Daniel Spaulding at Art In America:

In criticism as in war, the law of proportionate response enjoys only occasional observance. Gerhard Richter: Painting after the Subject of History is the fruit of what its author, art historian Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, calls the “nearly unfathomable duration” of his engagement with the most influential German painter since World War II. “Unfathomable” is an overstatement, but only just. Buchloh has been thinking about Richter for half a century. The result is a book that comes in at just over 650 pages divvied up between no fewer than 20 chapters, most of which began as independent essays published between the 1980s and the present.

In criticism as in war, the law of proportionate response enjoys only occasional observance. Gerhard Richter: Painting after the Subject of History is the fruit of what its author, art historian Benjamin H.D. Buchloh, calls the “nearly unfathomable duration” of his engagement with the most influential German painter since World War II. “Unfathomable” is an overstatement, but only just. Buchloh has been thinking about Richter for half a century. The result is a book that comes in at just over 650 pages divvied up between no fewer than 20 chapters, most of which began as independent essays published between the 1980s and the present.

Curiously, given that Richter is by all evidence Buchloh’s favorite artist (or at any rate, the one who sustains the biggest share of his attention), their relationship has been marked from the beginning by profound differences of approach.

more here.

If Guston was labeled an Abstract Expressionist for his nonobjective takes on Monet, Walker could fairly be described as an Abstract Romanticist for his nonobjective takes on John Constable, to whose paintings Walker was introduced as a child in Birmingham, England. In the catalogue, French describes his training at the Birmingham School of Art in the late 1950s as “rigorously traditional” and tells of the artist’s profound confusion upon discovering a Malevich canvas that impressed him by capturing all the emotion that he had experienced regarding Rembrandt’s Jewish Bride. Early on he realized that technique did not amount to feeling.

If Guston was labeled an Abstract Expressionist for his nonobjective takes on Monet, Walker could fairly be described as an Abstract Romanticist for his nonobjective takes on John Constable, to whose paintings Walker was introduced as a child in Birmingham, England. In the catalogue, French describes his training at the Birmingham School of Art in the late 1950s as “rigorously traditional” and tells of the artist’s profound confusion upon discovering a Malevich canvas that impressed him by capturing all the emotion that he had experienced regarding Rembrandt’s Jewish Bride. Early on he realized that technique did not amount to feeling. T

T Matthew Weiss dreams of the day when his oncology practice will operate very differently. A surgeon at the Northwell Health System in New York who treats pancreatic cancer—one of the deadliest malignancies known—he doesn’t have a lot of choices when it comes to saving his patients. Some people with pancreatic tumors die within a few weeks and others fight longer, but only

Matthew Weiss dreams of the day when his oncology practice will operate very differently. A surgeon at the Northwell Health System in New York who treats pancreatic cancer—one of the deadliest malignancies known—he doesn’t have a lot of choices when it comes to saving his patients. Some people with pancreatic tumors die within a few weeks and others fight longer, but only  Initial detractors called Minimalism “cold” and “inhuman,” and subsequent opponents deemed it “masculinist” and “totalitarian.” I still see these responses as emotionally reactive or formally reductive or both, and, like several other critics, I have stressed the phenomenological dimension of Minimalism, its engagement with the body and the space of the viewer, in part to counter such readings. Nonetheless, they did represent the sentiments of many observers, and some of these accounts also point to the historical problem at issue here, even if, to my mind, they misconstrue it in doing so.11 For what was taken as “inhuman” in Minimalist practice is better understood as “antihumanist,” a position that was largely shared by Conceptual artists. This antihumanism was active, for example, when, in another well-known conversation from 1966, Frank Stella and Donald Judd claimed to jettison European “rationalism,” and when Bochner insisted a year later that Conceptualists sought to bracket all considerations of style and metaphor.12 Not only a local reaction against late Abstract Expressionism, this rejection, widespread among artists, writers, and philosophers of the time, targeted a humanism that had had no effective answer for fascism, the Holocaust, or the Bomb and that continued to fail in the face of American imperialism in Southeast Asia and elsewhere.

Initial detractors called Minimalism “cold” and “inhuman,” and subsequent opponents deemed it “masculinist” and “totalitarian.” I still see these responses as emotionally reactive or formally reductive or both, and, like several other critics, I have stressed the phenomenological dimension of Minimalism, its engagement with the body and the space of the viewer, in part to counter such readings. Nonetheless, they did represent the sentiments of many observers, and some of these accounts also point to the historical problem at issue here, even if, to my mind, they misconstrue it in doing so.11 For what was taken as “inhuman” in Minimalist practice is better understood as “antihumanist,” a position that was largely shared by Conceptual artists. This antihumanism was active, for example, when, in another well-known conversation from 1966, Frank Stella and Donald Judd claimed to jettison European “rationalism,” and when Bochner insisted a year later that Conceptualists sought to bracket all considerations of style and metaphor.12 Not only a local reaction against late Abstract Expressionism, this rejection, widespread among artists, writers, and philosophers of the time, targeted a humanism that had had no effective answer for fascism, the Holocaust, or the Bomb and that continued to fail in the face of American imperialism in Southeast Asia and elsewhere. On my first viewing of Top Gun: Maverick, I was moved to tears. Many men who I’ve spoken to about the film have admitted to crying while they watched it. I cried, despite my awareness that I was being aggressively manipulated by a work of vainglorious, sentimental, and stupid propaganda for the US military. This is the only Cruise film which has moved me in this way. Between the aerial stunts, Top Gun: Maverick is a film about coming to terms with the death of the father: Cruise’s Maverick finds himself stuck in the complex situation of grieving for his peer, Iceman (Val Kilmer), who had become his surrogate father-protector, while simultaneously navigating his own role as a surrogate father-protector to Rooster (Miles Teller), the son of the man whose death he caused in the film’s prequel. Kilmer is only two years older than Cruise, but in Top Gun: Maverick he is coded as older and wiser, almost a mentor, due to his seniority in rank. Cruise/Maverick’s peers have aged around him, but he remains stuck in perpetual adolescence. This is a recent example of a long trend: Cruise’s filmography is filled with troubled relationships between absent or disappointing fathers and the sons who suffer. There is certainly scope for speculation about the influence the difficult relationship with his own father has had on the roles Cruise chooses and shapes.

On my first viewing of Top Gun: Maverick, I was moved to tears. Many men who I’ve spoken to about the film have admitted to crying while they watched it. I cried, despite my awareness that I was being aggressively manipulated by a work of vainglorious, sentimental, and stupid propaganda for the US military. This is the only Cruise film which has moved me in this way. Between the aerial stunts, Top Gun: Maverick is a film about coming to terms with the death of the father: Cruise’s Maverick finds himself stuck in the complex situation of grieving for his peer, Iceman (Val Kilmer), who had become his surrogate father-protector, while simultaneously navigating his own role as a surrogate father-protector to Rooster (Miles Teller), the son of the man whose death he caused in the film’s prequel. Kilmer is only two years older than Cruise, but in Top Gun: Maverick he is coded as older and wiser, almost a mentor, due to his seniority in rank. Cruise/Maverick’s peers have aged around him, but he remains stuck in perpetual adolescence. This is a recent example of a long trend: Cruise’s filmography is filled with troubled relationships between absent or disappointing fathers and the sons who suffer. There is certainly scope for speculation about the influence the difficult relationship with his own father has had on the roles Cruise chooses and shapes. This is a meticulous and deliberate and beautiful book.

This is a meticulous and deliberate and beautiful book. According to professor emeritus Andrew Hacker of Queens College of the City University of New York, less than five percent of Americans will ever use any higher math at all in their jobs, including not only calculus but algebra, geometry, and trigonometry. And less than one percent will ever use calculus on the job. Born in 1929 and holding a PhD from Princeton, Hacker taught college political science for decades and has also been a math professor. His book

According to professor emeritus Andrew Hacker of Queens College of the City University of New York, less than five percent of Americans will ever use any higher math at all in their jobs, including not only calculus but algebra, geometry, and trigonometry. And less than one percent will ever use calculus on the job. Born in 1929 and holding a PhD from Princeton, Hacker taught college political science for decades and has also been a math professor. His book  The brutal

The brutal  It was June, 1981. Elizabeth Hardwick was in Castine, the small town in Maine where she’d spent her summers for more than twenty years, since before her daughter, Harriet, was born. Even after Robert Lowell, her husband, left her, in 1970, she kept going. The flight from New York City to Bangor took only an hour; the rental car to Castine added another. “The drive is very nostalgia-creating,” she told me. When she arrived, she’d go grocery shopping, check in on the local couple who looked after the house for her, and be settled in by the time her old friend Mary McCarthy phoned. Mary and her husband had been coming to Castine almost as long as Elizabeth had. Mary lived on Main Street, but Elizabeth had remodelled a house on a bluff overlooking the water.

It was June, 1981. Elizabeth Hardwick was in Castine, the small town in Maine where she’d spent her summers for more than twenty years, since before her daughter, Harriet, was born. Even after Robert Lowell, her husband, left her, in 1970, she kept going. The flight from New York City to Bangor took only an hour; the rental car to Castine added another. “The drive is very nostalgia-creating,” she told me. When she arrived, she’d go grocery shopping, check in on the local couple who looked after the house for her, and be settled in by the time her old friend Mary McCarthy phoned. Mary and her husband had been coming to Castine almost as long as Elizabeth had. Mary lived on Main Street, but Elizabeth had remodelled a house on a bluff overlooking the water. Imagine you have 20 new compounds that have shown some effectiveness in treating a disease like tuberculosis (TB), which affects 10 million people worldwide and kills 1.5 million each year. For effective treatment, patients will need to take a combination of three or four drugs for months or even years because the TB bacteria behave differently in different environments in cells—and in some cases evolve to become drug-resistant. Twenty compounds in three- and four-drug combinations offer nearly 6,000 possible combinations. How do you decide which drugs to test together?

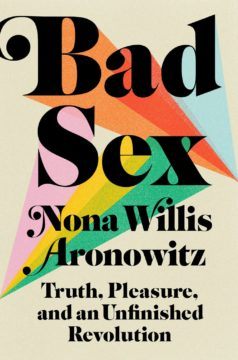

Imagine you have 20 new compounds that have shown some effectiveness in treating a disease like tuberculosis (TB), which affects 10 million people worldwide and kills 1.5 million each year. For effective treatment, patients will need to take a combination of three or four drugs for months or even years because the TB bacteria behave differently in different environments in cells—and in some cases evolve to become drug-resistant. Twenty compounds in three- and four-drug combinations offer nearly 6,000 possible combinations. How do you decide which drugs to test together? For Ellen Willis, feminism represented the possibility of being defiantly, boldly herself. Willis wasn’t so concerned with fitting into a single political camp; she loved, for example, rock and roll, even songs that had outrageously misogynistic lyrics. “Music that boldly and aggressively laid out what the singer wanted, loved, hated,” she wrote in an essay about bands such as the Sex Pistols and Ramones, “challenged me to do the same.” Meanwhile, she was bored by the “wimpiness” of milder, mellower, bands, including those that were explicitly feminist. Feminism allowed her to sort through these messy and incongruous pleasures freed from shame; to relish when her unruly feelings revealed a peculiar, unique kernel of self.

For Ellen Willis, feminism represented the possibility of being defiantly, boldly herself. Willis wasn’t so concerned with fitting into a single political camp; she loved, for example, rock and roll, even songs that had outrageously misogynistic lyrics. “Music that boldly and aggressively laid out what the singer wanted, loved, hated,” she wrote in an essay about bands such as the Sex Pistols and Ramones, “challenged me to do the same.” Meanwhile, she was bored by the “wimpiness” of milder, mellower, bands, including those that were explicitly feminist. Feminism allowed her to sort through these messy and incongruous pleasures freed from shame; to relish when her unruly feelings revealed a peculiar, unique kernel of self. Wilderson and Hartman insist that Afropessimism is not a politics (ARA 42–43, 56–57; SOS 65), but that demurral is either naïve or disingenuous. Counsel against pursuit of solidarities with nonblacks is a political stance and a potentially quite consequential one at that. And Afropessimism’s groupist focus proceeds from a class politics that represents the perspectives and concerns of a narrow stratum as those of the entire racialized population. Wilderson displays this class perspective in his romanticization of “Black suffering” (AP 328–331f).

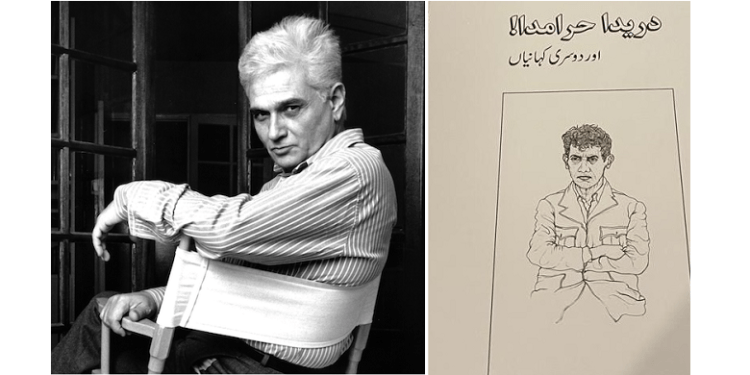

Wilderson and Hartman insist that Afropessimism is not a politics (ARA 42–43, 56–57; SOS 65), but that demurral is either naïve or disingenuous. Counsel against pursuit of solidarities with nonblacks is a political stance and a potentially quite consequential one at that. And Afropessimism’s groupist focus proceeds from a class politics that represents the perspectives and concerns of a narrow stratum as those of the entire racialized population. Wilderson displays this class perspective in his romanticization of “Black suffering” (AP 328–331f). The title story of Julien’s short story collection Derrida Haramda! introduces us to Shahid Wirk (or, as he is lovingly called by his friends, Sheeda) from Sheikhupura, who writes a surreal novel “Nazia” inspired by André Breton’s iconic surrealist work Nadja. Shahid’s novel is as an absurd piece of writing about a strange woman who haunts the streets of Sheikhupura. The narrator follows the woman at night, walking the city’s empty streets, and as he walks and walks, he is slowly confronted by the alienation he feels in the city, whose streets have emptied as if the city had been wiped clean of humans and animals by a poisonous gas. Julien’s stories often engage these peculiar and, at times, monstrous relationships and affiliations between European and South Asian creative work.

The title story of Julien’s short story collection Derrida Haramda! introduces us to Shahid Wirk (or, as he is lovingly called by his friends, Sheeda) from Sheikhupura, who writes a surreal novel “Nazia” inspired by André Breton’s iconic surrealist work Nadja. Shahid’s novel is as an absurd piece of writing about a strange woman who haunts the streets of Sheikhupura. The narrator follows the woman at night, walking the city’s empty streets, and as he walks and walks, he is slowly confronted by the alienation he feels in the city, whose streets have emptied as if the city had been wiped clean of humans and animals by a poisonous gas. Julien’s stories often engage these peculiar and, at times, monstrous relationships and affiliations between European and South Asian creative work.