular weekend, even be seen as a second Resurrection narrative — he might be amused by the way that he has been treated by posterity. I’ve written about the decline in Kingers’ fortunes, justified or not, for the May issue of The Critic, but one area that I was only able to touch on in the most passing of fashions was one that many Amis aficionados prefer not to dwell on. Yes — oh dear yes — Kingsley Amis wrote poetry. Many may have wished that it were not so. Well Rick B. from the United States, it seems that you did not like the Norwegian director Joachim Trier’s newest film The Worst Person in The World very much. Your Amazon review is quite short, and pretty rough. You gave it one star. The title of your review is “tedious, annoying people talking too much.” And then you followed that up with two words and an exclamation mark: “It sucks!”

Well Rick B. from the United States, it seems that you did not like the Norwegian director Joachim Trier’s newest film The Worst Person in The World very much. Your Amazon review is quite short, and pretty rough. You gave it one star. The title of your review is “tedious, annoying people talking too much.” And then you followed that up with two words and an exclamation mark: “It sucks!” When the mathematicians

When the mathematicians  Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the next technological revolution, a breakthrough that poses both great risks and great rewards for human rights. Our ability to mitigate AI’s risks will depend not on its technical features, but on how and why those features are used. A hammer can build a house or break a skull — the impact of any tool depends on who wields it, their intentions behind its use, and what constraints, if any, have been built around the tool’s use.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the next technological revolution, a breakthrough that poses both great risks and great rewards for human rights. Our ability to mitigate AI’s risks will depend not on its technical features, but on how and why those features are used. A hammer can build a house or break a skull — the impact of any tool depends on who wields it, their intentions behind its use, and what constraints, if any, have been built around the tool’s use. Creativity is an essential element of the human condition. Yet unlike other elements of our humanity, there’s a perception that creativity seems to leave us as we age. Children, wrapped up in their imaginary play worlds and projects, are notoriously unhindered in their creativity. But adults are far less adept at conjuring the fantastical and bizarre imagination that their childhood selves had easy access to. Many adults long for those playful youthful days, when conjuring up a grand scene, on paper or on the playground, was as natural as breathing.

Creativity is an essential element of the human condition. Yet unlike other elements of our humanity, there’s a perception that creativity seems to leave us as we age. Children, wrapped up in their imaginary play worlds and projects, are notoriously unhindered in their creativity. But adults are far less adept at conjuring the fantastical and bizarre imagination that their childhood selves had easy access to. Many adults long for those playful youthful days, when conjuring up a grand scene, on paper or on the playground, was as natural as breathing. Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950) was once the most famous poet in America. Her collections sold tens of thousands of copies, and her readings filled theaters from New York to Texas. She was the female voice of the Jazz Age, the New Woman incarnate whose passionate and iconoclastic verse earned her a devoted following. Her 1920 poem “First Fig” became an anthem for a generation tired of Victorian mores:

Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892-1950) was once the most famous poet in America. Her collections sold tens of thousands of copies, and her readings filled theaters from New York to Texas. She was the female voice of the Jazz Age, the New Woman incarnate whose passionate and iconoclastic verse earned her a devoted following. Her 1920 poem “First Fig” became an anthem for a generation tired of Victorian mores: