Jef Akst in The Scientist:

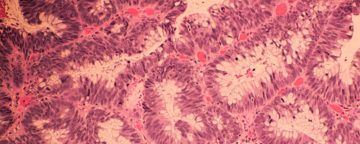

Most models of how tumors evolve have assumed that the process is based predominately on cancer cells’ genetics, and many cancer treatments are specifically targeted to mutations associated with disease. But comparing whole genome sequence data with RNA-seq data from samples of colorectal tumors revealed that the vast majority of gene expression differences among cancer cells cannot be explained by genetics, researchers report in Nature today (October 26).

Most models of how tumors evolve have assumed that the process is based predominately on cancer cells’ genetics, and many cancer treatments are specifically targeted to mutations associated with disease. But comparing whole genome sequence data with RNA-seq data from samples of colorectal tumors revealed that the vast majority of gene expression differences among cancer cells cannot be explained by genetics, researchers report in Nature today (October 26).

“So far, a lot of the work that’s been done exploring cancer evolution in cancer development has focused very much on just the genetics,” says Nicholas McGranahan, a computational cancer researcher at the University College London Cancer Institute’s CRUK UCL Centre who was not involved in the research. But according to the new study, “there’s lots of these alterations that they can’t identify a clear [genetic] underpinning for. . . . It’s a nice study because it highlights some of the limitations of what we’ve been doing before.”

Computational biologist Andrea Sottoriva says that it’s those limitations that led him and his colleagues to consider the transcriptome in cancer evolution. “Basically, looking at the genetic evidence was not explaining everything that we were seeing,” says Sottoriva, a group leader at the Institute of Cancer Research, London, and the head of Computational Biology Research Centre at Human Technopole in Milan, Italy. For example, he explains, “if you just look at . . . mutations in genes that are involved in cancer, it’s not very easy to distinguish a benign cancer from a malignant cancer: In a benign cancer, there are as many cancer driver mutations as in a malignant cancer.”

More here.

Taylor Swift was quite the romantic when she burst on the scene in 2006. She sang about the ecstasies of young love and the heartbreak of it. But her mood has hardened as her star has risen. Her excellent new album, Midnights, plays upon a string of negative emotions — anxiety, restlessness, exhaustion and occasionally anger. “I don’t dress for women,” she sings at one point, “I don’t dress for men/Lately I’ve been dressing for revenge.”

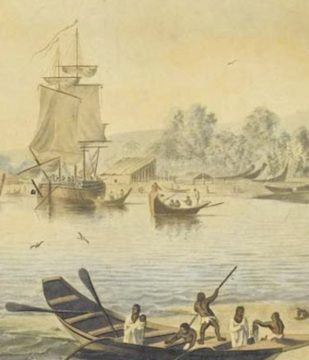

Taylor Swift was quite the romantic when she burst on the scene in 2006. She sang about the ecstasies of young love and the heartbreak of it. But her mood has hardened as her star has risen. Her excellent new album, Midnights, plays upon a string of negative emotions — anxiety, restlessness, exhaustion and occasionally anger. “I don’t dress for women,” she sings at one point, “I don’t dress for men/Lately I’ve been dressing for revenge.” The first Europeans to reach Tahiti were the crew of HMS Dolphin, commanded by Samuel Wallis, in June 1767. When the Dolphin approached the island and, like the Beagle, anchored in Matavai Bay, some Tahitians had thought the ship was “a floating island.” Others had recalled a prophecy that, as a result of the chopping down of a sacred tree, newcomers of an unknown kind would arrive and that “this land would be taken by them. The old order will be destroyed and sacred birds of the land and the sea will come and lament what the lopped tree has to dictate. [The newcomers] are coming upon a canoe without an outrigger.”

The first Europeans to reach Tahiti were the crew of HMS Dolphin, commanded by Samuel Wallis, in June 1767. When the Dolphin approached the island and, like the Beagle, anchored in Matavai Bay, some Tahitians had thought the ship was “a floating island.” Others had recalled a prophecy that, as a result of the chopping down of a sacred tree, newcomers of an unknown kind would arrive and that “this land would be taken by them. The old order will be destroyed and sacred birds of the land and the sea will come and lament what the lopped tree has to dictate. [The newcomers] are coming upon a canoe without an outrigger.” Studying quantum mechanics, which I’ve been doing

Studying quantum mechanics, which I’ve been doing  The politics of inflation in 2022 are surprising.

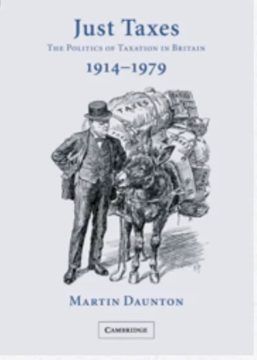

The politics of inflation in 2022 are surprising. Much has been written about

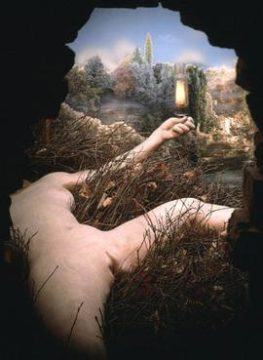

Much has been written about  One bleary morning in a darkened art history classroom—think Modernism 101—a slide of the interior of Étant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau / 2° le gaz d’éclairage (1946-1966) flashed by. Its glimmering afterimage remained in my mind’s eye long after. One might say it never really left. I still remember how rattled I was as I tried to make sense of it. The odd installation didn’t fit into what was being taught as modern art at the time, yet conversely—perversely—it nominally coincided with enough of what art history syllabi then encompassed: female nudity mediated by a male gaze, corporeality framed by idyllic landscapes. What perhaps shook me most, however, was that it didn’t tally at all with what I was just learning about the art of its maker. Duchamp, the painter turned cool conceptualist. Duchamp, father of the readymade and chess-playing lover of puns. Duchamp, the sometime art dealer, occasional crossdresser, and elegant prankster who had definitively “retired” by the 1930s. Even if these myriad “Duchamps”already indicated a great flexibility regarding the concept of art and artist, it was Etant donnés, I thought, that didn’t fit. And I was not alone in thinking so.

One bleary morning in a darkened art history classroom—think Modernism 101—a slide of the interior of Étant donnés: 1° la chute d’eau / 2° le gaz d’éclairage (1946-1966) flashed by. Its glimmering afterimage remained in my mind’s eye long after. One might say it never really left. I still remember how rattled I was as I tried to make sense of it. The odd installation didn’t fit into what was being taught as modern art at the time, yet conversely—perversely—it nominally coincided with enough of what art history syllabi then encompassed: female nudity mediated by a male gaze, corporeality framed by idyllic landscapes. What perhaps shook me most, however, was that it didn’t tally at all with what I was just learning about the art of its maker. Duchamp, the painter turned cool conceptualist. Duchamp, father of the readymade and chess-playing lover of puns. Duchamp, the sometime art dealer, occasional crossdresser, and elegant prankster who had definitively “retired” by the 1930s. Even if these myriad “Duchamps”already indicated a great flexibility regarding the concept of art and artist, it was Etant donnés, I thought, that didn’t fit. And I was not alone in thinking so. In his

In his  On 12 September, Amgen announced that the latest trial of sotorasib found that it extended progression-free survival — a measure of the time elapsed without the cancer worsening — only by about one month longer than standard chemotherapy. Only 28% of the participants treated with sotorasib responded to it. That’s roughly twice the number who responded to the standard chemotherapy, but a sign nonetheless that most people who have KRAS-positive lung cancers will not be helped by the new drug.

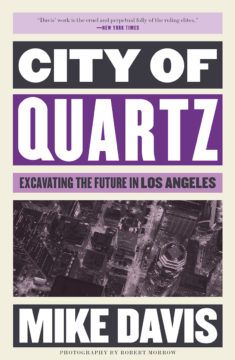

On 12 September, Amgen announced that the latest trial of sotorasib found that it extended progression-free survival — a measure of the time elapsed without the cancer worsening — only by about one month longer than standard chemotherapy. Only 28% of the participants treated with sotorasib responded to it. That’s roughly twice the number who responded to the standard chemotherapy, but a sign nonetheless that most people who have KRAS-positive lung cancers will not be helped by the new drug. Mike Davis, author and activist, radical hero and family man, died October 25 after a long struggle with esophageal cancer; he was 76. He’s best known for his 1990 book about Los Angeles, City of Quartz. Marshall Berman, reviewing it for The Nation,

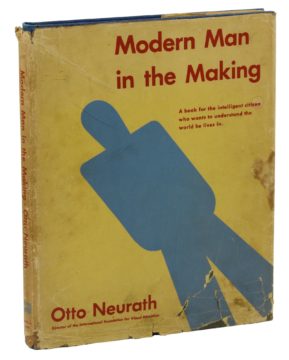

Mike Davis, author and activist, radical hero and family man, died October 25 after a long struggle with esophageal cancer; he was 76. He’s best known for his 1990 book about Los Angeles, City of Quartz. Marshall Berman, reviewing it for The Nation,  In 1939, the Viennese economist and sociologist Otto Neurath (1882–1945) released Modern Man in the Making to an American public. Published by Alfred A. Knopf, Neurath’s pictorial statistical history of human technological adaptation and social cooperation addressed a modern audience searching for optimistic narratives amid an economically, politically, and socially volatile era. If not actual members of the managerial class, readers of Neurath’s book were immersed in a “culture of management” that permeated many aspects of modern life. The concerns of the broader public were addressed by managerial commitments to profitable business and social betterment through the promotion of efficiency during the interwar years. Between 1917 and 1939 Neurath frequently referenced Scientific Management and its program for promoting cooperation through efficiency. Abandoning theology and enlightenment liberalism, he even went so far as to propose an ethics modeled on an extrapolation of Scientific Management which would take the form of the extension of convention and habit into new forms of life.

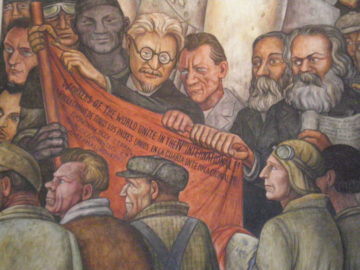

In 1939, the Viennese economist and sociologist Otto Neurath (1882–1945) released Modern Man in the Making to an American public. Published by Alfred A. Knopf, Neurath’s pictorial statistical history of human technological adaptation and social cooperation addressed a modern audience searching for optimistic narratives amid an economically, politically, and socially volatile era. If not actual members of the managerial class, readers of Neurath’s book were immersed in a “culture of management” that permeated many aspects of modern life. The concerns of the broader public were addressed by managerial commitments to profitable business and social betterment through the promotion of efficiency during the interwar years. Between 1917 and 1939 Neurath frequently referenced Scientific Management and its program for promoting cooperation through efficiency. Abandoning theology and enlightenment liberalism, he even went so far as to propose an ethics modeled on an extrapolation of Scientific Management which would take the form of the extension of convention and habit into new forms of life. Diego Rivera painted

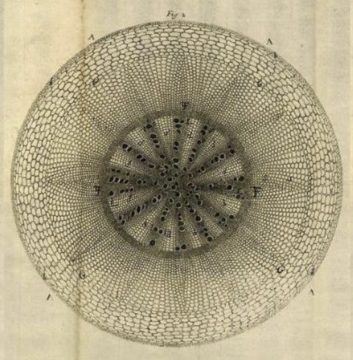

Diego Rivera painted  Modern genetics was launched by the practice of agriculture: the Moravian monk Gregor Mendel discovered genes by cross-pollinating peas with a paintbrush in his monastery garden in Brno. The Russian geneticist Nikolai Vavilov was inspired by crop selection. Even the English naturalist Charles Darwin had noted the extreme changes in animal forms created by selective breeding. Cell biology, too, was instigated by an unassuming, practical technology. Highbrow science was born from lowbrow tinkering.

Modern genetics was launched by the practice of agriculture: the Moravian monk Gregor Mendel discovered genes by cross-pollinating peas with a paintbrush in his monastery garden in Brno. The Russian geneticist Nikolai Vavilov was inspired by crop selection. Even the English naturalist Charles Darwin had noted the extreme changes in animal forms created by selective breeding. Cell biology, too, was instigated by an unassuming, practical technology. Highbrow science was born from lowbrow tinkering. In his classic book from 1990, Three Rival Versions of Moral Inquiry, the Marxist-turned-Catholic-Thomist philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre discusses three basic modern and postmodern approaches to philosophical inquiry: encyclopedia, genealogy, and tradition. The genealogical method, pioneered by Friedrich Nietzsche and elaborated by Michel Foucault, presents a historical narrative in which ideas develop and grow over time. According to this thinking, being and truth are conditioned by history (historicized) and thus develop in tandem with the twists and turns of science, technology, economics, language, and culture.

In his classic book from 1990, Three Rival Versions of Moral Inquiry, the Marxist-turned-Catholic-Thomist philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre discusses three basic modern and postmodern approaches to philosophical inquiry: encyclopedia, genealogy, and tradition. The genealogical method, pioneered by Friedrich Nietzsche and elaborated by Michel Foucault, presents a historical narrative in which ideas develop and grow over time. According to this thinking, being and truth are conditioned by history (historicized) and thus develop in tandem with the twists and turns of science, technology, economics, language, and culture.