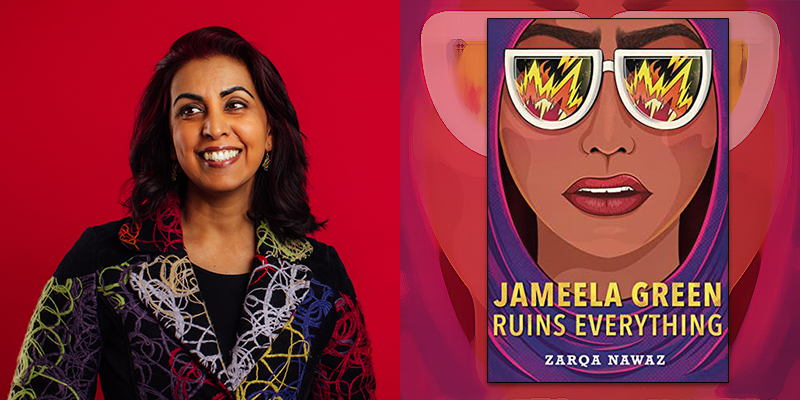

Molly Odintz in Crime Reads:

Molly Odintz: The premise for this novel is wildly inventive. What was your inspiration?

Zarqa Nawaz: When my memoir, Laughing All the Way to the Mosque, didn’t make it to the New York Times Best Seller list, I became a little cynical towards life. It was 2014 and ISIS had just emerged and was dominating the headlines. Muslims are forever fighting the PR war when it comes to their image. Political pundits were opining that radical Islamic jihadists were the norm in Muslim culture. I knew there was a deeper story behind ISIS, especially from the one the media was portraying. I started doing research and the novel began to emerge—a bitter writer, reeling from professional failure, gets embroiled in an ISIS like group and a series of unfortunate events ensue.

Zarqa Nawaz: When my memoir, Laughing All the Way to the Mosque, didn’t make it to the New York Times Best Seller list, I became a little cynical towards life. It was 2014 and ISIS had just emerged and was dominating the headlines. Muslims are forever fighting the PR war when it comes to their image. Political pundits were opining that radical Islamic jihadists were the norm in Muslim culture. I knew there was a deeper story behind ISIS, especially from the one the media was portraying. I started doing research and the novel began to emerge—a bitter writer, reeling from professional failure, gets embroiled in an ISIS like group and a series of unfortunate events ensue.

More here.

A study looking at the economic lifetimes of 61 commercially used metals finds that more than half have a lifespan of less than 10 years. The research, published on 19 May in Nature Sustainability

A study looking at the economic lifetimes of 61 commercially used metals finds that more than half have a lifespan of less than 10 years. The research, published on 19 May in Nature Sustainability Depending on one’s pace, the season, and the ongoing state of war, it is a day’s hike from Andarab to the border of legendary Panjshir, the adjacent province in the highlands of Afghanistan. The two mountain districts, part of a five-hundred-mile-long stretch of the Hindu Kush extending from the Himalayas, are citadels that have rained doom on every bully ever to pass through Central Asia in endless dogged pursuit of cruelty and loot.

Depending on one’s pace, the season, and the ongoing state of war, it is a day’s hike from Andarab to the border of legendary Panjshir, the adjacent province in the highlands of Afghanistan. The two mountain districts, part of a five-hundred-mile-long stretch of the Hindu Kush extending from the Himalayas, are citadels that have rained doom on every bully ever to pass through Central Asia in endless dogged pursuit of cruelty and loot. May, a month we traditionally associate with spring, Mother’s Day, and graduations, was defined this year by a far different rite: funerals. In a single ten-day stretch, forty-four people were murdered in mass shootings throughout the country—a carnival of violence that confirmed, among other things, the political cowardice of a large portion of our elected leadership, the thin pretense of our moral credibility, and the sham of public displays of sympathy that translate into no actual changes in our laws, our culture, or our murderous propensities. In the two deadliest of these incidents, the oldest victim was an eighty-six-year-old grandmother, who was shot in a Tops supermarket in Buffalo, New York; the youngest were nine-year-old fourth-grade students, who died in connected classrooms at Robb Elementary School, in Uvalde, Texas.

May, a month we traditionally associate with spring, Mother’s Day, and graduations, was defined this year by a far different rite: funerals. In a single ten-day stretch, forty-four people were murdered in mass shootings throughout the country—a carnival of violence that confirmed, among other things, the political cowardice of a large portion of our elected leadership, the thin pretense of our moral credibility, and the sham of public displays of sympathy that translate into no actual changes in our laws, our culture, or our murderous propensities. In the two deadliest of these incidents, the oldest victim was an eighty-six-year-old grandmother, who was shot in a Tops supermarket in Buffalo, New York; the youngest were nine-year-old fourth-grade students, who died in connected classrooms at Robb Elementary School, in Uvalde, Texas. In a sense, writing a book is easy. You just keep putting one interesting sentence after another, then thread them all together along a more or less fine narrative line. Only, it isn’t easy – in fact, it’s famously difficult, a daunting and arduous labour that can frequently leave you in a state of utter nervous exhaustion, reaching for the bottle or the pills. Since his creative breakthrough with

In a sense, writing a book is easy. You just keep putting one interesting sentence after another, then thread them all together along a more or less fine narrative line. Only, it isn’t easy – in fact, it’s famously difficult, a daunting and arduous labour that can frequently leave you in a state of utter nervous exhaustion, reaching for the bottle or the pills. Since his creative breakthrough with  Gregory Brew in Phenomenal World:

Gregory Brew in Phenomenal World: Columbine. Parkland. Pulse. Virginia Tech. Sandy Hook. Las Vegas.

Columbine. Parkland. Pulse. Virginia Tech. Sandy Hook. Las Vegas. Researchers studying human remains from Pompeii have extracted genetic secrets from the bones of a man and a woman who were buried when the Roman city was engulfed in volcanic ash.

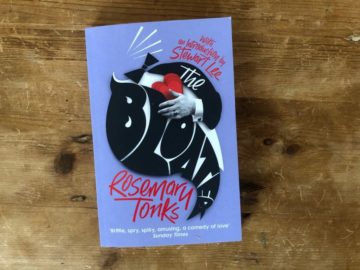

Researchers studying human remains from Pompeii have extracted genetic secrets from the bones of a man and a woman who were buried when the Roman city was engulfed in volcanic ash. The poet and novelist Rosemary Tonks wrote her third novel, The Bloater, in just four weeks in the autumn of 1967, which would have been impressive by any standards but her own. She had originally set out to finish it in half the time and had hoped it would earn her “a lot of red-hot money.” (Here, she fell short too). But the result was a dizzying, madcap story that was a hit with the critics. Again, most writers would have been over the moon with such a reception, but Tonks could never be so predictable. “It just proves the English like their porridge,” she once reportedly replied to congratulations from her editor. To borrow a confession from The Bloater’s canny narrator—a young woman who bears more than a passing resemblance to Tonks herself: “I knew perfectly well what I was doing.”

The poet and novelist Rosemary Tonks wrote her third novel, The Bloater, in just four weeks in the autumn of 1967, which would have been impressive by any standards but her own. She had originally set out to finish it in half the time and had hoped it would earn her “a lot of red-hot money.” (Here, she fell short too). But the result was a dizzying, madcap story that was a hit with the critics. Again, most writers would have been over the moon with such a reception, but Tonks could never be so predictable. “It just proves the English like their porridge,” she once reportedly replied to congratulations from her editor. To borrow a confession from The Bloater’s canny narrator—a young woman who bears more than a passing resemblance to Tonks herself: “I knew perfectly well what I was doing.” When you get into a car with John Waters, the infamous filmmaker behind transgressive classics such as “Pink Flamingos,” “

When you get into a car with John Waters, the infamous filmmaker behind transgressive classics such as “Pink Flamingos,” “ SPEAKING AT HARVARD LAW SCHOOL’S

SPEAKING AT HARVARD LAW SCHOOL’S