Tara Parker-Pope in The Washington Post:

Category: Recommended Reading

Why the Brain Loves Music, Dr. Oliver Sacks

Friday Poem

Talk

The body is never silent. Aristotle said that we

can’t hear the music of the spheres because it is the

first thing that we hear, blood at the ear. Also the

body is brewing its fluids. It is braiding the rope of

food that moors us to the dead. Because it sniffles

and farts, we love the unpredictable. Because

breath goes in and out, there are two of each of us

and they distrust each other. The body’s reassuring

slurps and creaks are like a dial tone: we can

call up the universe. And so we are always

talking. My body and I sit up late, telling each other

our troubles. And when two bodies are near each

other, they begin talking in body-sonar. The art of

conversation is not dead! Still, for long periods, it is

comatose. For example, suppose my body doesn’t

get near enough to yours for a long time. It is dis-

consolate. Normally it talks to me all night: listening

is how I sleep. Now it is truculent. It wants to speak

directly to your body. The next voice to hear will

be my body’s. It sounds the same way blood sounds

at your ear. It is saying Ssshhh, now that we, at

last, are silent.

by William Matthews

from Sleek for the Long Flight

White Pine Press, 1988

Thursday, October 20, 2022

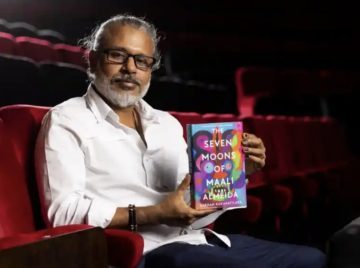

Shehan Karunatilaka wins Booker prize for The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida

Sarah Shaffi and Lucy Knight in The Guardian:

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Sri Lankan author Shehan Karunatilaka has won the Booker prize for fiction. The judges praised the “ambition of its scope, and the hilarious audacity of its narrative techniques”.

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Sri Lankan author Shehan Karunatilaka has won the Booker prize for fiction. The judges praised the “ambition of its scope, and the hilarious audacity of its narrative techniques”.

Karunatilaka’s second novel, The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida comes more than a decade after his debut, Chinaman, which was published in 2011. The Booker-winning novel tells the story of the photographer of its title, who in 1990 wakes up dead in what seems like a celestial visa office. With no idea who killed him, Maali has seven moons to contact the people he loves most and lead them to a hidden cache of photos of civil war atrocities that will rock Sri Lanka.

Neil MacGregor, chair of the judges for this year’s prize, said the novel was chosen because “it’s a book that takes the reader on a rollercoaster journey through life and death right to what the author describes as the dark heart of the world”.

More here.

Self-Taught AI Shows Similarities to How the Brain Works

Anil Ananthaswamy in Quanta:

Now some computational neuroscientists have begun to explore neural networks that have been trained with little or no human-labeled data. These “self-supervised learning” algorithms have proved enormously successful at modeling human language and, more recently, image recognition. In recent work, computational models of the mammalian visual and auditory systems built using self-supervised learning models have shown a closer correspondence to brain function than their supervised-learning counterparts. To some neuroscientists, it seems as if the artificial networks are beginning to reveal some of the actual methods our brains use to learn.

Now some computational neuroscientists have begun to explore neural networks that have been trained with little or no human-labeled data. These “self-supervised learning” algorithms have proved enormously successful at modeling human language and, more recently, image recognition. In recent work, computational models of the mammalian visual and auditory systems built using self-supervised learning models have shown a closer correspondence to brain function than their supervised-learning counterparts. To some neuroscientists, it seems as if the artificial networks are beginning to reveal some of the actual methods our brains use to learn.

More here.

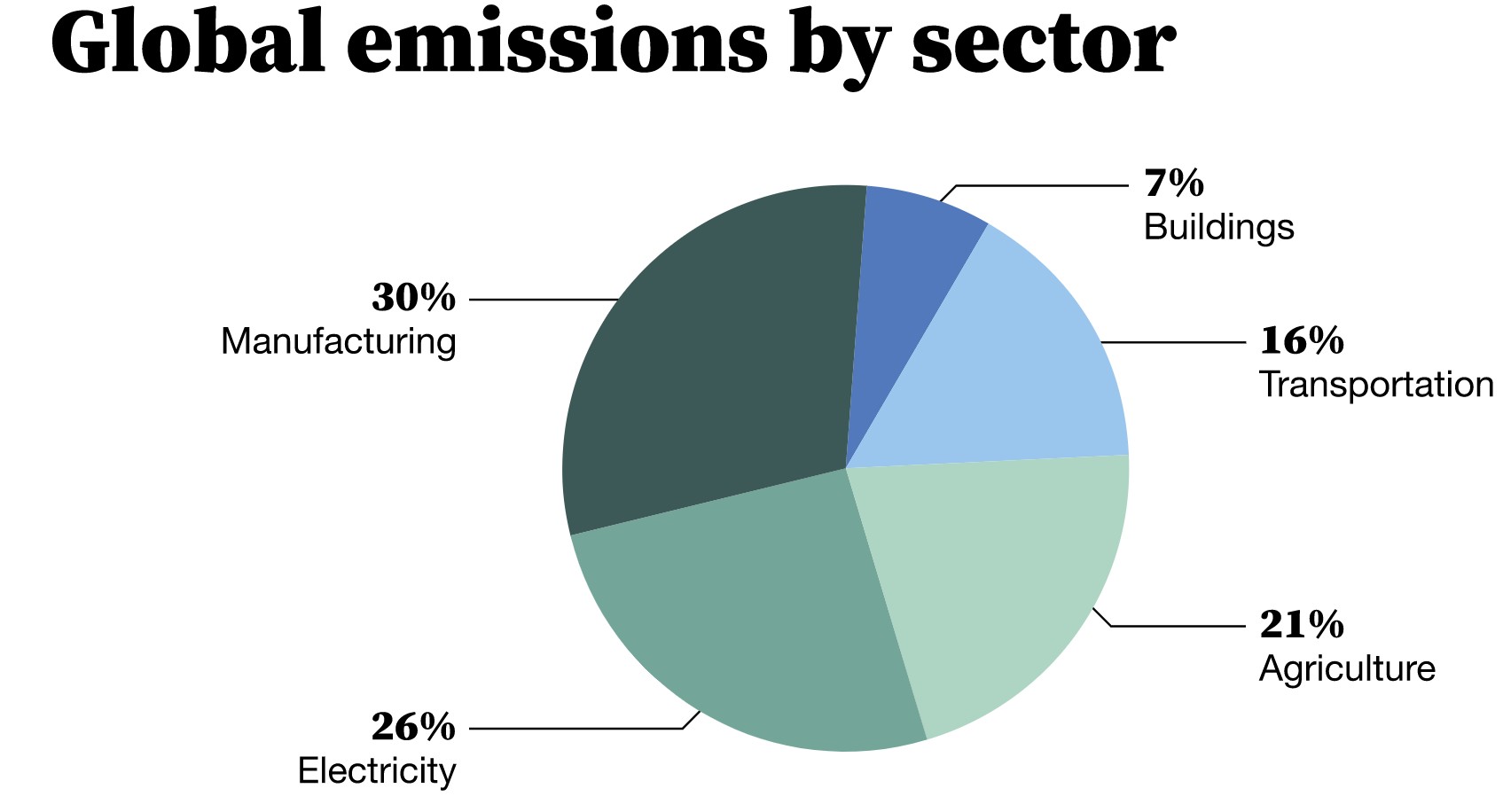

Bill Gates: How we’re doing on the path to zero emissions

Bill Gates’s annual memo about the journey to zero emissions

Bill Gates in his blog, Gates Notes:

When I first started learning about climate change 15 years ago, I came to three conclusions. First, avoiding a climate disaster would be the hardest challenge people had ever faced. Second, the only way to do it was to invest aggressively in clean-energy innovation and deployment. And third, we needed to get going.

When I first started learning about climate change 15 years ago, I came to three conclusions. First, avoiding a climate disaster would be the hardest challenge people had ever faced. Second, the only way to do it was to invest aggressively in clean-energy innovation and deployment. And third, we needed to get going.

Since then, an influx of private and public investment has accelerated innovation faster than I dared hope. This progress makes me optimistic about the future.

But I am also realistic about the present. The world still needs to reduce annual greenhouse gas emissions from 51 billion tons to zero, but global emissions continue to increase every year. If you follow the annual IPCC reports, you’ve watched as the scenarios for limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5 or even 2 degrees Celsius become increasingly remote. And some of the clean technologies we need are still very far from becoming practical, cost-effective solutions we can deploy at scale.

More here.

What The Rosetta Stone Actually Says

When the Push Button Was New, People Were Freaked

Matthew Wills at JSTOR Daily:

The doorbell. The intercom. The elevator. Once upon a time, beginning in the late nineteenth century, pushing the button that activated such devices was a strange new experience. The electric push button, the now mundane-seeming interface between human and machine, was originally a spark for wonder, anxiety, and social transformation.

As media studies scholar Rachel Plotnick details, people worried that the electric push button would make human skills atrophy. They wondered if such devices would seal off the wonders of technology into a black box: “effortless, opaque, and therefore unquestioned by consumers.” Today, you’d probably have to schedule an electrician to fix what some children back then knew how to make: electric bells, buttons, and buzzers.

more here.

The Meaning Of Classicism

Amit Chaudhuri at n+1:

OVER A DECADE AGO, I began to inadvertently call my mother’s singing “classicist.” I say “inadvertently” because I think I was, without fully realizing it, using the word in Eliot’s sense. My mother, Bijoya Chaudhuri, was a singer of Tagore songs—largely ignored, but admired by a few for being one of the great singers of her generation. In using “classicist,” I may have meant to connect her style to North Indian classical music. And North Indian classical music is “classicist” in the way Eliot, I believe, uses the word: vocal music in this tradition preoccupies itself with the expression of the note, of the raga, but not with emotion in the conventional humanist sense—that is, not with self-expression. One of the ways it does this is by eschewing vibrato and tremolo, which became such an effective means of bringing emotional drama to opera in the Romantic period. However intricate the embellishments in North Indian classical vocal music (and they are the most complex and difficult in any vocal tradition), they must return repeatedly to the stillness (thheherao) and purity of the note. One of the ways this happens is through the ah sound that dominates North Indian classical vocal music.

OVER A DECADE AGO, I began to inadvertently call my mother’s singing “classicist.” I say “inadvertently” because I think I was, without fully realizing it, using the word in Eliot’s sense. My mother, Bijoya Chaudhuri, was a singer of Tagore songs—largely ignored, but admired by a few for being one of the great singers of her generation. In using “classicist,” I may have meant to connect her style to North Indian classical music. And North Indian classical music is “classicist” in the way Eliot, I believe, uses the word: vocal music in this tradition preoccupies itself with the expression of the note, of the raga, but not with emotion in the conventional humanist sense—that is, not with self-expression. One of the ways it does this is by eschewing vibrato and tremolo, which became such an effective means of bringing emotional drama to opera in the Romantic period. However intricate the embellishments in North Indian classical vocal music (and they are the most complex and difficult in any vocal tradition), they must return repeatedly to the stillness (thheherao) and purity of the note. One of the ways this happens is through the ah sound that dominates North Indian classical vocal music.

more here.

Thursday Poem

The Such Thing As the Ridiculous Question –

Where are you from???

When I say ancestors, let’s be clear:

I mean slaves. I’m talkin’ Tennessee

cotton & Louisiana suga. I mean grave

dirt. I come from homes & marriages

named after the same type of weapon –

all it takes is a shotgun to know

I’m Black. I don’t got no secrets

a bullet ain’t told. Danger see me

& sit down somewhere.

I’m a direct descendant of last words

& first punches. I got stolen blood.

My complexion is America’s

darkest hour. You can trace my great

great great great great grandmother back

to a scream. I bet somewhere it’s a haint

with my eyes. My last name is a protest;

a brick through a window in a house

my bones built. One million

scabs from one scar.

Heavy is the hand that held

the whip. Black is the back that carried this

country & when this country’s palm gets

an itch, I become money. You give this country

an inch & it will take a freedom. You can’t talk slick

to this legacy of oiled scalps. You can’t spit

on my race & call it reign. I sound like my mama now,

who sound like her mama who sound like her mama who

sound like her mama, who sound like her

mama who sound like her mama who sound like her

mama who sound like her mama, who sound like a scream.

& that’s why I’m so loud, remember? You wanna know

where I’m from? Easy. Open a wound

& watch it heal.

by Siaara Freeman

from Split This Rock

Listen to reading: here

Perfectionists: Lowering your standards can improve your mental health

Tracy Dennis-Tiwary in The Washington Post:

The standards to which perfectionists hold themselves are unrealistic, overly demanding and often impossible to achieve. And when perfectionists fail to achieve perfection? We beat ourselves up with harsh self-criticism and are less able to bounce back and learn from mistakes. We’re also unlikely to celebrate our achievements or take pride in improving on our personal best. To a perfectionist, it’s all or nothing — you can be a winner or you can be an abject, worthless failure, with nothing in between.

More here.

Racism: Overcoming science’s toxic legacy

The Editorial Board at Nature:

Science is “a shared experience, subject both to the best of what creativity and imagination have to offer and to humankind’s worst excesses”. So wrote the guest editors of this special issue of Nature, Melissa Nobles, Chad Womack, Ambroise Wonkam and Elizabeth Wathuti, in a June 2022 editorial announcing their involvement. Among those worst excesses is racism. For centuries, science has built a legacy of excluding people of colour and those from other historically marginalized groups from the scientific enterprise. Institutions and scientists have used research to underpin discriminatory thinking, and have prioritized research outputs that ignore and further disadvantage marginalized people.

Science is “a shared experience, subject both to the best of what creativity and imagination have to offer and to humankind’s worst excesses”. So wrote the guest editors of this special issue of Nature, Melissa Nobles, Chad Womack, Ambroise Wonkam and Elizabeth Wathuti, in a June 2022 editorial announcing their involvement. Among those worst excesses is racism. For centuries, science has built a legacy of excluding people of colour and those from other historically marginalized groups from the scientific enterprise. Institutions and scientists have used research to underpin discriminatory thinking, and have prioritized research outputs that ignore and further disadvantage marginalized people.

In the minds of many who do not experience it day to day, racism consists of egregious acts of violence or abuse. But that is only part of what many people experience in science. It is also, in the words of Black geoscientist Martha Gilmore, a “persistent current in everyday interactions” — of belittlement, of denial of opportunity, of feeling that you do not belong.

More here.

Wednesday, October 19, 2022

Muddy Waters – Live In Chicago 1979

The Secret Life Of Leftovers

Nat Watkins at The New Atlantis:

I have worked in restaurants, lived on sustenance homesteads, volunteered for aquaponics and permaculture farms, and harvested at food forests from Hawaii to Texas. I invariably come home with a crate of spare cuttings and leftovers that no one else wants. My pockets are often full of uneaten complimentary bread.

I have worked in restaurants, lived on sustenance homesteads, volunteered for aquaponics and permaculture farms, and harvested at food forests from Hawaii to Texas. I invariably come home with a crate of spare cuttings and leftovers that no one else wants. My pockets are often full of uneaten complimentary bread.

This is possible because I live in a country where 30 to 40 percent of food produced is never eaten, where the average family throws out $1,500 worth of food every year, and where a typical restaurant discards about a half-pound of food per meal.

This is an astonishing historical anomaly. In almost any other time and place in human history, someone would look at the very same waste and say, “Looks delicious!”

more here.

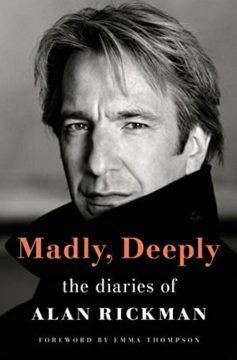

Madly, Deeply: The Alan Rickman Diaries

Thomas W Hodgkinson at Literary Review:

For anyone with a sneaker for the man and his work, these diaries are a delight. For one thing, they’re filled with his acerbic verdicts on the films and plays he sees. Vicky Cristina Barcelona he dismisses as ‘Woman’s Weekly tosh’, which seems about right. He’s no fan of the over-praised Last Seduction, noting that ‘an espresso is more rewarding’. As for Marvin’s Room, he complains it’s ‘another of those American plays which insist that you feel something’, before adding wryly, ‘I don’t think anger & frustration is what they had in mind.’

For anyone with a sneaker for the man and his work, these diaries are a delight. For one thing, they’re filled with his acerbic verdicts on the films and plays he sees. Vicky Cristina Barcelona he dismisses as ‘Woman’s Weekly tosh’, which seems about right. He’s no fan of the over-praised Last Seduction, noting that ‘an espresso is more rewarding’. As for Marvin’s Room, he complains it’s ‘another of those American plays which insist that you feel something’, before adding wryly, ‘I don’t think anger & frustration is what they had in mind.’

There are also two or three terrific anecdotes involving the glittering cast list of his friends and acquaintances. I loved Rupert Everett’s dry reply to Ruby Wax’s question about how his career is going: ‘Endlessly clawing my way back to the middle.’ Better still is Rickman’s own riposte when John Major approaches him in the stands at the 2011 Wimbledon men’s final. ‘You have given us so much enjoyment,’ gushes the former Tory prime minister. To which Rickman, a lifelong Labour supporter, cannot resist replying, ‘I wish I could say the same of you.’

more here.

Robert Pinsky on His Many Readings of Robert Lowell

Robert Pinsky in Literary Hub:

Life Studies is Robert Lowell’s best-known and most influential book. It won the National Book Award for poetry in 1960. I read it in 1962 and I hated it. In a shallow way, my dislike was a matter of social class. I said aloud to Lowell’s book, “Yeah, I had a grandfather, too.” Like my fellow would-be urban Beatniks at Rutgers, I preferred the manners of Allen Ginsberg’s “Kaddish”—the poet reading the Hebrew prayer for the dead while listening to Ray Charles and walking the streets of Greenwich Village.

Life Studies is Robert Lowell’s best-known and most influential book. It won the National Book Award for poetry in 1960. I read it in 1962 and I hated it. In a shallow way, my dislike was a matter of social class. I said aloud to Lowell’s book, “Yeah, I had a grandfather, too.” Like my fellow would-be urban Beatniks at Rutgers, I preferred the manners of Allen Ginsberg’s “Kaddish”—the poet reading the Hebrew prayer for the dead while listening to Ray Charles and walking the streets of Greenwich Village.

A year later, when I arrived as a graduate student at Stanford, I entered a culture more bucolic than what I had known at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey—the home state of Ginsberg, with urban New Brunswick about an hour from those Village streets. Surrounding the sleepy Palo Alto of those days, an actual village, the future Silicon Valley was still a place of horse ranches and apricot orchards. Leland and Jane Stanford had founded the university on their ranch, in 1891, and the school’s affectionate nickname for itself was “the Farm.” In Palo Alto, too, as in the quite different literary and urban terrain of Rutgers, Robert Lowell’s poetry was not held in the first rank of importance.

But five or six years later, in 1970, I took a job teaching at Wellesley College, not far from Boston and Cambridge, where I met poets who considered Life Studies a major work of art.

More here.

Reflections on an Essay by Eugene Wigner

Sergiu Klainerman in Inference Review:

IN THE SPRING of 1960, Eugene Wigner delivered a lecture at New York University. Published as an essay the following year under the title “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences,”1 Wigner’s remarks sparked a debate that continues to the present day. Indeed, the significance and implications of the essay have been discussed far beyond the realms of mathematics and physics.

IN THE SPRING of 1960, Eugene Wigner delivered a lecture at New York University. Published as an essay the following year under the title “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences,”1 Wigner’s remarks sparked a debate that continues to the present day. Indeed, the significance and implications of the essay have been discussed far beyond the realms of mathematics and physics.

Wigner’s essay has long been a source of fascination for me. I was a graduate student when I first read the essay and I have returned to it many times over the intervening years. Although I have often found myself admiring the clarity and articulation of Wigner’s observations, it is the mystery he pointed to that first caught my imagination and is at the heart of its enduring appeal.

The mystery Wigner described can be stated as follows: mathematical concepts introduced for solving specific problems turn out to have unexpected and mysterious consequences in seemingly unrelated areas.

More here.

Hyperthymia, rationality, and emotional self-regulation

Andrew Van Wagner interviews Ronald de Sousa, a philosopher best known for his work in philosophy of emotion, in his Substack newsletter:

1) What are the most exciting projects that you’re currently working on? And the most exciting projects that you know of that others are working on?

1) What are the most exciting projects that you’re currently working on? And the most exciting projects that you know of that others are working on?

I’m working on a project about how language affects our emotions. For this project, I’m basing my general perspective on the “dual processing” hypothesis—that there are two systems, one intuitive and one analytic—that was popularized in Daniel Kahneman’s very famous and wonderful 2011 book Thinking, Fast and Slow. I’m interested in how this dual system affects our emotions, which then translates into the question of how our emotions are elaborated when we talk about them—someone who values rationality might think that the analytic system should be trusted over the intuitive one, but our brains can only do a very limited amount of conscious reasoning, which means that you essentially have to rely on the intuitive system for the most part.

I’m also writing a book—Why It’s Okay to Be Amoral—that’s based on a 2021 article that I wrote about morality. I argue in the book that philosophers are basically wasting their time in trying to justify the principles that they peddle as fundamental moral principles—my view is that such efforts are useless when people have different moral foundations and each one is at the very rock bottom of understanding and explanation, which makes rational discourse impossible.

More here.

There are many good reasons to take care of your hearing — from the sound of birds chirping to being able to carry on a conversation in a restaurant. But the best reason to take care of your hearing is to take care of your brain. Hearing loss in middle age — ages 45 to 65 — is the most significant risk factor for dementia, accounting for more than 8 percent of all dementia cases, Richard Sima reports in this week’s

There are many good reasons to take care of your hearing — from the sound of birds chirping to being able to carry on a conversation in a restaurant. But the best reason to take care of your hearing is to take care of your brain. Hearing loss in middle age — ages 45 to 65 — is the most significant risk factor for dementia, accounting for more than 8 percent of all dementia cases, Richard Sima reports in this week’s  I am a recovering perfectionist.

I am a recovering perfectionist.