Maria Popova at The Marginalian:

A person is a perpetual ongoingness perpetually mistaking itself for a still point. We call this figment personality or identity or self, and yet we are constantly making and remaking ourselves. Composing a life as the pages of time keep turning is the great creative act we are here for. Like evolution, like Leaves of Grass, it is the work of continual revision, not toward greater perfection but toward greater authenticity, which is at bottom the adaptation of the self to the soul and the soul to the world.

A person is a perpetual ongoingness perpetually mistaking itself for a still point. We call this figment personality or identity or self, and yet we are constantly making and remaking ourselves. Composing a life as the pages of time keep turning is the great creative act we are here for. Like evolution, like Leaves of Grass, it is the work of continual revision, not toward greater perfection but toward greater authenticity, which is at bottom the adaptation of the self to the soul and the soul to the world.

In one of the essays found in his exquisite 1877 collection Birds and Poets (public library | public domain), the philosopher-naturalist John Burroughs (April 3, 1837–March 29, 1921) explores the nature of that creative act through a parallel between poetry and personhood anchored in a brilliant metaphor for the two different approaches to creation. He writes:

There are in nature two types or forms, the cell and the crystal. One means the organic, the other inorganic; one means growth, development, life; the other means reaction, solidification, rest. The hint and model of all creative works is the cell; critical, reflective, and philosophical works are nearer akin to the crystal; while there is much good literature that is neither the one nor the other distinctively, but which in a measure touches and includes both.

more here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

The

The  “Little Reunions ought to be burned,” Eileen Chang wrote to her friend and literary executor, Stephen Soong, in 1976, the year she finished what would be her last novel. When it was finally published, in 2009, fourteen years after her death, Little Reunions seemed to carry this curse with it; the book received widespread criticism for its cryptic narrative and for not sounding like Eileen Chang.

“Little Reunions ought to be burned,” Eileen Chang wrote to her friend and literary executor, Stephen Soong, in 1976, the year she finished what would be her last novel. When it was finally published, in 2009, fourteen years after her death, Little Reunions seemed to carry this curse with it; the book received widespread criticism for its cryptic narrative and for not sounding like Eileen Chang. In “Super Natural,” award-winning science writer Alex Riley casts his inquisitive, generous gaze upon the extremists. No, not the far right or the far left; these are the far-deep, far-up, and far-flung life-forms that inhabit Earth’s less move-in-ready biomes. From snailfish and wood frogs to painted turtles and tardigrades, these remarkable creatures display a knack for thriving – or at least carrying on – in a niche of their own. Mr. Riley chatted via video with Monitor contributor Erin Douglass about the marvels and possibilities of such lives on the edge. The interview has been edited and condensed.

In “Super Natural,” award-winning science writer Alex Riley casts his inquisitive, generous gaze upon the extremists. No, not the far right or the far left; these are the far-deep, far-up, and far-flung life-forms that inhabit Earth’s less move-in-ready biomes. From snailfish and wood frogs to painted turtles and tardigrades, these remarkable creatures display a knack for thriving – or at least carrying on – in a niche of their own. Mr. Riley chatted via video with Monitor contributor Erin Douglass about the marvels and possibilities of such lives on the edge. The interview has been edited and condensed. In 1983, the octogenarian geneticist Barbara McClintock stood at the lectern of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. She was famously publicity averse — nearly a hermit — but it’s customary for people to speak when they’re awarded a Nobel Prize, so she delivered a halting account of the experiments that had led to her discovery, in the early 1950s, of how DNA sequences can relocate across the genome. Near the end of the speech, blinking through wire-framed glasses, she changed the subject, asking: “What does a cell know of itself?”

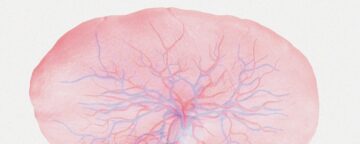

In 1983, the octogenarian geneticist Barbara McClintock stood at the lectern of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. She was famously publicity averse — nearly a hermit — but it’s customary for people to speak when they’re awarded a Nobel Prize, so she delivered a halting account of the experiments that had led to her discovery, in the early 1950s, of how DNA sequences can relocate across the genome. Near the end of the speech, blinking through wire-framed glasses, she changed the subject, asking: “What does a cell know of itself?” The next time you get a blood test, X-ray,

The next time you get a blood test, X-ray,  Getting along in society requires that we mostly adhere to certainly shared norms and customs. Often it’s not enough that we all know what the rules are, but also that everyone else knows the rules, and that they know that we know the rules, and so on. Philosophers and game theorists refer to this as

Getting along in society requires that we mostly adhere to certainly shared norms and customs. Often it’s not enough that we all know what the rules are, but also that everyone else knows the rules, and that they know that we know the rules, and so on. Philosophers and game theorists refer to this as  After epidemiologists linked typhoid outbreaks to water cleanliness, cities began building large-scale sand filtration systems in the 1890s, and in 1908, Jersey City pioneered the first continuous chlorination of a public water supply. By the 1920s, typhoid deaths had fallen by two-thirds, and waterborne diseases were in retreat across the country.

After epidemiologists linked typhoid outbreaks to water cleanliness, cities began building large-scale sand filtration systems in the 1890s, and in 1908, Jersey City pioneered the first continuous chlorination of a public water supply. By the 1920s, typhoid deaths had fallen by two-thirds, and waterborne diseases were in retreat across the country. The world needs a new economics for neglected places – for those who have fallen behind others in the same country, whether it be a rich one or a poor one. The place in question might be a community, a town, or a region: Muslims in France, Rotherham in Northern England, or Colombia’s Atlantic-Caribbean coastal region.

The world needs a new economics for neglected places – for those who have fallen behind others in the same country, whether it be a rich one or a poor one. The place in question might be a community, a town, or a region: Muslims in France, Rotherham in Northern England, or Colombia’s Atlantic-Caribbean coastal region. This past summer, I was surprised to encounter a face I knew in two most unexpected places. The first was in a photo montage accompanying an article written by Josh Kovensky of Talking Points Memo in the wake of J.D. Vance becoming the Vice Presidential nominee, entitled “A Journey Through the Authoritarian Right.” Arranged in the collage among images of a ripped man with lasers shooting from his eyes, of anti-democracy blogger Curtis Yarvin, and of Peter Thiel rubbing Benjamins between his thumb and forefinger, was my former professor and friend from Stanford University, René Girard. I was in France at the time; mere hours after reading Kovensky’s piece, I saw through the window of a taxi René’s face again—this time in the form of a larger-than-life decal on a light rail car in Avignon, where as it happens he is one of a dozen local heroes permanently celebrated on the new transit system. What do the medieval, culturally-rich, Provençal city of Avignon and the American authoritarian right have in common? Both claim a bond with this influential philosopher and member of L’Académie Française, who died in 2015. Only one of the claims is legitimate. The misappropriation of Girard’s ideas by the American right is not just a matter of academic concern; it has significant implications for our political discourse and society.

This past summer, I was surprised to encounter a face I knew in two most unexpected places. The first was in a photo montage accompanying an article written by Josh Kovensky of Talking Points Memo in the wake of J.D. Vance becoming the Vice Presidential nominee, entitled “A Journey Through the Authoritarian Right.” Arranged in the collage among images of a ripped man with lasers shooting from his eyes, of anti-democracy blogger Curtis Yarvin, and of Peter Thiel rubbing Benjamins between his thumb and forefinger, was my former professor and friend from Stanford University, René Girard. I was in France at the time; mere hours after reading Kovensky’s piece, I saw through the window of a taxi René’s face again—this time in the form of a larger-than-life decal on a light rail car in Avignon, where as it happens he is one of a dozen local heroes permanently celebrated on the new transit system. What do the medieval, culturally-rich, Provençal city of Avignon and the American authoritarian right have in common? Both claim a bond with this influential philosopher and member of L’Académie Française, who died in 2015. Only one of the claims is legitimate. The misappropriation of Girard’s ideas by the American right is not just a matter of academic concern; it has significant implications for our political discourse and society. N

N P

P