Category: Recommended Reading

The Polarization Spiral

Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff in Persuasion:

As probably will surprise no one, the polarization spiral between the left and the right has only gotten more intense in the last three years. Most alarming is the growing acceptance of political violence as a justifiable method for achieving political goals. A survey in 2019 found that approximately one-fifth of partisans in both parties believed that violence against the opposing party would be at least “a little” justified if their party lost the 2020 election. Between 2020 and 2021 the share of students surveyed who said violent protest was “never acceptable” dropped from 82% to 76% and at most elite schools it was even lower.

As probably will surprise no one, the polarization spiral between the left and the right has only gotten more intense in the last three years. Most alarming is the growing acceptance of political violence as a justifiable method for achieving political goals. A survey in 2019 found that approximately one-fifth of partisans in both parties believed that violence against the opposing party would be at least “a little” justified if their party lost the 2020 election. Between 2020 and 2021 the share of students surveyed who said violent protest was “never acceptable” dropped from 82% to 76% and at most elite schools it was even lower.

We now know a lot more about the polarization spiral and who is driving it.

More here.

Wednesday, August 17, 2022

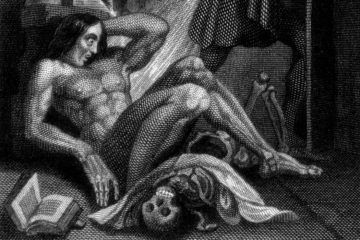

The Hoax That Inspired Mary Shelley

Emily Zarevich in JSTOR Daily:

Why do people keep falling for hoaxes? Moreover, what is it about certain hoaxes that maintain an iron hold on public imagination, long after their con is exposed? The Roger Dodsworth hoax of 1826 managed to fool so many people and remain in so many memories that a short story about it, published nearly forty years later, still seemed relevant to readers, writes English literature scholar Charles E. Robinson.

Why do people keep falling for hoaxes? Moreover, what is it about certain hoaxes that maintain an iron hold on public imagination, long after their con is exposed? The Roger Dodsworth hoax of 1826 managed to fool so many people and remain in so many memories that a short story about it, published nearly forty years later, still seemed relevant to readers, writes English literature scholar Charles E. Robinson.

Great Britain suffered through an usually hot summer in 1826, and the popular press took full advantage of it, banking on the unusual and “chilling” tale of the so-called Roger Dodsworth to sell copies. According to newspapers in Lyons, Rouen, and Paris, Dodsworth was the thirty-year-old son of the sixteenth-century English antiquarian Roger Dodsworth. As the story went, Dodsworth the younger had been frozen in ice for 166 years, having been trapped under a avalanche while on expedition at Mount St. Gothard in the Alps in 1660. The story was picked up in London; the most popular publications of the day sensationalized an already sensational tale. Even the conservative weekly John Bull published letters supposedly penned by the remarkable survivor. The public, fully under sway of the imagination and emotion that shaped the age of Romanticism, was enthralled and seduced by the story as it passed from page to page in the London papers.

More here.

A Biochemist’s View of Life’s Origin Reframes Cancer and Aging

Viviane Callier in Quanta:

All living cells power themselves by coaxing energetic electrons from one side of a membrane to the other. Membrane-based mechanisms for accomplishing this are, in a sense, as universal a feature of life as the genetic code. But unlike the genetic code, these mechanisms are not the same everywhere: The two simplest categories of cells, bacteria and archaea, have membranes and protein complexes for producing energy that are chemically and structurally dissimilar. Those differences make it hard to guess how the very first cells met their energy needs.

All living cells power themselves by coaxing energetic electrons from one side of a membrane to the other. Membrane-based mechanisms for accomplishing this are, in a sense, as universal a feature of life as the genetic code. But unlike the genetic code, these mechanisms are not the same everywhere: The two simplest categories of cells, bacteria and archaea, have membranes and protein complexes for producing energy that are chemically and structurally dissimilar. Those differences make it hard to guess how the very first cells met their energy needs.

This mystery led Nick Lane, a professor of evolutionary biochemistry at University College London, to an unorthodox hypothesis about the origin of life. What if life arose in a geological environment where electrochemical gradients across tiny barriers occurred naturally, supporting a primitive form of metabolism while cells as we know them evolved?

More here.

The Man Who Killed Millions and Saved Billions: Fritz Haber

The World Is Seeing How the Dollar Really Works

Adam Tooze in Foreign Policy:

2022 has been a year of dollar power—power that manifests itself in both overt and subtler forms.

2022 has been a year of dollar power—power that manifests itself in both overt and subtler forms.

In the spring, the financial sanctions slapped on Russia’s Central Bank following Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrated the extent of U.S. financial sway, especially when it is exerted in cooperation with America’s European partners. If you export far more than you import and thus hold really large foreign exchange reserves—like Russia’s $500 billion—there really is nowhere else to hold them other than dollars or euros. If it comes to a confrontation, that puts you at the mercy of the financial authorities of the United States and its alliance partners. NATO reveals itself to be a financial power.

Russia has, so far, ridden out the storm, but to do so it has had to close its financial system to the outside world. Its imports have been squeezed to barely more than half their pre-crisis level.

When the sanctions were applied, the shock to Russia provoked the question of whether a monetary system that conferred such one-sided power on the United States could possibly be sustainable.

More here.

Justice as a Larger Loyalty – Richard Rorty (1996)

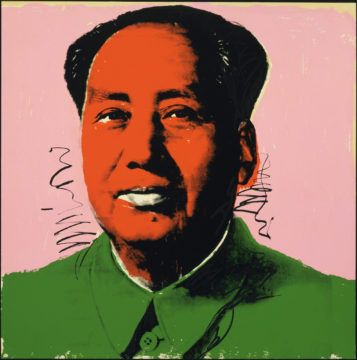

Warhol’s Mao Turns Fifty

Billy Anania at Art In America:

In 1982, a fifty-four-year-old Andy Warhol visited China for the first and only time in his life. Wandering the streets of Beijing ten years after producing his iconic portfolio of Mao Zedong portraits, he quickly took a liking to the uniformity of Chinese culture. “I like to wear the same thing every day,” he mused to Interview magazine photographer Christopher Makos, who reported this and other gnomic responses in the 2008 photobook Andy Warhol in China. Observing crowds of women and men all dressed in blue, Warhol remarked: “If I were a dress designer, I’d design one dress over and over.”

In 1982, a fifty-four-year-old Andy Warhol visited China for the first and only time in his life. Wandering the streets of Beijing ten years after producing his iconic portfolio of Mao Zedong portraits, he quickly took a liking to the uniformity of Chinese culture. “I like to wear the same thing every day,” he mused to Interview magazine photographer Christopher Makos, who reported this and other gnomic responses in the 2008 photobook Andy Warhol in China. Observing crowds of women and men all dressed in blue, Warhol remarked: “If I were a dress designer, I’d design one dress over and over.”

Warhol’s process in creating these prints mirrored that of the official Chinese artists who have painted fresh, identical portraits of Mao annually since 1950. Displayed prominently above the Gate of Heavenly Peace in Tiananmen Square, the 20-by-15-foot likeness of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) chairman, based on an easel-painting original by Zhang Zhenshi, reflects the cultural split of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from its imperial past.

more here.

Saint Augustine’s Slave Play

Daniel José Camacho at The Point:

I learned about Augustine of Hippo from my mother. She had memorized lines from his Confessions as a Catholic schoolgirl in the Caribbean village of Manatí in Colombia. “Our hearts are restless until they rest in God,” she would tell me. Even after she immigrated to the United States and became a born-again Protestant, she kept reciting him. When I left my home on Long Island to study philosophy at a liberal arts college out of state, her prayers followed me just as Monica’s trailed her son, Augustine, when he boarded a ship heading for Italy. I joked that she was my Monica. But I gradually developed my own relationship to Augustine. As I encountered him in a predominantly white academic setting, I latched on to him. He became more than the metaphysical or doctrinal positions parsed in class. Augustine was the symbol of a more diverse and global Christianity that had been covered up by white-supremacist lies. “The greatest thinkers of the early Church came from Africa!” I declared to amused peers. My Augustine was Black.

I learned about Augustine of Hippo from my mother. She had memorized lines from his Confessions as a Catholic schoolgirl in the Caribbean village of Manatí in Colombia. “Our hearts are restless until they rest in God,” she would tell me. Even after she immigrated to the United States and became a born-again Protestant, she kept reciting him. When I left my home on Long Island to study philosophy at a liberal arts college out of state, her prayers followed me just as Monica’s trailed her son, Augustine, when he boarded a ship heading for Italy. I joked that she was my Monica. But I gradually developed my own relationship to Augustine. As I encountered him in a predominantly white academic setting, I latched on to him. He became more than the metaphysical or doctrinal positions parsed in class. Augustine was the symbol of a more diverse and global Christianity that had been covered up by white-supremacist lies. “The greatest thinkers of the early Church came from Africa!” I declared to amused peers. My Augustine was Black.

more here.

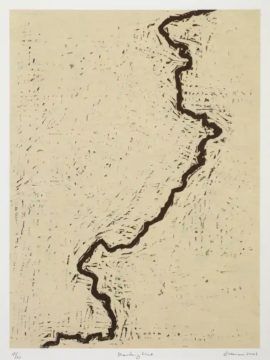

Where the Nile began: The perilous journey to seek the river’s source

David Conrads in The Christian Science Monitor:

It was a geographical mystery that had befuddled explorers, astronomers, and philosophers for two millennia: Where did the Nile begin? In “River of the Gods: Genius, Courage, and Betrayal in the Search for the Source of the Nile,” historian Candice Millard recounts the adventures of two ambitious, Victorian-era rivals who spent years trekking through East Africa, enduring unimaginable hardships, in an effort to be the first to solve the puzzle.

It was a geographical mystery that had befuddled explorers, astronomers, and philosophers for two millennia: Where did the Nile begin? In “River of the Gods: Genius, Courage, and Betrayal in the Search for the Source of the Nile,” historian Candice Millard recounts the adventures of two ambitious, Victorian-era rivals who spent years trekking through East Africa, enduring unimaginable hardships, in an effort to be the first to solve the puzzle.

European fascination with Egypt and the Middle East was sparked by the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799 and its deciphering 23 years later. While 19th-century explorers were scattered across the globe, filling in the map of the world, none had been able to locate the headwaters of the White Nile, the longest branch of the longest river in the world. The question of where the Nile began constituted, in Millard’s words, “the Holy Grail of exploration.”

Eager to seize the grail was Richard Francis Burton, a British explorer, scholar, linguist, and adventurer. Fluent in Arabic, as well as 24 other languages and 12 dialects, he disguised himself as a Muslim pilgrim and became the first Englishman to travel to Mecca, which was forbidden to non-Muslims, in 1853. The next year the newly formed Royal Geographical Society in London chose him to locate the headwaters of the Nile.

More here.

A New Theory in Physics Claims to Solve the Mystery of Consciousness

From Neuroscience News:

The ability of the brain to create consciousness has baffled some for millennia. The mystery of consciousness lies in the fact that each of us has subjectivity, something that is like to sense, feel and think. In contrast to being under anesthesia or in a dreamless deep sleep, while we’re awake we don’t “live in the dark” — we experience the world and ourselves. But how the brain creates the conscious experience and what area of the brain is responsible for this remains a mystery. According to Dr. Nir Lahav, a physicist from Bar-Ilan University in Israel, “This is quite a mystery since it seems that our conscious experience cannot arise from the brain, and in fact, cannot arise from any physical process.”

The ability of the brain to create consciousness has baffled some for millennia. The mystery of consciousness lies in the fact that each of us has subjectivity, something that is like to sense, feel and think. In contrast to being under anesthesia or in a dreamless deep sleep, while we’re awake we don’t “live in the dark” — we experience the world and ourselves. But how the brain creates the conscious experience and what area of the brain is responsible for this remains a mystery. According to Dr. Nir Lahav, a physicist from Bar-Ilan University in Israel, “This is quite a mystery since it seems that our conscious experience cannot arise from the brain, and in fact, cannot arise from any physical process.”

As strange as it sounds, the conscious experience in our brain, cannot be found or reduced to some neural activity.

“Think about it this way,” says Dr. Zakaria Neemeh, a philosopher from the University of Memphis, “when I feel happiness, my brain will create a distinctive pattern of complex neural activity. This neural pattern will perfectly correlate with my conscious feeling of happiness, but it is not my actual feeling. It is just a neural pattern that represents my happiness. That’s why a scientist looking at my brain and seeing this pattern should ask me what I feel, because the pattern is not the feeling itself, just a representation of it.”

More here.

Wednesday Poem

Shrinking Bear

Watching a bear shrink is an amazing thing. First, the bear raises a family. She works very hard. Her children love her very much. They love her so much, they have children of their own, and these grandchildren love her too, in different ways. This spectrum of love is the second step.

Third, the bear spends many hours and many days looking at the shadows of trees. She wishes she could climb them. Her paws tingle with the memory of getting oneself higher than the ground. The ground is so close to her now. She dreams in dirt.

Her many children come in & kiss her head, tell her how beautifully her hair shines. This happens for so long, the bear begins to think she is a person. This is the fourth step. It is the longest.

The final step cannot be measured. One day, the bear is festooned in smoke. Everyone covers their mouths & swipes their paws, trying to find her. When the smoke clears, the bear will be gone. Her children will spend the rest of their lives trying to pinpoint the moment the bear shrank, to no avail. It really is an amazing thing.

by Dalton Day

from Jellyfish Magazine

Tuesday, August 16, 2022

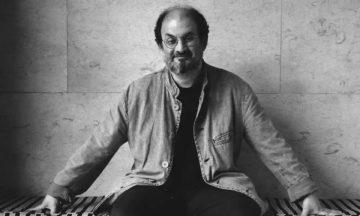

Where Salman Rushdie defied those who would silence him, today too many fear causing offence

Kenan Malik in The Guardian:

The Satanic Verses, Rushdie’s fourth novel, was as much an exploration of the migrant experience as it was about Islam, as savage in its indictment of racism as of religion. What mattered, though, was less what Rushdie wrote than what the novel came to symbolise. The 1980s was a decade that saw the beginnings of the breakdown of traditional political and moral boundaries, an unravelling with which we are still coming to terms.

The Satanic Verses, Rushdie’s fourth novel, was as much an exploration of the migrant experience as it was about Islam, as savage in its indictment of racism as of religion. What mattered, though, was less what Rushdie wrote than what the novel came to symbolise. The 1980s was a decade that saw the beginnings of the breakdown of traditional political and moral boundaries, an unravelling with which we are still coming to terms.

Rushdie was charting this new terrain, capturing the sense of displacement and dislocation, which he found exhilarating. The Satanic Verses was, he wrote while in hiding, “a love-song to our mongrel selves”, a work that “celebrates hybridity, impurity, intermingling, the transformation that comes of new and unexpected combinations of human beings, cultures, ideas, politics, movies, songs”. Many critics of The Satanic Verses believed “that intermingling with a different culture will inevitably weaken and ruin their own. I am of the opposite opinion.”

More here.

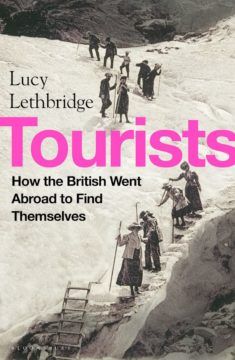

A History Of Tourism

Gillian Tindall at Literary Review:

Let us retreat again quickly into the more distant past. So much varied research has contributed to this excellent book that it is a treasure-trove of many more significant facts than one can cite. There are long excursions into the growth of the spa and into the wildly varying and often scientifically groundless advice on water, air (good and bad), exercise (ditto), diets, purges, rest (too much or too little) and underwear, elevated by Gustav Jaeger into something of a belief system. There is the rebranding of mountains from places full of only semi-enjoyable danger and dread into over-visited international playgrounds. Similarly, the sea moved through the centuries from being an object of respect and fear (Joseph Addison wrote in 1812 of the ‘pleasing Astonishment’ of seeing the ‘Heavings of this prodigious Bulk of Waters’) to one of enthusiasm, a focus of the cult of bathing. And there is the more recent shift in concepts of beauty, from the Rossetti pallor of the True Woman to the class-free obsession with sunburn, which came with the tourism boom of the 1950s and 1960s instigated by cheap airfares.

Let us retreat again quickly into the more distant past. So much varied research has contributed to this excellent book that it is a treasure-trove of many more significant facts than one can cite. There are long excursions into the growth of the spa and into the wildly varying and often scientifically groundless advice on water, air (good and bad), exercise (ditto), diets, purges, rest (too much or too little) and underwear, elevated by Gustav Jaeger into something of a belief system. There is the rebranding of mountains from places full of only semi-enjoyable danger and dread into over-visited international playgrounds. Similarly, the sea moved through the centuries from being an object of respect and fear (Joseph Addison wrote in 1812 of the ‘pleasing Astonishment’ of seeing the ‘Heavings of this prodigious Bulk of Waters’) to one of enthusiasm, a focus of the cult of bathing. And there is the more recent shift in concepts of beauty, from the Rossetti pallor of the True Woman to the class-free obsession with sunburn, which came with the tourism boom of the 1950s and 1960s instigated by cheap airfares.

more here.

The Work of Mark Fisher w/ Matt Colquhoun

A Conversation with Anuradha Roy

Pankaj Mishra at Paris Review:

I met the novelist Anuradha Roy in Delhi in the mid-nineties, when she was an editor at Oxford University Press and I had just published my first book. Not long after that, she moved to a Himalayan town to set up Permanent Black, now India’s premier intellectual publisher, with her husband, Rukun Advani. She also began to write fiction. Her fifth novel, The Earthspinner, which was released in the United States this summer, is about the war on reason and on imagination in a world consumed by political fanaticism.

I met the novelist Anuradha Roy in Delhi in the mid-nineties, when she was an editor at Oxford University Press and I had just published my first book. Not long after that, she moved to a Himalayan town to set up Permanent Black, now India’s premier intellectual publisher, with her husband, Rukun Advani. She also began to write fiction. Her fifth novel, The Earthspinner, which was released in the United States this summer, is about the war on reason and on imagination in a world consumed by political fanaticism.

Though I don’t remember what was said in our first meeting, I can recall a certain hopefulness in the air—there was a lot of that about, among publishers and writers, in India in the nineties. Writing in English was ceasing to be the furtive and poorly paid endeavor it long had been. There were greater opportunities to publish; new literary periodicals and networks of promotion seemed to be creating the infrastructure for more vigorous intellectual and artistic life. Indeed, the conventional wisdom of that decade, helped by the prominence of Salman Rushdie, Vikram Seth, and Arundhati Roy abroad, was that Indian writing in English was “arriving,” no less resoundingly than was India’s embrace of consumer capitalism at the end of history.

more here.

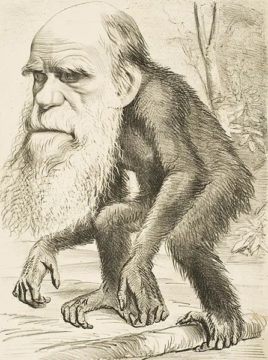

What we talk about when we compare chimps to humans genetically

Razib Khan in Unsupervised Learning:

Peter Singer has been making the case for extending human rights to chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans for over three decades. Singer outlined his argument in 1993’s The Great Ape Project: Equality Beyond Humanity. The reaction was generally positive, with Carl Sagan pointing out that we “share over 99% of our active genes with chimpanzees and gorillas…It challenges us to reassess many of our ethical assumptions.”

Peter Singer has been making the case for extending human rights to chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans for over three decades. Singer outlined his argument in 1993’s The Great Ape Project: Equality Beyond Humanity. The reaction was generally positive, with Carl Sagan pointing out that we “share over 99% of our active genes with chimpanzees and gorillas…It challenges us to reassess many of our ethical assumptions.”

You’ve probably come across Sagan’s statistic before, usually stated in a form like: humans share 98 to 99 percent of our genes with chimpanzees. But where does this oft-repeated number come from? And how could Sagan confidently assert it when writing his review seven years before the first draft of the human genome was even completed in 2000? Is it even accurate?

More here.

Pankaj Mishra and Ali Sethi: On the anniversary of partition, let’s consign the pitiless logic of Hindu v Muslim to the past

Pankaj Mishra and Ali Sethi in The Guardian:

In a remarkable document from the 13th century, a Sufi writer records his epiphany about the prophet Muhammad granting permission to music in India. Quoting an enigmatic utterance of the prophet (“I sense the breath of the Merciful coming from Yemen”), he speculates that the “Yemen” in question is not just the region in the Arabian peninsula, but possibly also the popular Indian raga of the same name. These days, such an innocuous interpretation, linking the founder of Islam to northern Indian music, is certain to incite charges of blasphemy, and perhaps even calls for assassination, across many Muslim populations.

In a remarkable document from the 13th century, a Sufi writer records his epiphany about the prophet Muhammad granting permission to music in India. Quoting an enigmatic utterance of the prophet (“I sense the breath of the Merciful coming from Yemen”), he speculates that the “Yemen” in question is not just the region in the Arabian peninsula, but possibly also the popular Indian raga of the same name. These days, such an innocuous interpretation, linking the founder of Islam to northern Indian music, is certain to incite charges of blasphemy, and perhaps even calls for assassination, across many Muslim populations.

But it would have been uncontroversial, even unremarkable, during much of the last millennium, the centuries during which India was the world’s busiest crossroads, receiving and transmitting cultural influences between east and west, north and south. Artists and thinkers in this time, when India played easy-going host to a polyphony of identities, were oblivious to today’s hotly invoked distinctions of religion and gender.

More here.

The most significant genius: Emmy Noether

why modern medicine can’t work without stories

Polly Morland in The Guardian:

Most of us over the age of 30 can remember the family doctor we had when we were kids. They met us as babies and watched us grow up. They knew our stories, those of our siblings, our parents and often our grandparents, too. These stories were fundamental to the bond of trust between doctors and their patients. We are now learning that this deep, accumulated knowledge was also palpably beneficial in medical terms.

Most of us over the age of 30 can remember the family doctor we had when we were kids. They met us as babies and watched us grow up. They knew our stories, those of our siblings, our parents and often our grandparents, too. These stories were fundamental to the bond of trust between doctors and their patients. We are now learning that this deep, accumulated knowledge was also palpably beneficial in medical terms.

The stories came in fragments, of course. Any GP will tell you this: that alongside the medical history, there are glimpses of the life that accompanies it: a past trauma, a triumph, a family crisis, a morbid fear or a reason to hope. Reducing any patient to their affliction, the tumorous breast or lazy pancreas, is akin to regarding a book as nothing more than paper and ink. This focus on the whole person, while valuable in all medical disciplines, is bread-and-butter work for GPs. Their role as the keeper of patients’ stories is what most of them love about their job, or what they used to.

More here.