Shiri Pasternak in Boston Review:

I learned my name was on the list from a Jewish colleague at my university, a woman I hardly know. “I need to tell you something,” she wrote in an email to me. “Do you have a minute for a call today?” A local Facebook group with 47,000 followers, I learned, had posted a list of “Self Hating Jews that are seeking the destruction of our community.” They called it the “kapo list,” a term for Nazi collaborators in the concentration camps that, as of late, has been repurposed to censure Jewish critics of Israel. A few weeks later, I was on a new list: “[trash can icon] Jews.” It was populated with the names of Jewish people who had deputed at the local school board on a report that conflated antisemitism with anti-Zionism. The lister bragged that they had reported us to the Israeli Embassy. This time, several people awkwardly reached out to me: “I saw the list.” It must have gotten around.

The lists I was put on were aimed at anti-Zionist Jews, seeking to police the internal party line by defining them as traitors for speaking out on Israel. But they are long predated by other lists—namely, lists of Palestinians, Arabs, and Muslims that target the right to tell their histories, organize, and share analysis of Palestine. And though these lists vary in their targets and tactics, they all share a common end: to intimidate the movement for Palestinian rights into silence by denigrating its advocates to the point where their livelihoods and mobility are threatened.

More here.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

In “Super Natural,” award-winning science writer Alex Riley casts his inquisitive, generous gaze upon the extremists. No, not the far right or the far left; these are the far-deep, far-up, and far-flung life-forms that inhabit Earth’s less move-in-ready biomes. From snailfish and wood frogs to painted turtles and tardigrades, these remarkable creatures display a knack for thriving – or at least carrying on – in a niche of their own. Mr. Riley chatted via video with Monitor contributor Erin Douglass about the marvels and possibilities of such lives on the edge. The interview has been edited and condensed.

In “Super Natural,” award-winning science writer Alex Riley casts his inquisitive, generous gaze upon the extremists. No, not the far right or the far left; these are the far-deep, far-up, and far-flung life-forms that inhabit Earth’s less move-in-ready biomes. From snailfish and wood frogs to painted turtles and tardigrades, these remarkable creatures display a knack for thriving – or at least carrying on – in a niche of their own. Mr. Riley chatted via video with Monitor contributor Erin Douglass about the marvels and possibilities of such lives on the edge. The interview has been edited and condensed. In 1983, the octogenarian geneticist Barbara McClintock stood at the lectern of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. She was famously publicity averse — nearly a hermit — but it’s customary for people to speak when they’re awarded a Nobel Prize, so she delivered a halting account of the experiments that had led to her discovery, in the early 1950s, of how DNA sequences can relocate across the genome. Near the end of the speech, blinking through wire-framed glasses, she changed the subject, asking: “What does a cell know of itself?”

In 1983, the octogenarian geneticist Barbara McClintock stood at the lectern of the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm. She was famously publicity averse — nearly a hermit — but it’s customary for people to speak when they’re awarded a Nobel Prize, so she delivered a halting account of the experiments that had led to her discovery, in the early 1950s, of how DNA sequences can relocate across the genome. Near the end of the speech, blinking through wire-framed glasses, she changed the subject, asking: “What does a cell know of itself?” The next time you get a blood test, X-ray,

The next time you get a blood test, X-ray,  Getting along in society requires that we mostly adhere to certainly shared norms and customs. Often it’s not enough that we all know what the rules are, but also that everyone else knows the rules, and that they know that we know the rules, and so on. Philosophers and game theorists refer to this as

Getting along in society requires that we mostly adhere to certainly shared norms and customs. Often it’s not enough that we all know what the rules are, but also that everyone else knows the rules, and that they know that we know the rules, and so on. Philosophers and game theorists refer to this as  After epidemiologists linked typhoid outbreaks to water cleanliness, cities began building large-scale sand filtration systems in the 1890s, and in 1908, Jersey City pioneered the first continuous chlorination of a public water supply. By the 1920s, typhoid deaths had fallen by two-thirds, and waterborne diseases were in retreat across the country.

After epidemiologists linked typhoid outbreaks to water cleanliness, cities began building large-scale sand filtration systems in the 1890s, and in 1908, Jersey City pioneered the first continuous chlorination of a public water supply. By the 1920s, typhoid deaths had fallen by two-thirds, and waterborne diseases were in retreat across the country. The world needs a new economics for neglected places – for those who have fallen behind others in the same country, whether it be a rich one or a poor one. The place in question might be a community, a town, or a region: Muslims in France, Rotherham in Northern England, or Colombia’s Atlantic-Caribbean coastal region.

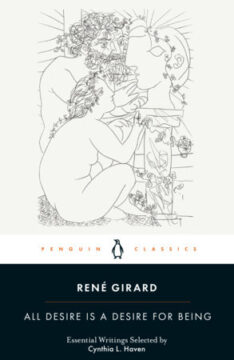

The world needs a new economics for neglected places – for those who have fallen behind others in the same country, whether it be a rich one or a poor one. The place in question might be a community, a town, or a region: Muslims in France, Rotherham in Northern England, or Colombia’s Atlantic-Caribbean coastal region. This past summer, I was surprised to encounter a face I knew in two most unexpected places. The first was in a photo montage accompanying an article written by Josh Kovensky of Talking Points Memo in the wake of J.D. Vance becoming the Vice Presidential nominee, entitled “A Journey Through the Authoritarian Right.” Arranged in the collage among images of a ripped man with lasers shooting from his eyes, of anti-democracy blogger Curtis Yarvin, and of Peter Thiel rubbing Benjamins between his thumb and forefinger, was my former professor and friend from Stanford University, René Girard. I was in France at the time; mere hours after reading Kovensky’s piece, I saw through the window of a taxi René’s face again—this time in the form of a larger-than-life decal on a light rail car in Avignon, where as it happens he is one of a dozen local heroes permanently celebrated on the new transit system. What do the medieval, culturally-rich, Provençal city of Avignon and the American authoritarian right have in common? Both claim a bond with this influential philosopher and member of L’Académie Française, who died in 2015. Only one of the claims is legitimate. The misappropriation of Girard’s ideas by the American right is not just a matter of academic concern; it has significant implications for our political discourse and society.

This past summer, I was surprised to encounter a face I knew in two most unexpected places. The first was in a photo montage accompanying an article written by Josh Kovensky of Talking Points Memo in the wake of J.D. Vance becoming the Vice Presidential nominee, entitled “A Journey Through the Authoritarian Right.” Arranged in the collage among images of a ripped man with lasers shooting from his eyes, of anti-democracy blogger Curtis Yarvin, and of Peter Thiel rubbing Benjamins between his thumb and forefinger, was my former professor and friend from Stanford University, René Girard. I was in France at the time; mere hours after reading Kovensky’s piece, I saw through the window of a taxi René’s face again—this time in the form of a larger-than-life decal on a light rail car in Avignon, where as it happens he is one of a dozen local heroes permanently celebrated on the new transit system. What do the medieval, culturally-rich, Provençal city of Avignon and the American authoritarian right have in common? Both claim a bond with this influential philosopher and member of L’Académie Française, who died in 2015. Only one of the claims is legitimate. The misappropriation of Girard’s ideas by the American right is not just a matter of academic concern; it has significant implications for our political discourse and society. N

N P

P At the blow of a whistle, each dog, one at a time, was let out onto the grounds and on its doggy way, snuffling the grooves and crevices of the obstacle course in the hunt for a swab doused in an herbal essential oil. The dogs moved evenly, steady as magnetic north, until they appealed to their handlers with glances that functioned like code. This dogsperanto—a language of punctuation marks, canine body cues in expressions of “?” or “!”—met human encouragement in a surrealist covenant between trainer and trainee. Woof begat nod, nod begat pursuit. The lagotto came to a halt at a traffic cone.

At the blow of a whistle, each dog, one at a time, was let out onto the grounds and on its doggy way, snuffling the grooves and crevices of the obstacle course in the hunt for a swab doused in an herbal essential oil. The dogs moved evenly, steady as magnetic north, until they appealed to their handlers with glances that functioned like code. This dogsperanto—a language of punctuation marks, canine body cues in expressions of “?” or “!”—met human encouragement in a surrealist covenant between trainer and trainee. Woof begat nod, nod begat pursuit. The lagotto came to a halt at a traffic cone. T

T Between 17 January 2023 and 19 August 2024, María Branyas Morera, of Spain, was officially the

Between 17 January 2023 and 19 August 2024, María Branyas Morera, of Spain, was officially the